|

Chen Chieh-jen��s Aesthetic of Horror and his Bodily Memories of History* Joyce

C. H. Liu ������������

There

looms, within abjection, one of those violent, dark revolts of being,

directed against a threat that seems to emanate from an exorbitant outside

or inside, ejected beyond the scope of the possible, the tolerable,

the thinkable. �XJulia

Kristeva, Powers of Horror [1]

�XChen Chieh-jen, ��About the Forms of My Works��[2]

����������

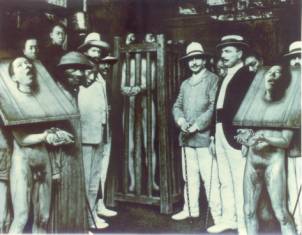

Chen Chieh-jen's photo-images of horror have had great impact not just on Taiwanese audiences but on Western viewers as well in recent years. Starting in 1996, Chen Chieh-jen embarked on a project, Revolt of Body and Soul. This series of works depicting cruel torture and violence, which has been exhibited internationally [3] , has attracted interest in the West in part because Chen in Genealogy of the Self (Ill . n�X 1) uses a photograph of lingchi (��death by slow slicing��) [4] that Georges Bataille reproduced in Tears of Eros. [5] My concern in this essay is not with the history of the aesthetic of horror in the West, which other scholars have already studied[6], and which can be illustrated with the hundreds of photos and postcards of ��primitive�� Chinese customs printed and circulated among Westerners[7](Ill. n�X 2). My concern, rather, is to consider what happens when a historic document of a lingchi execution�Xwhich in Bataille��s usage reveals an anthropological, even touristic Western curiosity about this primitive Chinese form of execution�Xcirculates back into the Chinese realm of representation. For the significance that Chen Chieh-jen��s images of horror have for Western viewers than is different from the impact they have on a Taiwanese audience. This essay is about Chen��s particular aesthetic of horror in relation to his project of reinterpreting Chinese modernity, first in response to the Western gaze, then as a commentary on Chinese forms of state modernity.

I�B Images of Horror Chen Chieh-jen was born in 1960 in Taiwan, the second generation

of those who moved with the Kuomintang (Guomindang, KMT) regime from

China to Taiwan in 1949. His father was forced to join Chiang Kai-shek��s

troops when he was in his teens, was moved from one battlefield to another,

and could never return home. The village to which he was transplanted

consisted entirely of low-ranking veterans like his father whose military

service deprived them of family, property, and whatever wealth they

had had. When they arrived in Taiwan and were allowed to form new families,

they could not afford the dowry required for a proper marriage, which

meant that most married poor orphans, aboriginals, and physically and

even mentally handicapped women. Most households in Chen��s village had

at least twelve children, some of whom were retarded. One of the boys

in his class at school was. Closer to home, one of own brothers was

not only retarded, but paralyzed. The boy lay naked on his bed until

his death at the age of thirteen or fourteen. Chen shared a bedroom

with this younger brother, lived with him, and watched his death. The

retarded figure that recurs in Chen��s photo-images reverberates with

his childhood visual experience in his own family.

