The Gaze of Revolt:

Chen Chieh-Jen's historical images and his aesthetic of horror

¡@

CULTURAL DILEMMAS DURING TRANSITIONS

15-17 OCTOBER 2000

WARSAW

¡@

Joyce C.H. Liu major-works.htm

Graduate Institute of Comparative Literature, Fu Jen University, Taiwan

¡@

¡@

There looms, within abjection, one of those violent, dark revolts of being, directed against a threat that seems to emanate from an exorbitant outside or inside, ejected beyond the scope of the possible, the tolerable, the thinkable.

---Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror (1)

History has been lingchi-ed, that is, chopped and severed as human bodies. Violence is also gradually internalized, institutionalized and hidden. We do not see where we are and what was before us. We do not see the violence of history or that of the State either. That is the reason why we need to gaze at the images of horror and penetrate through them. Is the dark abyss of wounds not the very crack that we need to pass through so as to arrive at the state of full-realization and self-abandonment?---Chen Chieh-Jen, About the Forms of My Works

¡@

1. Introduction: the cultural transition and the artistic response

Taiwan has witnessed rapid and drastic political changes and cultural transitions in recent decades. The isolation of Taiwan¡¦s international political status [1], the open confrontation between the Kuomintang government and the ¡§dang-wai¡¨ (outside of the party) members in the Kaohsiung Incident in 1979 [2], the lifting of Martial Law in 1987, the first democratic legislative election in 1992, the first presidential election in 1996, and the turning over from the KMT government to the DPP government in 2000: all are significant events that marked the stages of political as well as cultural transformation in Taiwan. Along with such process of transformation, there emerged massive movements of critical questionings and re-constructions of Taiwanese identities, a shift from the mainland-centered cultural identity to the demand for the local consciousness, from a Chinese to a Taiwanese. Thomas Gold has rightly observed that, ¡§a quest for a unique Taiwan identity began in the mid-1970¡¦s and gathered steam with Taiwan's increased diplomatic isolation and the rise of the tangwai¡¨ (61); in 1990's, after the lifting of the Martial Law, ¡§defining Taiwanese identity is still a process at the stage of rediscovering a history comprised of a diverse array of components, but it has become a conscious project¡¨ (64). Such identity construction discourse shaped itself in all cultural forms in Taiwan, including public debates, political campaigns, scholarship, drama, dance, literature, film, and naturally also visual arts.

How do the visual artists in Taiwan respond to such changes and the urgent need to reassure Taiwanese cultural identities? Compared to the more radical reactions exercised by other forms of cultural representation starting from the 1970s [3], the debates among Taiwanese art critics on ¡§the local¡¨ and ¡§the western¡¨ during 1991 to 1993 appeared belated and déjà-vu [4]. Throughout the debates, the modernist and post-modern arts, such as abstractionism, abstract expressionism, surrealism, new-expressionism, super-realism, installation art, and so on, were all criticized as ¡§rootless,¡¨ ¡§lack of subjectivity¡¨, and with ¡§no sense of history and reality.¡¨[5] The 1996 Taipei Biennial: The Quest for Identity and the 2-28 Commemorative Exhibitions from 1996 to 1999 are typical examples in the wave of the reinforced demand for identity construction in the post-Martial Law era.

The recurrence of the ¡§Western versus Local¡¨ debates in the arena of the visual arts draws my attention to the questions of the locatability of the subject in the art work as well as the effectiveness of the visual sign for the ¡§local¡¨ or the ¡§sense of history.¡¨ These are the questions that I want to discuss in this paper. I want to discuss first about the cultural iconography that the contemporary Taiwanese artists attempted to shape, as seen in the series of the 2-28 Commemorative Exhibitions, held by Taipei Fine Arts Museum. I would then like to focus on the images of horror that Chen Chieh-jen, one contemporary artist who was invited in the 2-28 Commemorative Exhibition in 1998, presented in his Revolt in the Soul and Body series.

For me, the study of these visual representations of cultural past offers us a dimension of understanding that is rather complex. We are here dealing with the history of mentalities, as suggested by Jacques le Goff, for example, the mode of thinking, internalized structure of punishment, and the plurality of subjectivity and identity, which may not be recorded in written words. Visual images, and the codes that art operates, Jacques le Goff has pointed out, could be independent to its historical environment. We need to go into ¡§certain local systems¡¨ in order to analyze ¡§the structure and evolution of mentalities¡¨ (¡§Mentalities: a history of ambiguity,¡¨ 174).

In analyzing and interpreting the visual images presented in the series of the 2-28 Commemorative Exhibitions, we will realize that these images largely speak of the impulses that are parallel to the complex dynamics of the concurrent society. Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s magical-realist photographic images and his aesthetic of horror, though drastically different from the other realist and narratorial works related to historical themes, offer an unique interpretations of the subjective and historical experience of Taiwanese. Chen does not present any chronological explanations for the state of current affairs or any statement of clear-cut identity or subjectivity. Rather, he questions our knowledge with the visible reality and our understanding of identity as well as subjectivity. The negative mode of presentation in Chen Chieh-jen¡¦s works, and the images of the ugly, works on a certain mode of the gaze, a gaze of revolt, a revolt not in physical transgression of the law, but in its critical questioning and reversing our perception. This gaze of revolt indicates the emergence of a ¡§culture of revolt,¡¨ as discussed by Julia Kristeva in her recent book The Sense and Non-Sense of Revolt.

For Kristeva, the ¡§culture of revolt¡¨ has the ability to resist the normalizing powers of regulation and punishment. This regulation, though neither totalitarianism nor fascism, represents the invisible power surrounding us, from fundamentalism, nationalism, to nonpunitive legislation, delaying tactics, media theatricalization, and so on. (The Sense and Nonsense of Revolt 4-9) Kristeva continues to explain her use of ¡§revolt¡¨ that it is not in the sense of transgression but to describe the process of the analysand¡¦s retrieving his memory and beginning his work of anamnesis with the analyst.¡¨ In anamnesis, and in literature and art, Kristeva suggests, the subject/artist retrieves his memories of the trauma, worked through and worked out his problems, through repetition and free association in transference, revealed the artistic experience of human subject and the subject¡¦s psychical space is thus renewed (28).

To me, Chen¡¦s gaze of revolt, a critical questioning of the normalizing mode of the gaze, takes us to look into the various displacement in the scenes of the trauma, and the hidden violence and cruelty of history behind it. We realize that in the visual configurations of the magical-realist moments inscribed the unspoken cultural memories and histories, not only of the most recent scenes of collective trauma in Taiwan, but also of the ones repeated in Chinese history.

¡@

2. The February Twenty-Eighth Incident Commemorative Exhibitions: the constructions of cultural iconography

2.1 The 2-28 Commemorative Exhibitions

Let us first take a look of the series of the 2-28 commemorative exhibitions of the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, and see how contemporary Taiwanese artists present one of the most tragic events in Taiwan history. Chen Shuibian, then the mayor of Taipei City, first initiated this series of annual exhibitions in 1996. These four exhibitions, I think, present an emblematic performance of the collective impulse to readjust people¡¦s position to Taiwan history.

