Palace Museum vs. the Surrealist Collage:

Two Modes of Identity Construction in

Modern Taiwanese Ekphrastic Poetry[1]

ˇ@

Copy Right.

Joyce C. H. Liu

Graduate Institute for Social Research and Cultural Studies National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan

Published in Canadian Review of Comparative Literature. 24.4(December 1997): 933-946.

IˇBTwo Modes of Taiwanese Ekphrasis Poetry

IIˇBThe Diaspora Poets of the 1949 Generation: Yu Guangzhong & Ya Xian

IIIˇBThe Ekphrastic Poets of the New-born Generation: Su Shaolian & Chen Li

IVˇBConclusion

VˇBWorks Cited

VIˇBFOOTNOTES

In recent years I've been working on interart projects and re-examine the intertextuality between modern Taiwanese literature and the other arts. To be more specific, in order to discuss in a wider scope the formation of Taiwanese cultural imaginary, I tried to relate literature and the other arts, and see, for example, how the visual culture and visual imagination have shaped the perspectives and modes of representation in verbal texts, or how visual icons have been quoted and remolded in the verbal text as a strategic disguise for other political purposes. To me, the intertextuality between different art forms inevitably involves ideological agenda, such as gender, race and identity construction. In a previous project, I discussed the influence of the visual arts and the political motivation behind the transplantation of Surrealism by Taiwanese poets in the 1950s which triggered the modernization of Taiwanese poetry.[2] The aim of this paper is to discuss the two modes of identity construction, the Mode of the Gaze and the Mode of the Glance, or to put it in a more figurative and culturally coded terms, the Palace Museum Mode and the Surrealist Collage Mode, in modern Taiwanese ekphrasis poetry, poems speaking about visual arts, and show how the two generations of poets strategically and rhetorically address to the silent plastic objects for different contextual purposes. In my discussion, as the reader will soon find out, ancient China frequently appears as an absent Other, a cultural Other in the process of identity construction for Taiwanese poets. Either the diaspora of the 1949 generation or the new-born younger generation who write in the 1980s and 1990s, this sign of the cultural Other serves as a target for dialogue. In this paper, I take Yu Guangzhong and Ya Xian as a pair of contrast among the poets of the first generation, Su Shaolian and Chen Li for the second generation.

ˇ@

I Two Modes of Taiwanese Ekphrasis Poetry

IIThe Diaspora Poets of the 1949 Generation: Yu Guangzhong & Ya Xian

In his study of intertextuality, Riffaterre points out that the "absent intertext," or the semiotic gap, disturbs the structure of the current text, and results in the "ungrammaticality" in the textuality. This ungrammaticality points to a "syntagm situated elsewhere": "the text's ungrammaticality is but a sign of a grammaticality elsewhere, its significance a reference to meaning elsewhere" (Riffaterre 627). This ungrammaticality, moreover, opens up the ambiguity of the text and its signification process. To perceive the relations of text to its quotations or presuppositions, according to Riffaterre, we need not only linguistic competence, but also cultural competence (628). But the "syntagm situated elsewhere" suggests to us not only of the cultural and linguistic syntagms; it also suggests a space relaying the poet's unconscious and his idiosyncratic personal history, filled with linguistic, cultural, political, and erotic desires. The ekphrastic object, furthermore, is presented as the presence of an absence, and hence the target of desire becomes opaque. The absent Other, whether it is the "mother" which nourishes the bitter gourd, the sound of the wind and the legends behind the Tang horse, or the empire the Chin Clay Warriors guarded, is the negative of the plastic object, the invisible, the ungraspable, alluring and elusive. The feminine quality W. J. T. Mitchell as well as Francois Meltzer rhetorically attribute to the ekphrastic image in their theorization of the ekphrastic text then becomes significant, because the "unapproachable and unpresentable black hole" (Mitchell 700) and the "seductress as an icon" (Meltzer 26) draw the complex attraction/resistance dialectics between the poet and the graphic object to the foreground, as well as the poet's anxiety for merging with the Other. Through the semiotic gap occurred in the interart intertextuality, and the gendered relation between the verbal text and the graphic object, I think, we can obtain a better glimpse into the poet's strategies of the representation; for the present project, the issue concerns the construction of the national/cultural identities in modern Taiwanese ekphrasis poetry.