�Ϥ@�G�P�s�w�m���ܡn�]���ϡ^ �ϤG�G���ɤ��m���ɹ�1947-1998�n���˸m���ҡ]�k�ϡ^

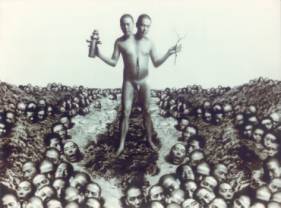

�ϤT�G���ɤ��m���ɹ�1947-1998�n The concept of ��lingchi-d history,�� of a troubled history bodily imagined, is the theme of Chen Chieh-jen��s artistic work. Our knowledge or ignorance of the past has eebn caused and constructed by the state during the process of modernization, he suggests; consequently there are gaps or ruptures in our knowledge of history. Recurring motifs of self-destructive Siamese twins and severed body parts reinforce this bodily imaginary of a lingchi-ed, or distorted and partially erased, history. The Communist/Nationalist rivalry during the liquidation period in the 1930s and the long civil war in the 1940s, the cold war of the 1950s on the two sides of the Taiwan Strait, and the cruel punishments the state executed upon its people during Martial Law: all constitute Chen's lingchi-ed history. The process of lingchi is simultaneously the process of modernization, through which the state institutionalizes social stigmatization and forgetfulness. Against this pressure to set aside or forget, Chen has connected images and events in the past and the present: the veterans' village, his Martial Law childhood, his Military Tribunal neighborhood, his own identity as the son of the veteran and a hard-working mother, the brother of an incapacitated boy. Chen's digital photo-texts interpret these historical conditions in which he was situated (Ill. n�X 3).[11] Chen has explained in an interview that the purposes of his project of Revolt of Body and Soul are twofold.[12] The first half of the series presents historical photographs taken between 1900 and 1950,[13] from the beginning of the modern era in China arbitrarily dated to the beginning of the century, to the year in which Martial Law was declared on Taiwan. The second half fictionalizes the state of affairs this internalized violence has produced.[14] Through these two sets of photographic images, Chen shows the cycling of violence and brutality, moving from external acts to internalized and institutionalized malice, from witnessed scenes of brutality to imagined sites of madness.

Furthermore, by placing his own image on the left side of the background as one of the onlookers, where he calmly observes the rest of the audience turning their attentive gaze to the executioner in order to participate in the moment of thrill, Chen creates a third dimension of gaze. This play of the gaze imparts irony to the picture: the gaze of the people within the frame absorbed by the execution, the gaze of the camera/the West and the apparatus of the power system involved, and the contrasting gaze of the modern onlooker which highlights the temporal uniqueness of the execution, the moment in which Chinese modernity is about to begin.

II�B Abjection and the Abject:

A Process of Working-through Even with

the Foucauldian questions that Chen Chieh-jen��s photo-images raise,

we are still faced with the images themselves of horror and fear. Georges

Bataille��s understanding of the fear we experience in the presence of

auto-mutilation or sacrifice is that this type of act is a ��rejection

of what had been appropriated by a person or by a group.�� The repugnance

we experience before such images, in Bataille��s words, is ��only one

of the forms of stupor caused by a horrifying eruption, by the disgorging

of a force that threatens to consume.��[21] Bataille

has described his own fascination and repulsion when looking at photographic

images of a Chinese man being tortured in these terms: ��as if I had

wanted to stare at the sun, my eyes rebel.��[22] He

loved the young and seductive Chinese man, he wrote, not because of

a love of sadistic instinct, but because the excess of the victim��s

pain compelled him to seek ��to ruin in me that which is opposed to ruin.��[23]

This love-fear ambivalence in his feelings toward ruin and destruction,

and toward self-abandonment in ecstasy, is central to Bataille��s interpretation

of the link between religious ecstasy and extreme horror. �ϥ|�G���ϬO�m���ϡn�Ҩ̾ڪ��Ӥ��M���ۤڥN�C (Georges Bataille)�m�������\���n(Tears

of Eros) �Ϥ��G�k�ϬO��Ѭz�L�檺�u����ŦD�t�C�v�ĤT�����H���M�\���@�E�@�G�~���뢸��Ѭz�l�W�M���ۡm�¹ڭ���G�M�N���H���ﶰ�n�C

�Ϥ��G���ɤ��m���ϡn

�ϤC�G���ϡM���ɤ��m�h�չϡn�Ҩ̾ڷӤ��M��v�̤��ԡM��Z��m������v�v�n�M56���C���ɤ����ѡC �ϤK�G�k�ϡM���ɤ��m�h�չϡn

Still,

what is most significant about these past lives to Chen is the sense

of history they embody. ��The histories I am much concerned about are

the histories excluded by the orthodox power, that is, the histories

outside the history. Moreover, I��m even more concerned about the histories

that survive in the realm of ecstasy, like lacunae among words, concealed

in the midst of aphasia, infiltrated into our language, body, desire

and smell.��[27] As we look into Chen��s photographic

images, we see not only the past memories and past lives of Chinese-Taiwanese

flashing back, but also something behind the scene of history, something

related to the bodily memories. Chen has declared that he wants to ��gaze��

(ningshi) into the images of historical horror, as the dead

gaze into the Mirror of Sin, so that he can ��penetrate�� them:

�ϤE�G���ϡM���ɤ��m�۴ݹϡn���b��Ҩ̾ڤ��Ӥ��C��v�̤����M�F�_�M�ҷӤ��M���ɤ����ѡC �ϤQ�G�k�ϡM���ɤ��m�۴ݹϡn�k�b��Ҩ̾ڤ��Ӥ��CJay Calvin Huston�@�E�G�C�~����ҲM�Үɴ��b�s�F�ҩ��᪺�Ӥ��M���ɤ����ѡC

�ϤQ�@�G���ɤ��m�۴ݹϡn

Why images of

horror? ��Cruelty always obstructs spectators from looking at the photographic

images,�� Chen once observed; nevertheless, he asks, ��is the dark abyss

of wounds not the very crack that we need to pass through so as to arrive

at self-abandonment?�� What is this self-abandonment? It is the renunciation

of subjecthood, the capacity to move inbetween intersubjective positions,

to assume asubjectivity and nonidentity. The extremity of torture and

dismemberment serves as the bridge between blindness and sudden realization,

��the rupture and rebirth by which we pass through the fear in the mind.��

To Chen, the art process is ��a kind of voyage between blindness and

sudden realization,�� similar to Kristeva��s notion of ��working-through.��

�ϤQ�G�G���ϡM���ɤ��m���n�ϡn�Ҩ̾ڷӤ��M�@�E�|���~���Դ����R§�ƥ�M�����q�T�����������~������Ӥ�(#2100)�M���ɤ����ѡC �ϤQ�T�G�k�ϡM���ɤ��m���n�ϡn

What

then is this blindness? What realization can be obtained? By working

through the historical images of horror, Chen has said, he enters into

the layers of history he sees inscribed on his own body. These inscriptions

are the past histories, past experiences, and past visions to which

the state��s education makes us blind. This realization Chen acts on

through his method of art production: �ϤQ�|�G���ɤ��m�k�v�ϡn

His artistic work thus brings Chen into an encounter with the pastness, the Other, the history that he has experienced in his own body.

�ϤQ���G���ϡM���ɤ��m�鱫�ۡn�F�ϤQ���G�k�ϡM���ɤ��m�s���n

�ϤQ�C�G���ϡM���ɤ��m���\�ۡn�F�ϤQ�K�G�k�ϡM���ɤ��m�������n

III�BBodily Memories of History

For

these reasons, Chen��s notion of ��lingchi�Ved history�� speaks

to a Chinese audience. People on the mainland and on Taiwan share different

understandings of history and different emotional memories of it. Their

bifurcated histories have been constructed by their political regimes

through different systems of imprisonment that work culturally at the

same level of technological sophistication that lingchi can be said

to represent. This perspecitve on the ways in which the artist imagines

and interprets his world declines to distinguish art from history and

politics. Through his visual work, Chen makes the cuts and wounds on

the bodies of the tortured signify not bodily cruelty, but his subjective

emotion, certainly violent, also sado-masochistic, toward the object

of his contemplation. He calls this artistic work ��the process of writing

the genealogy inside the body.�� Working through the fear, the repugnance,

and the ecstasy, according to Chen, leads him from blindness to a state

of full realization.

Chen

has also described his method of synchronizing images, of fusing his

own body image with images from the past, as a state of trance. It is

as though he were facing the mirror in hell and seeing this historical

imagery as karmic flashback. ��To me,�� he says, ��it is the re-emergence

of the suppressed, repressed, and canceled memories.�� The retarded and

handicapped figures in Chen��s later wasteland images thus speak of the

artist��s repeated childhood perception of his village, the Military

Tribunal, and metaphorically also the historically conditioned and trapped

space and time in which history has situated him. We come to realize

also that Chen Chieh-jen��s photographic gaze�Xthe gaze at the naked and

obscene horror�Xallows the suppressed and repressed memories of the previous

generations to return, painful and disgraceful memories that his parents��

generation would not like to and do not know how to talk about. Starting

from his dismembered memories and truncated understanding of history,

he takes us back through this ��lingchi-ed�� history to the moments

and sites of the variations of the lingchi. He leads us to look at the

bodily wounds, the most repulsive and sickening images which we tend

to avoid, so that we too face the fragility and fluidity not only of

the boundary between life and death, but also the point of difference

between violence and joy, between institutional sadism and masochistic

pleasure, between historical violence and its repetition.