The February 28th Incident of 1947 [6] caused the death of thousands of civilians, ranging from 18000 to 28000 according to different reports, mostly local leaders, particularly lawyers, doctors, scholars and students. These leaders helped the people to protest against the corrupt government that took over Taiwan after the end of World War II when it retreated from China. The arrest of a woman who sold cigarette without a license on February 28th of 1947 incited the anger of the people and the public protests soon rose up out of control. Chiang Kai-shek¡¦s troops arrived shortly and started forced suppression and massive execution throughout the island. Countless people were murdered, and many others kept in prison till the beginning of 1980s. The February 28th Incident was the beginning of the long White Terror period and the Martial Law, which started in 1950 and ended in 1987. For over forty years, this historical tragedy had been silenced, as if effaced from history and people¡¦s consciousness. It was not until 1987, a few months before the government announced the dropping of the Martial Law, when a local group ¡§2-28 Peace Promotion Association¡¨ moved its petition for the government to reveal the historical facts of the February 28th Incident. In 1991, the official report on the February 28th Incident was finally published, and it was followed by hundreds of books, oral histories and conferences on the same historical event in the following years.

Taipei Fine Arts Museum¡¦s 2-28 Commemorative Exhibition in 1996, Remembrance and Reflection, was literally the ¡§first¡¨ collective and official act to extend people¡¦s reflections on the traumatic event through artistic form. [7] According to Lin Mun-Lee, the director of Taipei Fine Arts Museum, the first exhibition in 1996 focused on memorializing the 2-28 Incident and showed ¡§pieces both directly and indirectly related to the incident, including essays and photographs¡¨ and thus contained ¡§educational and historical significance¡¨ (Lin Mun-Lee 1998, 7). The theme of the second exhibition was designed as ¡§Sadness Transformed¡¨ and indicated the purpose to transcend beyond the historical trauma. Apparently this ¡§sublimation¡¨ could not feed people¡¦s expectation and was thus criticized extendedly. Hsiao Chong-Ray, a contemporary scholar of art history, remarked with discontent that ¡§some internationally renown artist even presented his old abstract water ink piece and claimed that it fits the theme of sublimation¡¨ (Hsiao Chong-Ray 14). Chen Shui-bian, still the Taipei City mayor, also stressed specifically that the exhibition in 1998, Reflection and Reconsideration, has to ¡§bring the artists¡¦ work back around to the actual event, to demand that the artists look closely at the event and enter into the historical circumstances surrounding it¡¨ (Chen Shui-bian 5). Hsiao Chong-Ray, the curator of the 1998 exhibition, invited twenty-six artists of the ¡§post 2-28 generation,¡¨ those who were born after 1947, who did not experience this tragic event themselves but were mature and bold enough at this time to investigate this historical tragedy retrospectively and critically (Hsiao Chong-Ray 15). Though the designs of the posters of the previous three exhibitions indicated the tendency to move to a more reflexive and abstract representation of the traumatic scene, the proclaimed purpose of the 1998 exhibition was still to ¡§bring the focus of these pieces back to the incident itself¡¨ (Lin Mun-Lee 1998, 7).

¡@

In the following year, the director Lin Man-Lee and the curator Vince Shih both stressed once again to come even closer to the historical event, to ¡§recreate historical sites and images,¡¨ basing on the narratives of 30 historical scenes selected and arranged chronologically by Vince Shih, with the hope that the exhibition could ¡§enter and understand history¡¨ (Shih 10-20; Lin 1999, 7).

2.2 The narratorial and historical impulse

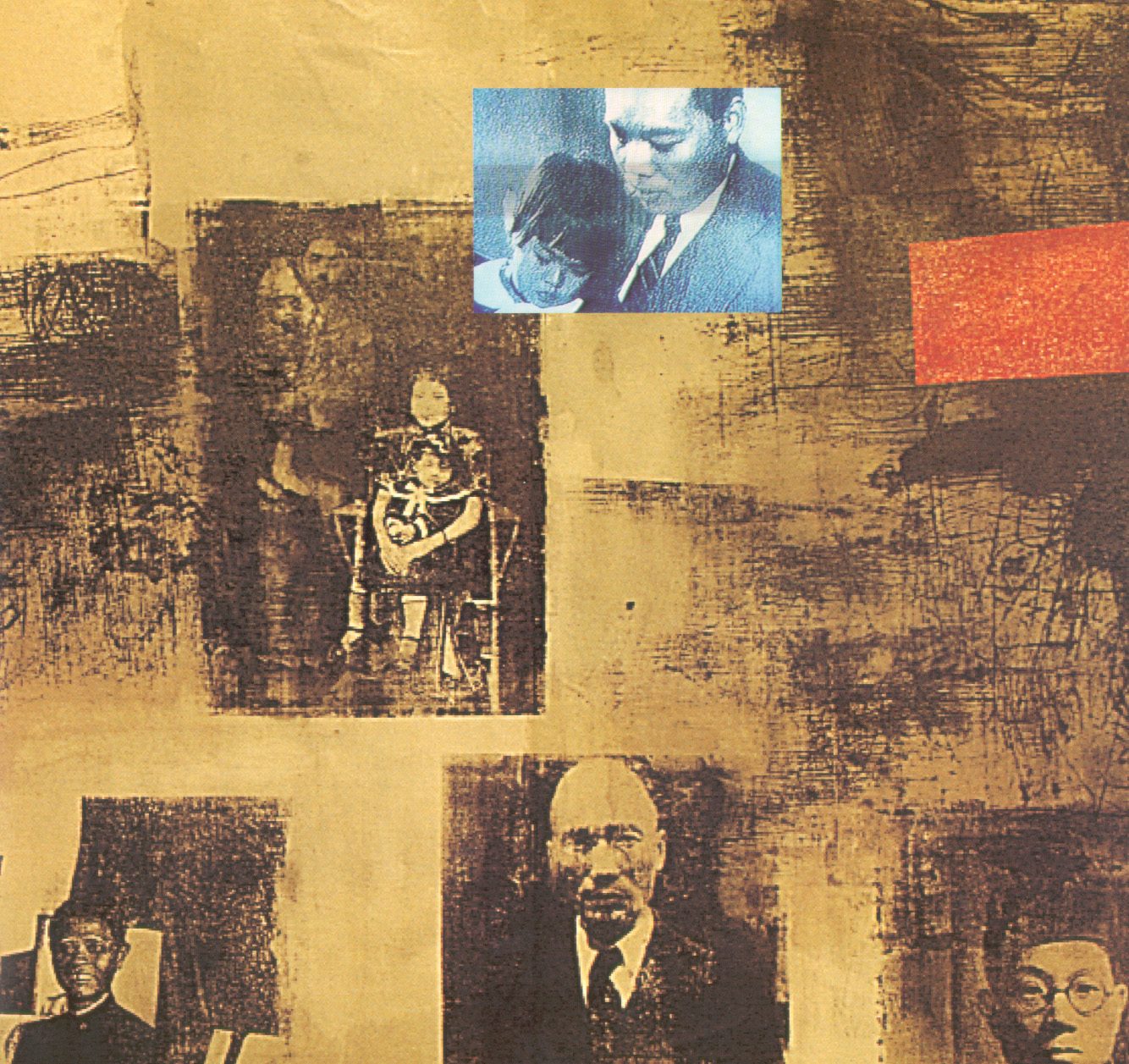

The intention to construct an appropriate cultural iconography through returning to and narrating the traumatic history is manifest in these exhibitions.[8] Therefore, even though local scholars and art critics curate the 2-28 exhibitions in 1998 and 1999, unlike the previous two exhibitions that were designed by the officials, we see the same impulses in the art works to narrate historical scenes. For example, in Changing Cloud by Chou Meng-Te (1953-), we see the street scene in which the military troops were arresting the people in revolt. In Appeal for Justice and Take Revenge by Kuo Bor-Jou (1960-), we see the installation with mixed media, including old photographs and video images recounting the tragic event.