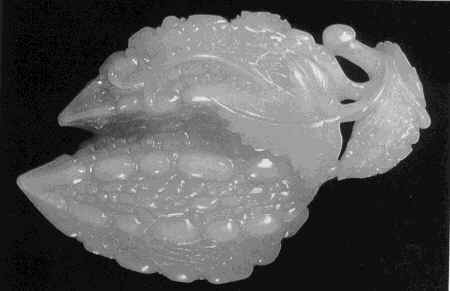

Among modern Taiwanese ekphrasis poetry, I find two opposite modes: one speaking about classical Chinese visual art, the other addressing to western modern paintings, especially of the surrealist style. The verbalization of classical Chinese art work, a sculpture, a vase, a jade object or a painting, frequently betrays a spatialized representation and relocation of the poets' temporal memories of the historical China. I would like to call this ekphrastic rhetoric the Palace Museum Mode, or the Mode of the Gaze. [4] In the opposite group, poets invoke western avant-garde artists, such as Matisse, Dali, Miro, Chagall, Delvaux, and re-organize their interpretation of the western paintings through a collage of disassociated images.[5] Through their interpretation, the West has become a collage of Taiwanese experience. I would like to call this second ekphrastic rhetoric the Surrealist Collage Mode, or the Mode of the Glance.[6] In the Mode of the Gaze, the poet stands still in front of one plastic object, gazes at the object, worships it, and his envoicement follows a centripetal movement. It is as if he wants to enter the object through his reading and become one. But, the masculine gesture in it and this attachment seems to reveal a hidden separation and disengagement. In the Mode of the Glance, however, the poet glances at one art work after the other, as if passing through the gallery, selecting random details, piling them up in an irrational and illogical manner. The poet seems to avoid being tied up by one object, but, through his feminine sideway glance, there is an even stronger lust and hostility for the absent. Either the pieces of treasures housed and stored up in the Palace Museum, or the distorted and unrelated images lumped together through the surrealist collage, the verbal canvas frames up a local/Taiwanese experience in confrontation with the cultural Other.

In talking about "cultural identity," Stuart Hall suggested that there are at least two different positions: the first defines cultural identity "in terms of one, shared culture, a sort of collective one true self', . . . which people with a shared history and ancestry hold in common" (393); the second recognizes that "there are also critical points of deep and significant difference with constitute what we really are'; or rather -- since history has intervened -- what we have become'" (394). The choice of positions reflects political considerations. In reading modern Taiwanese ekphrastic poetry, we'll find that these two different positions cannot be a clear-cut distinction. Poets shift from one pole to the other, searching for origins either in ancient Chinese culture or in ancient Taiwanese culture, but occasionally, they linger in the limbo space of uncertainty, facing the multivalent changes of current society and culture, with no fixed point of settlement.

A Yu Guangzhong and the Mode of Palace Museum

The ekphrasis genre concretizes Yu Guangzhong's nostalgia for China, his homeland and his spiritual origin. Nostalgia is a recurring motif in Yu Guangzhong's poetry. [7] Early in 1960s, the Beat Generation, after his exile from China, Yu travels in US. His nostalgia for the home country is combined with his memories for his deceased mother and his troubled identity as a Chinese, China is represented in his poetry not only as the poet's mother, as his own body, but also as a trade mark of shame.[8] But, as Jian Zhengzhen points out, in Yu's nostalgia poetry, even early in the 1960s and 1970s, there's an obvious dialectic tension in the conflict between the longing for return and the awareness of the impossibility of this return (Jian 103, 120). I would suggest that, besides the awareness of the impossibility of the return, there's even a hidden effort of disengagement in the poet's poems to remove the influence of China from his world. We can see this effort clearly even in the poems of ekphrastic mode during 1970s, not to mention the ones in 1980s.

