Activity Report: Hidden Hostiries and Radical Care

2022-06-29

Transit Asia Media Lab Lectures Series

Hidden Hostiries and Radical Care

lecturer: Valerie Soe, Professor, San Francisco State University, ICCS Visiting Scholar

Sidelight:IACS-UST Ronald Shum

Photo credit:SRCS Yuling LI

TIme:2022 / 04 / 25

Location:HC Building II Room106A, NYCU GuangFu Campus

Professor Valerie Soe from San Francisco State University shared with us her experiences and thoughts on the topic “Hidden Histories and Radical Care” this day. Taking the lively experience of Asian Americans as the locus, She concern in what way were non-white immigrants in America being treated unequally, unfairly and violently.

1990 was a turning point where immigration of Asian into America has rise drastically. Long before that, numerous number of Chinese Coolies(苦力)have already been imported into the United States since the former century to provide cheap labour. They contributed into important infrastructures such as the First transcontinental Railroad. However, sinophobia has not ceased in the American history, Chinese immigrants and laborers suffered from racial discriminatory representation as well as violence. People were harassed, attacked and expelled from their settling town or even from the country.

These historical roots led to its interlocking relation with present sinophobic violence and discrimination to ethic Chinese American since the outbreak of COVID-19 in the US. Though some people from Hong Kong and Taiwan may have an impression that the world’s growing hostility to China would be useful in drawing more attention CCP’s oppressive state violence; in its effect, sinophobia is far more than mere hostile against an authoritarian state. sinophobia linked intimately to racial discrimination and exclusion to all ethnic Chinese, and even to all asians, whom were apparently not differentiable to most white Americans. They could not tell the difference between Chinese, Japanese and Korean, not to mention inner diverse groups among ethnic Chinese.

Under her observations and reflections, professor Soe shot her first experimental short video work “All Orientals Look the Same”. It was just a one-minute-and-a-half short clip in black-and-white. The faces of asians from different nationalities emerged and faded one by one. A voice-over from a white person kept saying: “all orientals look the same”, while another voice-over added the place of origin after each face was shown (which was in fact not the precise origin of that face). The identifiability between a face and its nationality were displaced and dislocated. Can we really tell where did one come from, just by looking at their place? The diversity of Asian American was always unseen before the eyes of American Whites. More than that, in creating short clips, Soe also intended to shake up the domination of “longer” duration filming deployed in the television. To film shortly seems to be itself a gesture to align with contemporary audience who were more used to short clips.

The Second work shared by Soe was “The Chinese Garden” in 2012. There was a Chinese settlement in Port Townsend called Chinese Garden. As mentioned above, imported Chinese laborers formed early Chinese settling sites in the 19th Century. As Laws of Chinese exclusion were introduced, including the Page Law (1875) and the Angell Treaty (1880) , Chinese immigration were discriminated and further banned. The 1880s was marked by bloodsheds against Chinese, whom were either killed or forced to be expelled. Chinese immigrants who settled in Port Townsend were among the victims of these waves of discriminatory violence. In the present-day Port Townsend, the once-existing Chinatown has left all but its silhouette. The original site have been burnt down (while the white living neighbor was saved from the fire). Narrating these hidden histories in her own poetics of images, Soe attempted to reclaim the lost historical meanings from the fumes.

As Covid-19 broke out around the globe, health crisis became a new threat to the racially and ethnically marginalized. As the U.S. federal government was inactive at the beginning in handling the crisis, there was a general scarcity in health-care goods such as face mask and PPE. In view of this, a number of volunteers, mostly female and come from non-white origin, grouped together via Facebook. They worked collectively to sew face masks for health-care workers, immigrants and the economic fragile. At its peak, there were about 800 members among the group.

Soe both participated in the campaign and collected the documentation of individual process of sewing. At the times of the pandemic, especially during lockdown, individual volunteers were also living in isolation mostly locked up in their four walls. Yet they can film their own sewing process and show one another that they were actually working together. As the different groups and ethnicities especially the marginalized allied one another at the times of crisis, a new social network in a form of “radical care” was formed. In view of this, I couldn’t help but think of Judith Butler’s political idea, where the people of precariousness and dispossession formed an alliance without the need to claim essantialities, and to fight for social support and care precisely at the age of neoliberalism.