¡@

Such clear narratorial or accusational purpose also is present in the 1999 exhibition. For example, in Landing at Keelung by Su Hsin-tien (1940-), we see the remapping of the climatic moment in which the armed KMT troops landed at Keelung and started the bloody massacre. In False Promises by Vince Shih (1947-) the curator¡¦s own work, we see the installation with distorted KMT party icon and the red cloth hanging on the wall, inscribed with the military commander Chen Yi¡¦s official announcement through radio, and another red cloth covering a mold of Taiwan island, surrounded by an array of butcher¡¦s knifes on the chopping boards.

¡@

The subject position these artists take is apparent in these works. The narratorial motives, allegorical meanings and the historical referential elements are clearly stated in these artistic representations. There seems to be a clear cause-effect explanation and logical follow-up actions or attitudes the artists want the audience to take after viewing these artistic representations.

The reason that I want to point out the emblematic and performative aspects of the four 2-28 exhibitions is because, from the anxiety to move ever closer toward the actual historical event in each exhibition, we see parallel impulse in contemporary Taiwanese society. Being erased from history and public discourse for over forty years, the 2-28 Incident turns out to be the primal scene of the historical trauma in the collective memories, the moment in which the separated mother-country arrived, opened her arms, and revealed her ferocious and blood-thirsty face, and executed the scene of castration. To speak of it and to look at it is the first act to acknowledge the traumatic moment, the repressed, the damaged, and to re-claim the people¡¦s subjectivity. But, sticking to the visualized scene of the historical moment is to fetishized the image while avoiding the reality behind the scene.

2.3 The magical-realist presentation of historical reality by Chen Chieh-Jen

Contrasting to the above-mentioned pieces, Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s A Picture of Rebellion 1947-1998, exhibited in the 2-28 Commemorative Exhibition in 1998, along with other artists of ¡§post-2-28 generation¡¨, stands out as the most unsettling one to me. The unsettling power, I think, lies in the ambiguity of the position the artist takes in relation to the historical traumatic moment.

In this installation, the artist arranged a huge computerized photographic image in the center of the hall, and four stone tablets hanging on the walls, with muffled whispering human voices behind the screen, as if the audience is to be situated in front of a hell-like historical scene. But when we come closer to the screen and observe the photographic image, we¡¦ll soon realize that it is a phantasmatic presentation not of the massacre scene but rather of the perverse state of mind of the sadistic torturers, because we are faced with a carnivalesque play of sado-masochistic self-destruction.

¡@

¡@

Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s treatment of the ¡§photographic image¡¨ is a sharp contrast to Kuo Bor-jou¡¦s usage of the old historical photographs in his Appeal. Kuo clearly intended to present the objective reportage function of the old photographs. Viewing old photographs, with faded images on them, the audience seems to be brought back to the spots of time framed in the photographs. Chen Chieh-Jen also gave us ¡§old photographs,¡¨ but he did not provide us the narrative. Rather, he presented in front of us the vision of horror. The image tells us not the historical moment of the visible scene, but of the hidden states of human mind in the scene of violence. Therefore, from the absurd and perversely hilarious expression on the faces of the figures in the photographs, the artist himself as the model, we actually read the artist¡¦s interpretation of the historical ¡§truth,¡¨ or certain forms of the extreme states of violence that we face repeatedly in history.

¡@

3. Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s Historical Images: the revolt of the gaze