Looking at the art object, either it is the "Jade Bitter Gourd" ("Baiyu Kugua" 1974), the "Tang Horse" ("Tang Ma" 1977), the photos of the "Yellow River" ("Huanghe" 1983), the "Chin Clay Warriors" ("Chin Yong" 1988), or the "Chinese Knot" ("Zhongguo Jie" 1988), the poet summons up the past history of these objects, verbalizes the unspoken desires and inactivates hte lives within these objects. These still and silent images become the history of ancient China, or the mother image, the mother which has nursed him, nourished him, but now is severed by force after his exile from China. The Jade Bitter Gourd at the Palace Museum in Taipei which the poet speaks to invokes such mother-child relations:Look at your winding and intertwining vines, your embracing leaves,

As if you want to suck to the last drop, in the year of the abundant harvest,

The milk endlessly fed by the ancient China.

The perfect roundness, happy and content. (6-9)The vast nine states have condensed into one map;

You did not know to fold it when you were a child:

Spreading it out, the boundless,

Immense as the memory, of the Mother, of her breast.

Crawling to the land of fertility,

You seek for her merciful juice with your roots and your stems. (13-18)The image of the mother earth is the invisible world, the absent Other, envisioned by the poet behind the Jade Bitter Gourd. From these lines we see a clear Mother Earth imagery, abundant harvest, endless milk, perfect roundness, boundless, immense, fertility, and rhetoric of closeness and of touch, such as the winding and intertwining vines, embracing leaves, sucking, and so on.[9] Similar construction of the imagery can be found in the "Tang Horse", the photos of the "Yellow River", or the "Chin Clay Warriors". The poet sees the wind and the sand of the frontier land, hears the neighing and the hoofs of the horses, and the legends of battles and of heroes through the Tang Horse; the poet also pictures the bare breast of the northern plain and the milk-like Yellow River on the photo, or visualizes the ancient empire reflected in the Chin Clay Warriors. We see that the poet has attributed "Chineseness" into these plastic objects.

ˇ@

The crystallization of the cultural memories into the ancient Chinese art objects, however, reveals clear strategies of disengagement. The gendered position the poet takes in treating the ekphrastic object, for example, implies a tone of separation. The poet in "Jade Bitter Gourd" searches with his pen for the memories of the past, as the Bitter Gourd's vineˇ¦s entering the breast of the Mother, entering and penetrating. The phallic impulse of the pen to suck, to search, to penetrate, and to speak for the silent image assumes a masculine gesture. The act of envoicement paradoxically is to silence, to feminize and to freeze the memory into a graphic image.

The attraction/resistance dialectics and the anxiety for merging with the cultural Other, as we see in Yu Guangzhong's ekphrastic poetry, are best reflected in the process of the building up and cementing of the "wall" of the Palace Museum, or the "glass wall" we see in the Jade Bitter Gourd. The miraculous existence of the Jade Bitter Gourd, of the crystallized memory of the past, is preserved as intact and severed from the gazers by the "glass wall".The entire mainland loves solely this Bitter Gourd,

Trampled over by the boots and hooves,

And the belts of the weighty tanks;

No trace of wound has been kept.Only the incredible miracle separated by this glass remains. (21-25)

The sense of separation maintained by the glass wall also appears in other ekphrastic poems by Yu. In "Tang Horse," it is the "glass closet" (15) which separate the horse from reality. The "glass closet" frames a "transparent dream" (21) and executes the "open imprisonment" (32), in which a lonely horse stands on the "soft green velvet pad, a tiny meadow, stirring no warring dust" (16-17).

You lonely horse, lost in this glass closet;

The soft green pad underneath your hooves,

Is like a tiny meadow which stirs no warring dust.

. . . .

Can you kick through this transparent dream?

Break the glass into pieces, and run away? (Ll. 15-22)

The Tang horse, which used to fight numerous battles, galloping on the open field, is an embodiment of the past glory of the Tang Dynasty. The entire Chinese history of the battles is invoked and also condensed through the horse figure. But now the horse is locked up in the sound-proof museum; the sounds associated with the warring horse, the wind, the galloping, the battle drums, the horse neighing, and the legends of the heroes, are all locked up as well. The imprisoned, feminized and silenced plastic figure conveys the impotent and castrated cultural experience.