Note: [1]Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, p. 1. [2] Chen Chieh-jen��s statement, ��About the Forms of My Works,�� appears on the website: www.asa.de/Perf konf/Reader2/Reader2-1.htm#ChenAbout. [3] For example, the 48th Biennale di Venezia (Taiwan Pavalion) in 1999 in Venice; the International Photography Biennale, Centro de la Imagen, in Mexico in 1999; the 5th Biennale de Lyon Contemporary Art, Sharing Exoticisms, in Lyon in 2000; The Mind of the Edge, Photo Espana, Circulo de Bellas Artes, Madrid, in 2000; the 31st Rencontres Internationales de la Potographie, Abbaye de Montmajour, Arles, 2000. His works have been published in Warsaw in the magazine Max,1999, no. 6. [4]Lingchi, torture by slicing, was supposed to inflict a thousand cuts on the body of the executed before he died. People gathered at the site of execution to obtain the victim��s blood and flesh for medicinal uses. See Wang Yongkuan, Zhongguo gudai kuxing. [5]This picture and Bataille��s commentary appear in Bataille, The Tears of Eros, p. 204-207. Bataille notes that this picture was previously published by Dumas in Traite de psychologie (Paris, 1923) and by Carpeaux in Pekin qui s��en va (Paris, 1913). He follows Dumas in identifying the tormented figure as Fou-Tchou-Li, who is the figure in Carpeaux��s picture, but this is not correct (see Jerome Bourgon, ��Bataille et le supplicie chinois: erreurs sur la personne��). Bataille recorded that he was given this picture in 1925 by the psychoanalyst Dr. Borel. ��This photograph had a decisive role in my life,�� he confessed. ��I have never stopped being obsessed by this image of pain, at once ecstatic (?) and intolerable.�� It led him to conclude his study of eroticism with the discovery that there existed an ��identity of these perfect contraries, divine ecstasy and its opposite, extreme horror.�� [6]Claire Margat's ��Esthetique de l��horreur�� presents a comprehensive account of this issue. [7]The series of postcard was entitled as ��Les Supplices Chinois.�� This one was mailed in July the 9th of 1912, from Tien-tsin, to France. This postcard is taken from Jiumeng Chongjing, a collection of old postcards edited by Fang Ling, Chen Shouxiang, and Bei Ning. [8] In the Gaoxiong Incident of 1979, the Nationalist military and police broke up the island's first major Human Rights Day celebration (10 December 1979), and subsequently arrested and imprisoned virtually all leading members of Taiwan's budding democratic movement, including current president Chen Shuibian and vice-president Liu Xiulian. The incident galvanized people��s political conscience both then and over the following years. An outcome in September 1986 was the formation of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) as a full-fledged opposition party. [9]All references to interview material are to the author��s unpublished interview with Chen Chieh-jen, 28 July 2000. [11]See for instance The Image of Identical Twins (1998). [12]Ibid. [14] Image of An Absent Mind (1998), The Image of Identical Twins (1998), Na-Cha��s Body (1998), and A Way Going to An Insane City (1999). [15]According to the Central News Agency, the photograph

(#2100) was taken around the December of 1946, in the battle at Chongli.

In fact, the battle took place on 9 November 1946, when the Communist

army occupied Chongli, north of Zhangjiakou, killing several thousand

civilians. Chen Chieh-jen says that the Central News Agency��s filing

system might be wrong, because when he first looked at this picture,

before they started their filing program, it was located among a group

of pictures taken after Chiang Kai-shek��s armies took Yan��an. [17] Elkins, The Object Stares Back, p. 115. [18]The number of military deaths in one battle could reach up to 100,000, as it for example in the battles at Jinzhong and Jinan, 1948. [19]Chen Chieh-jen deals with this theme in his Rules of Law. [20]Chen Chieh-jen, ��About the Forms of My Works.�� [21] Bataille, ��Sacrificial Mutilation and the Severed Ear of Vincent Van Gogh,��in his Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927-1939, p. 70. [22]Bataille, Inner Experience. p. 120. [24]Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror, p. 140. [27]This and the following quotations are all taken

from Chen Chieh-jen, ��About the Form of My Works��; see note 2 |