3.1 Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s project

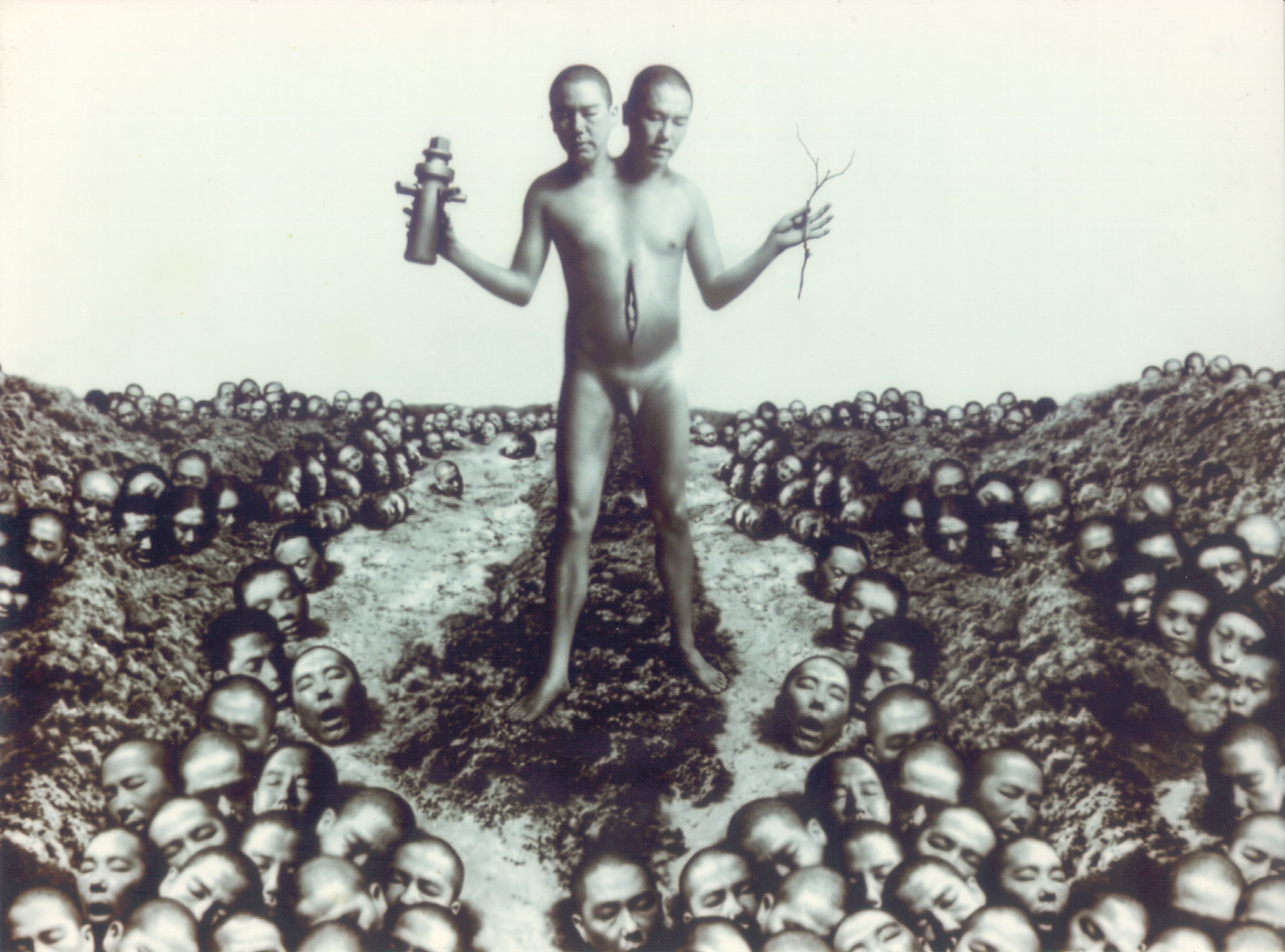

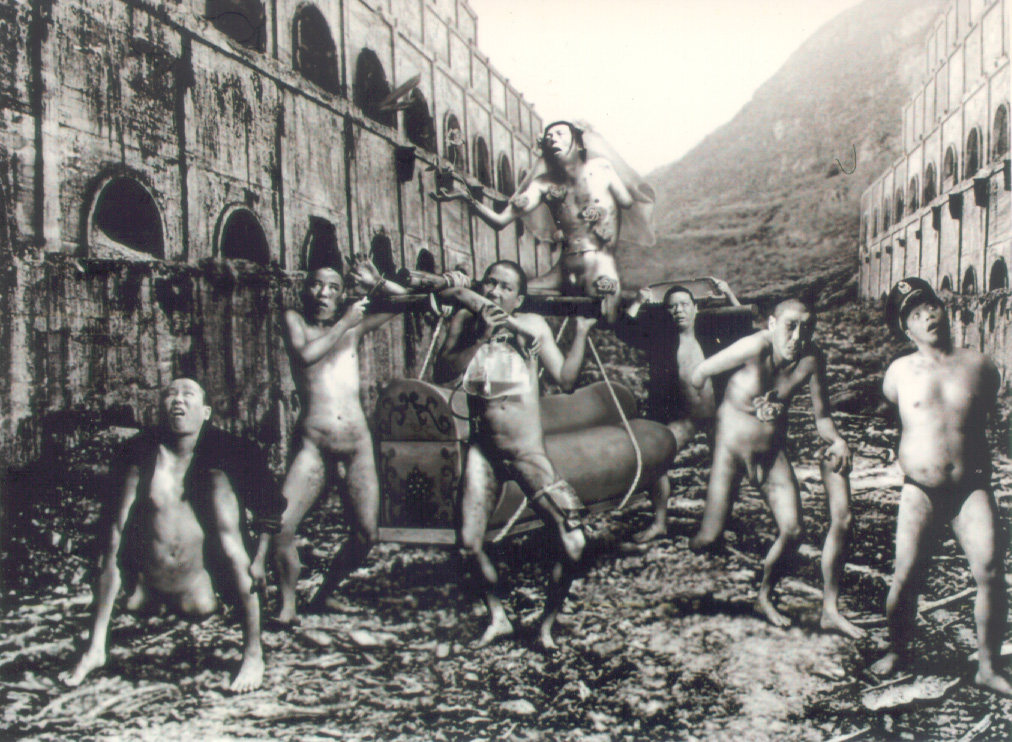

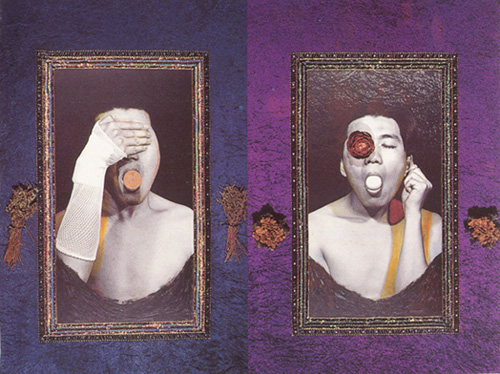

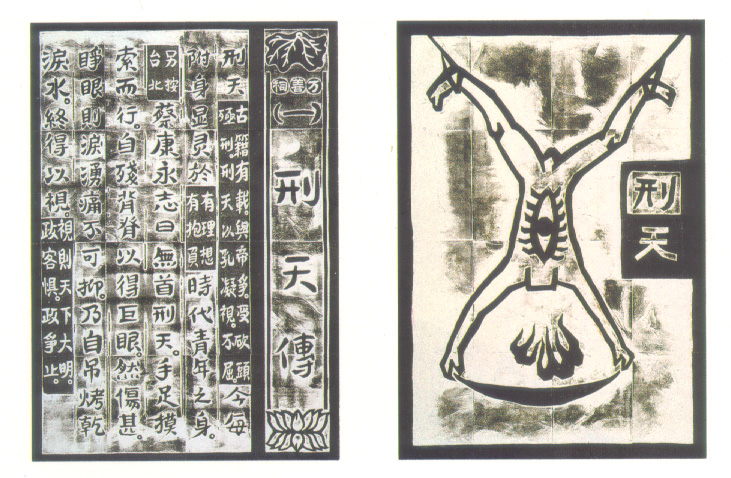

Chen Chieh-Jen was born in 1960 in Taiwan. His exhibition in TFAM in 1998, A Picture of Rebellion 1947-1998, is one of the series Revolt in the Soul and Body that he has been working on since 1996. [9] We can divide his works into two groups: the ones quoting and appropriating historical photographs, including Genealogy of Self (1996), Being Castrated (1996), Self-Destruction (1996), Rule of Law series (1997), Lost Voice series (1997), and the ones composed according to the artist¡¦s phantasm, including Image of An Absent Mind (1998), The Image of Identical Twins (1998), Na-Cha¡¦s Body (1998), and A Way Going to An Insane City (1999).

In one interview, [10] Chen Chieh-Jen explains that the purposes of his project of Revolt in the Soul and Body are two folds: the first half of the series is to present the historical photographs taken from 1900 till 1950, from the beginning of the modern era, the date chosen arbitrarily by the artist, till the year in which the Martial Law was erected in Taiwan, and the second half is to present entirely fictional visions. Through these two sets of photographic images, Chen Chieh-Jen intended to present the cycle of violence and brutality, the rotation from the role of the tortured to that of the torturer, and the path of violence from the external act to the internalized and institutionalized malice, and from the witnessed scenes of brutality to the imagined site of madness.

Let us look into some of his works and discuss his interpretation of such history of violence and horror. Genealogy of Self, Being Castrated, Self-Destruction, Rule of Law, and Lost Voice belong to his historical photographic images. In these photographic images, though each basing on certain historical event and documentary photographs, the historical and documentary truth is drastically challenged, and the modifications clearly indicate the artist¡¦s play of the gaze.

3.2 Chen¡¦s play on the gaze of history

Looking at the pictures, our gaze first falls on the wounds on the tortured bodies, and then quickly shifts to the surrounding details as if to avoid the fascinating but terrifying gaps on the bodies. We notice the internal gazes presented in the pictorial space as well as the facial expressions and the physical gestures of the figures. We also see the irony in the historical moments, including the apparatus employed, when the original pictures were taken. The audience in Genealogy of Self, for example, apparently was all attracted by the act of the torture and they all turn their gaze upon the executioner¡¦s move, participating the moment of the thrill. Genealogy of Self is based on the photograph used by Geroges Bataille in his Tears of Eros. [11] Chen Chieh-Jen placed himself in the left-hand side of the background as one of the on-lookers. This picture presents a scene in ¡§Linchi.¡¨[12]

The duplicated heads of the victim turn upward and gaze at the sky, dazed, perhaps in a delirious state affected by opium. This seemingly ecstatic and yet delirious state brings us to the ambiguous juncture of extreme horror and erotic ecstasy, as discussed by Georges Bataille. This historical moment was framed by the photographer, a Western anthropologist, and in this frame we see the West¡¦s gaze at the most exotic and primitive scene in Chinese culture. The clash between the Chinese and the West is crystallized in this dichotomy between the primitive cruelty versus the modern technology. The anthropological and even tourist curiosity of the West about the Chinese execution, les Supplices Chinois, is most explicitly expressed by the series of postcards on which the images of the Lingchi was recorded and which were circulated among westerners. [13]

Being Castrated, a continuity of the previous theme but also a crude contrast to it, presents a scene in which all figures lined up, except the victims, all posed in front of the camera, looked into the camera eye, and inviting the viewer¡¦s gaze. This picture is based on a photograph taken around 1904-1910, a scene in the street of Shanghai, the photographer unknown. Chen Chieh-Jen added two figures at both sides in the foreground, he himself as the model, suffering the penalty of castration, serving as a frame of the spectacular scene.