近期新聞 Recent News

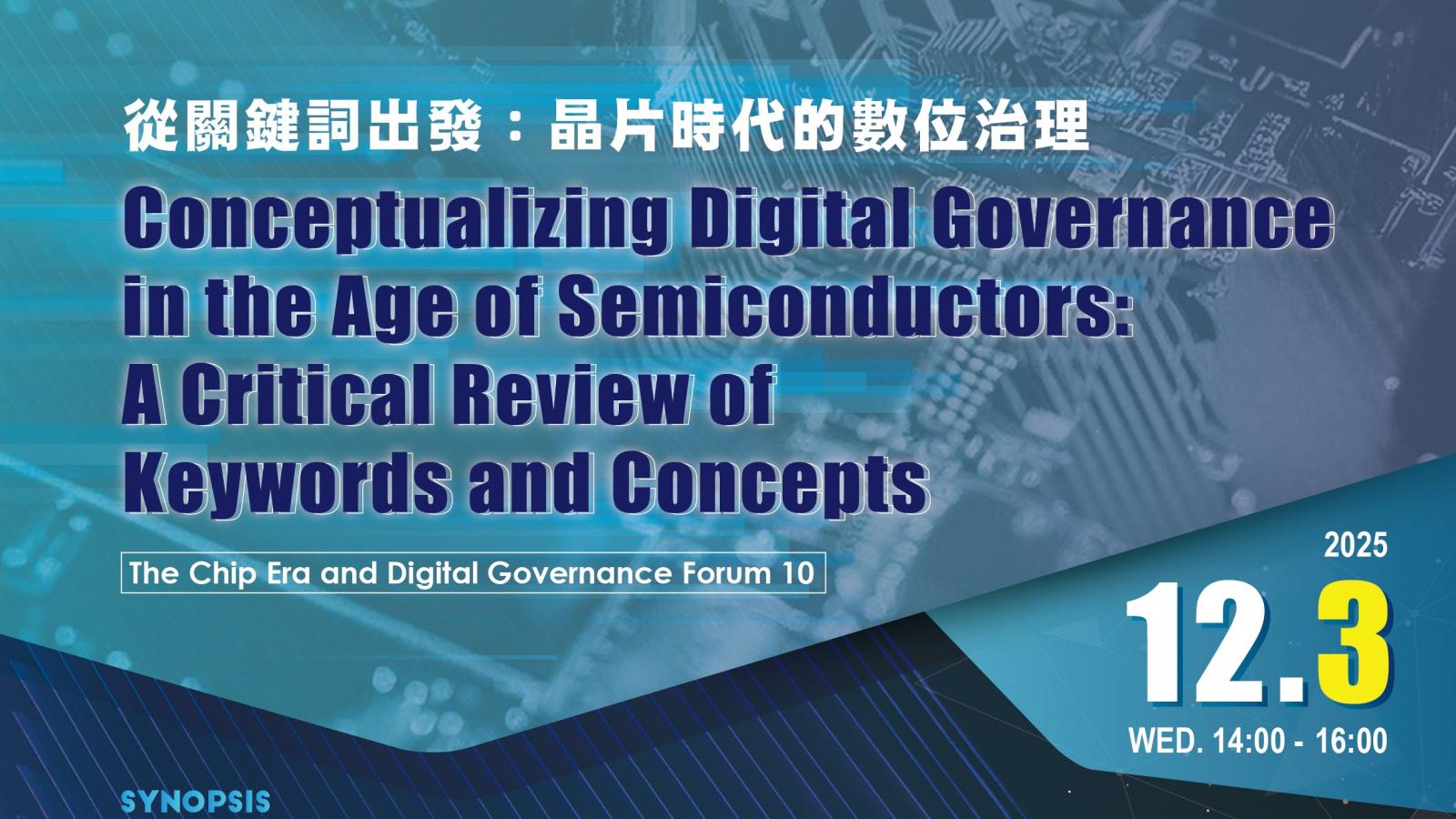

Report|Conceptualizing Digital Governance in the Age of Semiconductors: A Critical Review of Keywords and Concepts