The semiotic marker of the "glass wall" and the "glass closet" separates the present from the past, and separates the poet from the Mother, so that the speaking subject can begin to view the past as an objectified difference, and then to construct his own individual identity. The ancient China in the poet's memory is like a "disappearing empire" (42) or an irrevocable Peach Blossom Spring (20) in "Chin Clay Warriors". The poet asks the clay warriors:

Your armors are still on, and your hands holding tightly

The arrows or spears which I do not see.

If the warring drums suddenly rise up,

Would you turn right away, and run to the battlefield of two thousand years ago,

And join the rows of warriors? (1-6)No! "The history has been written, the land is lost, and the palace is burnt. You cannot return any more. You are forever the prisoners." Answers the poet to his own questions.

Tongguan is besieged, Ah, Xianyang lost.

Who comes to rescue the fires of the Ahfang Palace? Only you, who stay,

You who can never return, who have become

The hostages of the next generation, the eternal prisoners. (49-52)But the past is darkness and a dead-end. Thus, he continues: "You are the honorable descendants who didn't follow Qin Shihuang into the past, but came with Xu Fu to seek eternal life." The eternal life is possible only at a land for the future, at the legendary island Penglai. They become the diaspora in Taiwan, like the poet himself. The diaspora in Taiwan cannot return "home," and they also refuse to return. The umbilical cord which extends in the poet's imaginary through the Jiuguang railway to the "vast, benign but estranged body of the Mother" in "Jiuguang Railway," but in "the Chinese Knot" the poet has cut up the umbilical cord and sent it back by to the remote mountains of the mainland, while the sea coast of the island, according to the poet, is closer to the poet's heart.

The act of staging the plastic object as ancient cultural memories is like visualizing and concretizing the past into a map. The poet in "Jade Bitter Gourd" says, "The vast nine states have condensed into one map which you did not know to fold when you were a child" (13-14). Listing the names of the places and the spots of time as if through map-reading and history-enchanting thus becomes a compulsive act. Map then appears in Yu's poems and prose essays as a recurring motif, as in many other poets' works.[10] But, to traverse, to read, to visualize and to enchant the past is in fact to flatten and to control the past so that it does not exist as a chaotic mass or overflow. The past which is retrieved rhetorically through naming is metaphorically flattened into a map which the poet can fold and put it aside.

The museum collection of the still moments of perfection in Chinese cultural history manifests one mode of representation of China as the cultural Other; for the diaspora in Taiwan, the memories of the cultural past are like the pieces of treasures safely housed and stored up in the Palace Museum, blocked with glass closets.[11] They can visit the museum, pay the tickets, contemplate over the still art objects, as if they are the effigies at the sanctuary, retrieving bits of memories, and then return to reality. The centripetal movement of envoicement works like the gaze which objectifies the visual focus as if building up a citadel; when the narrative is finished, the gazed object is blocked inside the citadel and is forever separated from its gazers.

˘Đ Ya Xian and the Surrealist Collage

The examples of Yu's ekphrasis discussed above were written during the 1970s and 1980s when the root-seeking movement and the cry for autonomy in Taiwan were on the start. Such sentiment was not allowed in the 1950s, when the Cold War was still on. Yu's nostalgia was expressed in "Variations of Tianlangxin" (1961) under disguise.

Noah, Dayu, the people who are still unaccustomed to the earth over these thousand years,

Like the extinguished phoenixes,

The destroyed dragons;

The foot prints, the star light. There is no exit for mankind.Such distorted and suppressed voice is more clearly seen in Ya Xian's "To Matisse" ("Xiangei Matisi"), a surrealist ekphrastic poem.

The surrealist's stress on automatic writing, free associations, irrational collage of images taken from different planes of reality, and nightmarish atmosphere, help liberate the unutterable and the suppressed to be transformed and replanted on a crowded plane.[12] In "To Matisse" (1961), the reader sees a collage of disassociated images taken from several paintings by Matisse,[13]In your eyes burns the Notre Dame. In the playroom

The naked bodies slowly rise up and tease those angels.

No echoes. The speckled leopard squatted in the dark corner.

Your hands which weave all coincident disentangle the hair coil.