Chen Chieh-Jen seems to suggest that the gaze caught in the photograph, responding to the photographer¡¦s camera-gaze, a western instrument to record the moment of exoticism, serves as a mirror reflection of the historical moment in which the West showed its greatest interest in China. The castration condition, a signature by the artist on the image, indicates the historical condition of China in the early twentieth century during which the foreign concession was forced upon, and paradoxically China¡¦s modernization was launched. Moreover, this gesture of implicit invitation brings all those figures, the foreign ambassadors, the executioners, and the on-lookers up to the same position, the one in which all participate in this ritual, as collaborators. The castrated organs of the two artist/figures in the front gaze back at us, disrupting the circulation between the consumer¡¦s interests and the spectacular image.

The Rule of Law is based on a photo originally taken in the year after Wu-She Incident [14] in Taiwan, around 1931, the photographer unknown. Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s figure can be found as the Japanese commander, as one of the aboriginals on the left-hand side, and as the suffering figure at the center. In this picture, the hostility between the different tribes of the aboriginals, encouraged by the Japanese, is intensified by the contrast between the indifferent gaze of the head-hunters and the closed eyelids of the chopped-off heads of the Atayal. The Japanese commander holds out his gun-like penis in front of the lined-up chopped heads of the aboriginals, linking the human brutality to the erection of the phallic organ, the internal state of aggression. We notice that Chen¡¦s photographic interpretation of the historical moment, especially the intra-ethnic brutality, is moving toward the psychological significance behind the scene.

Likewise, Self Destruction also indicates the psychological aspect and the intra-ethnic malice in the scene of cruelty. The artist juxtaposed two historical photographs in this picture, the right-hand part of this picture using Jay Calvin Huston¡¦s photo taken in 1927 during the Qingdang period (purging the party), a scene in which Chiang Kai-shek¡¦s soldiers slaughtering the communists in Canton, and the left-hand part using a photo in around 1928 in the street of Shanghai, also a scene in the Qingdang period, the photographer unknown. The theme of the self-destructive violence is even more clearly exposed through the twin figures in the center, fiercely but happily killing each other. Again, Chen Chieh-Jen placed his images in the twin figure in the center, as the falling head in the foreground, and as one of the spectators in the background.

The trilogy of Lost Voice reaches at the pinnacle of the display of extreme horror. These pictures are based on a photo taken in 1946, during the Civil War period, when the Communist armies took Chongli, 90 miles northern to Zhang Jia Kou, and slaughtered the whole village. [15] The lumps of corpses appear already like a scene in hell. The ecstasy displayed on the face of the self-masturbating and auto-mutilating figures, Chen Chieh-Jen as the models, in transport of joy, dancing on the lumps of corpses, looking back at us, pushes the exasperating painful scene to the extreme.

We have to view these pictures as an epic, not of the heroes or victories, but of the fate of Chinese in the first half of the twentieth century. It is also an epic of the happenings of human psychic underneath the historical traumatic events. Through these historical photographic images, the histories of Chinese penalties and its residues, Chiang Kai-shek¡¦s slaughtering the communist members during the Qingdang period, the massacres between the Communists and the Kuomintang armies during the Civil War, [16] the Japanese¡¦ colonial domination and manipulation over the Taiwanese, and the intra-ethnic slaughterings among the Taiwanese aboriginals, all re-emerge in front of the audience, but in a very ambiguous and phantasmal mode. The play of the spectatorship and the perverse jouissance make the scenes much crueler than the original historical photo-texts originally intended to be. The recurrence of the double motif in all these pictures seems to further suggest Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s interpretation of the Chinese-Taiwanese condition, or the splitting of the human psyche. Moreover, Chen Chieh-Jen placed himself in all these pictures, in various roles, as signatures of different identities, and multiplies the ambiguity of the subject position in these acts of violence.

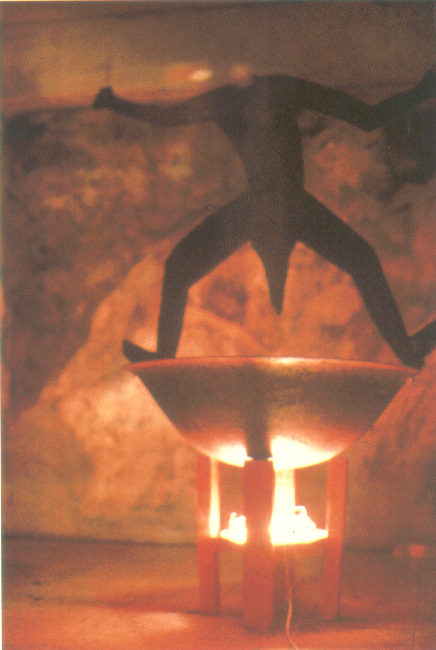

Moving from Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s historically based photographic images to the even more fantastic computerized-photographic images, the aftermath of the scene of violence, we seem to witness a bottomless descend from the furious ecstasy. Chen Chieh-Jen said that this group of pictures reflects the unseen and institutionalized violence during the Martial Law period. The allegorical references behind these images, be it the headless god of the wasteland era (Image of an Absent Mind), the juxtaposed moment of destruction and rebirth (The Image of Identical Twins), the institutional dominion over the juvenile prisoners (Na-Cha¡¦s Body), or the marriage/funeral procession toward the city of insane (A Way Going to an Insane City), to me, are not important. We see no more play of the gaze within the frame, but only blinded and mutilated figures. The ecstatic moment of execution and massacre is gone; what is left behind is the wasteland like condition, a condition of melancholy and despair.

¡@

¡@

3.3 A gaze at the obscene real

We could see the concept of hell and of human soul in Chinese folkloric belief working in Chen¡¦s artworks. He once said that he made use of the concept of the ¡§inferno¡¨ of Chinese folklore. In the inferno, there is a mirror, ¡§nie-jing,¡¨ the underworld judge would ask the dead to look into. The dead could see in the mirror his past behaviors and desires; nothing could escape from this reflection. He also said that he tried to explore the conditions of separate spirit egos, according to the Chinese Taoist understanding of human soul, simultaneously existing in one person. That is why he placed several ¡§I¡¨ in the frames of his photographic image. About history, Chen said, ¡§I tried to convey and present the suppressed and invisible image through my work . . . . The histories I am much concerned about are the histories excluded by the orthodox power, that is, the histories outside the history. Moreover, I¡¦m even more concerned about the histories survived in the realm of ecstasy, like the lacunae among the words, concealed in the midst of aphasia, infiltrated into our language, body, desire and smell¡¨ (¡§About the Form of My Works¡¨). Indeed, we see from these pictures the histories that have been silenced not only by the KMT government but also by our consciousness. We do not talk about the party purgation or the civil wars, nor the head-hunting of the aboriginals. Therefore, through looking into Chen¡¦s photographic images, we not only see the past memories and past lives in Chinese-Taiwanese histories flashing back, but also see something behind the scene, something related to our bodily memories. What bodily memories? It is a very difficult question to answer. We¡¦ll come back to this point later.