2025-12-03

more

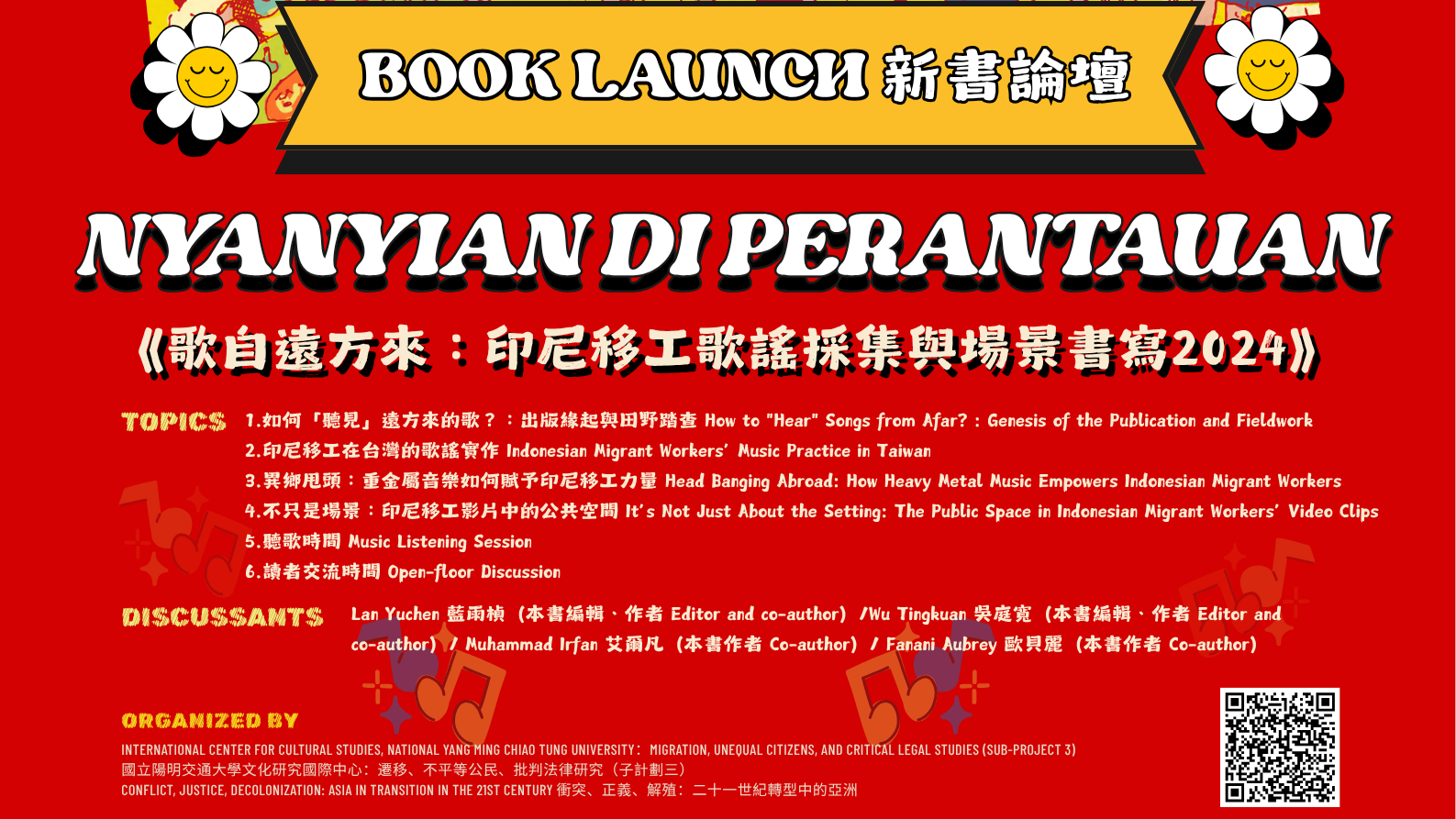

Report| Book Launch: Nyanyian di Perantauan: Kumpulan Lirik Lagu Pekerja MigranIndonesia & Laporan Skena Musik di Taiwan 2024

2025-11-22

more