The questions Chen Chieh-Jen poses for us through his photographic images, either intentionally or unintentionally, can be phrased as follows. First, about the gaze: Who has the right to record or recount the past, with what instrument or apparatus? Who were looking at the pictures through the camera eye and dominated the power relations? How do we interpret the ambiguity in the relations between the gazing subject and the gazed object, between the photographer and the photographed, between the executioners/the on-lookers/the official-accomplice and the victim, and between the audience and the artwork? Another set of questions, about the revolt of the gaze, can also be raised: How do we read history? What has been hidden in our perception, or our narrative of the history? Can we resist the gaze determined by history and ideology? Can we uncover the surface of images and see the genealogy and the inherent connectedness not only within all the massacres in history but also within the institutionalized violence?

About the method of his production, Chen Chieh-Jen said,

I put these vague historical photographic images into computer, and enlarged them on a very large scale. On the screen these enlarged images seemed like the historical vestige scattered in the mist. Uncertain number of indistinct images, some vague faces, some pieces of dismembered bodies, some broken traces, with floating scents drifting in the mist. Who were they? When I intrude myself into the boundless space of image-specters, and tried to paint their faces according to my imagination, every stroke of my pen seemed to betray their original faces. These faces that I have painted seemed more like the masks, bearing the brand of my own face, the face of the Other. But, who is the real Other? As I painted the historical images, I also fused my body image and my body memories into the mist of images. (¡§About the Forms of My Works¡¨) [17]

¡@

Chen Chieh-Jen also said that he wanted to ¡§gaze¡¨ (ningshi) into the images so that he could ¡§penetrate¡¨ them:

I could not help but gazing at these photographic images of anonymous people being tortured and executed. It seemed that behind these images you could uncover another layer of image and unspoken hidden words. It seemed that there was another face emerging from each of the vague, faint faces, another shaking, unfixed body emerging from and overlapping on the fixed body . . .. As I gazed at these historical photographic images, I found that the past looked back on me . . .. (¡§About the Forms of My Works¡¨)

¡@

The ¡§gaze¡¨ Chen Chieh-Jen tries to explain is apparently not the ¡§gaze¡¨ in which, according to Norman Bryson, the vanishing point in the Albertian space gazes back and determined the spectator¡¦s position of viewing, not only in terms of perspective, but also in terms of ideology (¡§The Gaze and the Glance¡¨ 102-11). It is neither the Lacanian gaze with which the image-screen, inscribed with the code of the symbolic, hints at the viewer¡¦s lack. [18] That is, Chen¡¦s images are not the fetishized phallus, Objet Petit a, which screens away the real scene of trauma. His images are the displacement of the trauma. The artist intentionally presents in front of us, through horrifying and ugly images of reality, the real that escapes us in our daily life.

Pinpointing the historical references or the ¡§local systems¡¨ of folk beliefs that function in Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s construction of images could help us understand part of his images, but not all. This hidden reality he presented in front of us is apparently not only the history that has been erased by the government or the hell-like conditions of political strife. Why does Chen Chieh-Jen say that the histories are survived ¡§in the realm of ecstasy,¡¨ and ¡§infiltrated into our language, body, desire and smell¡¨? After surveying the pictures and analyzing the irony of history or the malice of the homicide, what would again attract our gaze are the open wounds on the tortured bodies in ¡§Lingchi¡¨, the sliced open breasts, the cut knees, the castrated organs, the torn-out eyes, and the chopped-off heads. The gap on the body looks back at us and, like the ¡§punctum¡¨ described by Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida (1980), ¡§rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me¡¨ (26). But, the traumatic point presented by Chen Chieh-Jen is not the Barthesian ¡§punctum¡¨ either because, for Barthes, the punctum is what might escape people¡¦s gaze, what is already there but has to be added by the viewer, and this traumatic point is ¡§acute yet muffled, it cries out in silence¡¨ (Camera Lucida 53). Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s traumatic scene is acute and loud; it is the image of the castrated self, of the wound, and of the torturing gestures. Chen¡¦s gaze revolts against the ideologically dominating gaze, a mode of the gaze determined by the orthodox history. It is a gaze that questions and revolts against the surface of reality. Through looking into the mutilated and castrated, we see the absent, the excluded and the effaced, that is, we are faced with the un-sublimated performance of the obscene real, violence and destruction, undecorated and nude.

¡@

4. The State of Bardo: the lining of the visible reality

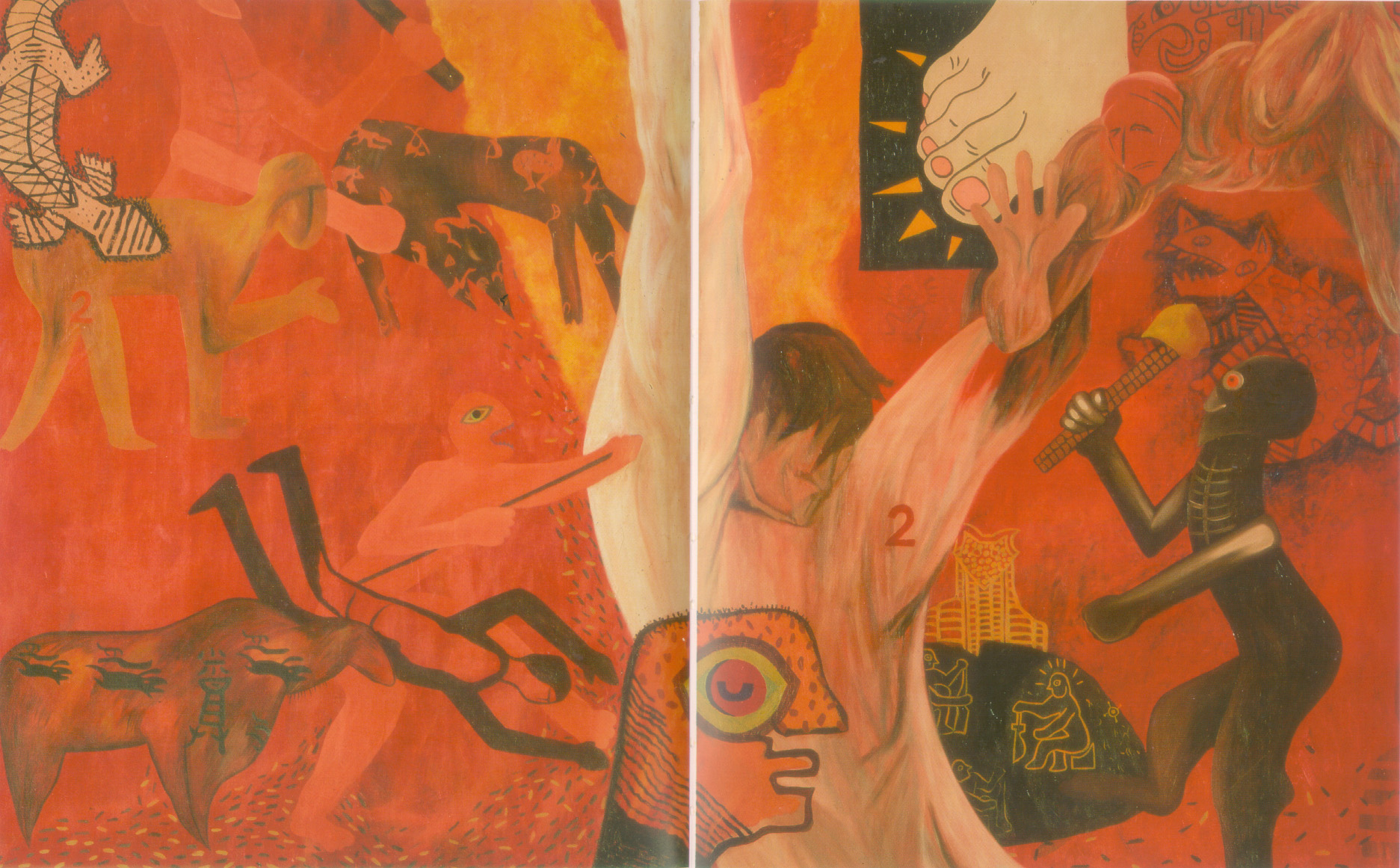

4.1 Violence of the Oedipal rebellion versus perversion and melancholy

When we browse through the works by Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s contemporaries, we¡¦ll notice that the surrealist or magical-realist presentation of the scene of violence could be found here and there, but in very different mode. In A Symptom of the World¡¦s End (1986) and Wounded Funeral (1993) by Wu Tian-Chang (1956-), or in The Scene of Killed Kun (1986) and Made in Taiwan (1991) by Yang Mao-Ling (1953-), or in Xingtian pieces (1991, 1993) by Hou Chun-Ming, we see certain pattern of violence, the violence in the act of fierce protest and accusation.

¡@

¡@

¡@

The violence in the act of protest exerts the Oedipal rebellious gesture attacking the paternal law while provoking punishment. This dynamics of violence could be found especially in the few years before and after the lifting of the Martial Law, from around mid-1980s toward the mid-1990s, an echo of the Kaohsiung Incident in 1979, but more in a rebellious gesture.

¡§The ¡¥Kaohsiung Incident¡¦ of 1979,¡¨ http://www.taiwandc.org/history.htm.

Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s mode of violence is different from this Oedipal rebellion because, instead of the juvenile revolt, his works expose rather the performance of an infantile perversion of the intermingled sadistic and masochistic subject positions in jouissance, followed by melancholy, a melancholy that is self-evacuating and non-objectal. Zheng Zai-Dong¡¦s severed head on canvas, for example, The Burning Memories (1994) and Drinking Alone Under the Moon III (1998), or his Cloth-Like Clear River (1998), represent the most typical example of such self-evacuating and non-objectal melancholy. [19] It is violence toward oneself.

¡@

The violence that is directed toward oneself cuts off the semiotic referential function in the representation. It is the violence that is aroused when the loved object which has been transplanted in myself is dead and when the cosmic system collapsed along with the death of the loved object. This melancholy happens when the god-like paternal figure is beheaded and the era of the firm faith is gone. [20] What the artists do, in the words by Hal Foster, is either to attack the image-screen, or to probe behind the image-screen ¡§for the obscene object-gaze of the real¡¨ (156): ¡§on the one hand an ecstasy in the imagined breakdown of the image-screen and/or the symbolic order; on the other hand a horror at this fantasmatic event followed by a despair about it¡¨ (Foster 165). Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s photographic images led us to experience these later stages of horror and of despair described by Hal Foster.

4.2 The lining of visible reality: the abjection and the abject

Regarding an exhibition Ritual in the Fin de Siecle: Contemporary Taiwanese Art held in 1999 in New York, [21] Huang Chinho, one contemporary Taiwanese artist, remarked that ¡§the current state of Taiwan is one of fearfulness, anxiousness, and uncertainty. This can be likened to the state of ¡¥bardo¡¦ (zhongyin) [22] described in Buddhism, a state that is also reflected in contemporary Taiwanese art¡¨ (qt. in Chang 9). The literal translation of ¡§Bardo¡¨ is ¡§between¡¨ (bar) ¡§two¡¨ (do). It is also translated as ¡§intermediate shadow,¡¨ a state between death and rebirth. Chang Fangwei, the curator of this exhibition, pointed out that this concept of ¡§bardo¡¨ suggests ¡§vitality¡¨ in the transitional stage of Taiwanese society, ¡§a leap from the state of death to that of rebirth¡¨ (9-11). To me, Chang¡¦s interpretation of the ¡§bardo¡¨ state, of the ¡§transition¡¨ and the ¡§leap,¡¨ appears too optimistic and automatic. What is significant in the state of the ¡§bardo¡¨ in Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s work, if we take it metaphorically, I think, is the in-between-ness of various states of consciousness. Looking at Chen¡¦s images of horror and fear, we are face to face with the lining of the human condition, separation, exclusion and violence, through which the past moments return, and the reality behind the moments of trauma and castration are also revealed.

Georges Bataille had discussed about the problem of our fear at the scene of violence and sacrifice. Automutilation or sacrifice in its essential phase, Georges Bataille explained, would only be ¡§the rejection of what had been appropriated by a person or by a group¡¨ (Bataille ¡§Sacrificial Mutilation,¡¨ 70). Similarly, the repugnance we experience in face of such images of the sacrifice, in Bataille¡¦s words, is ¡§only one of the forms of stupor caused by a horrifying eruption, by the disgorging of a force that threatens to consume¡¨ (¡§Sacrificial Mutilation,¡¨ 70). In a different writing, Bataille said, looking at the photographic images of a Chinese man having been tortured, fascinated and repulsed, ¡§as if I had wanted to stare at the sun, my eyes rebel.¡¨ Bataille said that he loved the young and seductive Chinese man, not with the love of sadistic instinct, but through the excessive nature of his pain, through his own seeking ¡§to ruin in me that which is opposed to ruin¡¨ (Inner Experience, 120, 123). The love-fear ambivalence in the feelings toward ruin and destruction, and toward self-abandonment in ecstasy, is central to Bataille¡¦s interpretation of the link between religious ecstasy and extreme horror.

Julia Kristeva clarified the mystical element in our ambivalence toward the fascinating and yet repulsive images of the violated and ugly bodies through her theories of the ¡§abjection.¡¨ Kristeva said, artist at boundary positions goes through abjection, ¡§whose intimate side is suffering and horror its public feature¡¨ (Powers of Horror, 140). The abject is the filthy and bad parts that the body/culture/history wants to cleanse away. It is not because of its lack of cleanliness that causes abjection, but ¡§what disturbs identity, system, order; what does not respect borders, positions, and rules; the in-between, the ambiguous, the composite¡¨ (4). We could not tolerate the ambiguous within us, the violence, the terror, the madness, in the same way that the culture executes its purgation. Sliced-open corpses, torn-out eyes, and severed limbs, are the extreme abject conditions that we fear to face. Through art, or through language, we see the artist¡¦s ¡§sublimation of abjection¡¨ in the scenes of violence, madness and jouissance, through the process of working-out and working-through¡¨ (Powers of Horror, 26). Going through or experiencing the process of the sublimation of abjection, we come to realize what had been suppressed or excluded within us.

Chen Chieh-Jen offered similar and yet very different explanations about penalty and the mutilation of the bodies. About penalty, Chen Chieh-jen said,

Penalty is a ritual of the embodiment of the structure of exclusion. In the entanglement of the torturer and the tortured, the spectator¡¦s gaze intervenes, and the penalty thereby infiltrates into the gaze. The gaze brings the ritual of penalty to a real climax that makes the subsequent extension of emotional effect possible.

During the ritual of penalty, what did the victims think at the agonizing moment of suffering and death? What kind of transmutations happened in the spectator¡¦s thinking while he gazes at the execution? How earnest was the executioner in his obsession with the techniques of execution? How did they develop this highly delicate techniques and manipulations of execution to extend the duration of the victim¡¦s agony, and the spectator¡¦s gaze? Why are the spectators, and we, bewitched by the techniques of this management? I wonder whether the victims painstakingly exposed their intention of committing the patricide by means of the transgression against the law, and I also wonder why the invisible but ubiquitous father can¡¦t escape his tragic destiny to kill his sons in fury, suspicion and phobia.Is it possible to find the map of their thinking and emotions from their faces or bodies? And, will this map be inscribed once again on the bodies of the spectators?

---From ¡§About the Forms of My Work¡¨

¡@

Chen said that his presentation of the images of penalty has nothing to do with ¡§redemption.¡¨ For him, the process of his works of art is ¡§a kind of voyage between turbidity and a sudden realization.¡¨ The extremity of torture and dismemberment, he added, serves as the bridge between the turbidity and the sudden realization, ¡§the rupture and rebirth by which we pass through the fear in the mind.¡¨ ¡§Cruelty always obstructs the spectators from looking into the photographic images.¡¨ Nevertheless, Chen asked, ¡§is the dark abyss of wounds not the very crack that we need to pass through so as to arrive at the self-abandonment?¡¨ This self-abandonment, the renunciation of the subjecthood, similar to the state in trance or in ecstasy, helps one to move in-between inter-subjective positions, with a-subjectivity and non-identity. Chen asked, are we not inscribed in our body the past histories, past experience, and past visions? To me, Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s magical-realist images fully expose the historical memories, both of the Chinese histories in the first half of the twentieth century, and of his own individual history and his childhood. These two dimensions , the collective and the individual, collide upon his photographic visions. What is more important, to me, is that his images hint at a special mode of the gaze: the gaze of Revolt, the gaze that leads us to question the flat explanation of our history, and to penetrate into the complex infrastructure of our past.

¡@

5. The Gaze of Revolt: Taiwanese conditions reinterpreted

Chen Chieh-Jen grew up in the neighborhood of the Martial Court and Martial Prison at Xindian, the location in which political prisoners are interrogated and put on trial, including the ones arrested in the Kaohsiung Incident of 1979. Chen said that what had been kept in prison pricked his curiosity ever since he was a child. His father is one of those veterans who came with Chiang Kai-shek¡¦s troops to Taiwan in 1949. His village was composed entirely by people like his father, who suffered through wars, came alone with the army to the island, leaving their families behind on the mainland, too poor to have a proper marriage in Taiwan and therefore married either poor orphans, or aboriginals, or handicapped persons. Chen said that the queer thing about his village was that many families had retarded children. He himself had one, who was not only retarded but also paralyzed, lying on bed naked throughout the years, till his death at the age around thirteen or fourteen. Chen shared the same room with this retarded younger brother, lived with him, and watched his death.

To Chen, he saw connectedness in all images and events: his being born in the veteran¡¦s village, growing up in the period of the Martial Law, in the neighborhood of the Martial Court, as a son of the veteran, with a quiet and hard-working mother, a moron as his brother, and so on. ¡§Through the process of modernization,¡¨ Chen said, ¡§history has been lingchi-ed, that is, chopped and severed as human bodies. We do not see where we are and what was before us. Violence is also gradually internalized, institutionalized and hidden. We do not see the violence of history or that of the State. We could only imagine it.¡¨ He further remarked that for those who grew up in the time of Martial Law, there¡¦s nothing to be seen or heard. ¡§The Martial Law period does not mean public persecution, but the condition that nothing real could be seen or heard.¡¨ (¡§Interview¡¨)

Indeed, Taiwanese people have not seen wars or public massacre ever after 1950. People under 50 grew up in a world of peace and stability. But behind the screen, there was the silenced fear. The bloody scenes of the massacre executed by the KMT troops in the February the Twenty-Eighth Incident had been hushed and suppressed right after the event and was banned from all forms of discussion or historical books. The sense of the unspoken and unspeakable fear and horror continued along with various transformations of intra-ethnic hostilities, secret types of political persecutions during the White Terror period, people disappeared and did not return. The forced transition, from naive faith in the Nation and the cheerful pictures of stability and democratic freedom, to slow and painful disillusionment, to the shocking knowledge of the traumatic history and the injustice, to the sense of conspiracy in the State cruelty, is the experience Taiwanese have gone through in recent decades.

What Chen has interpreted about the Martial Law period reveals a typical Taiwanese experience. Chen Chieh-Jen seems to suggest that the Taiwanese condition is the accumulation of layers and layers of histories before us. If we come back only to one historical point, the 2-28 Incident and its historical iconography, we then would be blinded by its fetishistic aspect and forget about the histories behind it. Unless we looked into the reality behind the history, we would not able to understand our own situation. When we really come back to the historical scenes, Chen also seems to suggest, we have to admit that the intra-ethnic malice does not only begin with the February 28th Incident and the White Terror. The malice is also related to the endless fights between the so-called Waishengren, and the Benshengren, the new comers after 1949 and the early immigrants, or the fights between Benshengren and Hakka, the forever alienated ¡§guest people,¡¨ the conflicts between the Han people and the aboriginals, and among the various tribes of the aboriginals. We should definitely also face the long wars between Kuomintang and the Communists on the mainland during the 1930s and 1940s, that is, Chiang Kai-shek¡¦s purging the communist party members starting from 1927 till the beginning of the Second World War, and the deadly Civil War between the Kuomintang armies and the Communist armies during 1946 to 1949, during which period of time millions of Chinese were killed by themselves. All these records of malicious battles are linked with the histories of violence and exclusion, the residues and vicissitudes of the supplices Chinois.

Chen described his method of synchronization of images, fusing his body image with the images in the past, as a state of trance, as if facing the mirror in hell, with the flashback of the imagery of the Karma. He said, ¡§for me, it is the re-emergence of the suppressed, repressed, and canceled memories.¡¨ We finally come to realize that Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s gaze of revolt is the gaze at the nude and obscene horror, through which the suppressed and repressed memories of our last generation return, painful and disgraceful memories that our parent generation would not like to and do not know how to talk about. Looking into the lining of the visible surface, the extreme state of horror, Chen Chieh-Jen has disrupted the objective gaze, the gaze from the State, and he has also eroded the subject-object binary relation through the objective gaze. He seduces us to look at the wounds with blood and the chopped-open corpses, the most repulsive and sickening images that we tend to avoid. In facing with such abject images, we also face the fragility and fluidity not only between life and death, but also between violence and joy, between sadistic and masochistic pleasures, and between the repetitions of historical violence. We learn to face the fact that what has been silenced are not only the 2-28 Incident and the persecutions under the White Terror, though it is indeed still a black hole in most Taiwanese people¡¦s consciousness. What had also been silenced are the crimes the Chinese had done to them during the first half of the twentieth century. The retarded and handicapped figures in Chen¡¦s later wasteland images, moreover, speak of the artist¡¦s repeated childhood perception of his village, and metaphorically also of the historically conditioned and trapped space and time he has been situated.

Chen calls his process of painting ¡§the process of writing the genealogy inside [his] body.¡¨ The process of working-through the fear, the repugnance and ecstasy in Chen¡¦s works, according to him, leads him from the state of turbidity to the state of full realization. The process of going through his photographic images, for us, has also led us to the answers to the questions we raised in the beginning of this paper: how do we face our history and where do we locate our subjectivity. In Chen Chieh-Jen¡¦s magical-realist scene of horror, we see a complex presentation of the sense of history and the sense of the local, through which our understanding of the history is pluralized, and our sense of the local is reinterpreted. Perhaps finally a little bit more tolerance for different positions could be allowed too.