Under the heavy stroke of the electric guitar,

In the dangerous frontier of some unknown dreams,

These golden women lie

On the blanket knitted with roses. (2-9)

From these lines, we see traces of Mattisse in several of his paintings, such as "Notre-Dame", "Dance", "Music", "The Sorrows of the King", "Dream", "Odalisque", and "Sleeping Nude." Through these unrelated pictures the poet secretly installs a spectrum of danger and uncertainty: "the dangerous frontier of some unknown dreams" (7) "the rumors accumulated upon the pillows" (12), "the frightened velvets" (13), "little trauma" (14), "the treacherous looks by the bed side" (24), "the lying colors" (30), "screaming for help with massive red" (41), "a rented game within the dangling quilt" (45), "an enormous collapse under the pillow" (86-87).[14] The sense of being a disturbed "passer-by" (49) links these bits of danger from line to line, and sums up at "one house, one room, one bottle of nostalgia, one uncontrollable Matisse" (79-80). Interpreting Matisse, Ya Xian's suppressed and unutterable fears for his own nostalgia in the unstable cold war period between Taiwan and the mainland are released and leaked uncontrollably through the pages as the blood-red color over the canvas. The expressed nostalgia may cause real danger. The poet can only tolerate the present reality, the temporary inhabitation in Taiwan, as the degenerate tune (89), the filthy palette (90), the declining paradise (91), as if practicing copulation with the whore, a temporary, dangerous and despicable game.

The surrealist collage provides poets a mechanism to liberate the shattered and unorganized experience of the historical trauma. Ya Xian's strategy in his surrealist collage is to divert the audience's attention away from the center of the painting. Even though in Ya Xian's poem the speaker takes up a male gender position, but, different from what Mitchell describes, the speaker's envoicement in the Surrealist Collage Mode is not to feminize or to fix the visual objects through a masculine gesture; rather, the speaker takes up a feminine strategy with aleatory glances, selecting unrelated details from the corners on the canvas, avoiding the target and speaking about the absence of the painting in a circular and fluid exchange. The absence, the void, the shades of colors, becomes the atomic stimulus which triggers the poets's random enunciation. But this randomness, unlike the gaze-attracting Palace Museum, frees more violent longings for the past and hostility against the present which is suppressed and unmentioned in the text.

These two opposite modes of representation, the Palace Museum and the Surrealist Collage, the gaze and the glance, take opposite routes in dealing with the cultural Other: the gazer begins with a centripetal movement, prolonged, contemplative, but ending with a renouncement and disengagement; the glance moving around in a centrifugal manner, with a furtive or sideway look, whose attention is elsewhere, but is nevertheless caught up by the materialized blank space of the canvas, along with a hidden message of hostility, collusion, rebellion and lust.

IIIThe Ekphrastic Poets of the New-born Generation: Su Shaolian & Chen Li

When we examine the ekphrasis poetry of the second-generation diaspora, we find that the two modes of representation are taken over, and the implied textual and political "otherness" is transformed into a different context. The acute sense of alienation from China and the modernist pang of cultural homelessness experienced by the first-generation diaspora are changed into nightmarish and absurd portrayal of the historical trauma, and even into a carnivalistic parody of the diversity of new origins and identities in Taiwan.

In Su Shaolian's reading of Chagall's paintings in "Chagall's Dream" (Xiakaer de Meng"), the "red night sky" he sees on the canvas, "La Nuit de Vence" for example, has become "the cover of the closed notebook of his own childhood," indicating both the 228 event and the communist-phobia period, the White Terror Period, a passage of the silenced past history shared by all Taiwanese, which does not speak up even to himself when he is grown up. The red motif on Chagall's paintings is a complex mingling of the artist's nostalgia for his Russian hometown, childhood, families, and later his deceased wife, with feelings of warmth, traumatic, hurt, fear, and anger; this red motif has been condensed by Su as the alarming signal of the political terror he experienced in his childhood. Su's surrealist method is even more obtrusive when it comes to his reading of the map in "A Portrait of Earthquake" (ˇ§Dizhentu") :The mainland is a dismembered human body; Shandong peninsula, a segment of the leg, stranded over the beach of Penghu island; Mt. Huangshan, the crooked fingers of the palm, fallen into the black ditch of the Taiwan Straits; the back of the Yungui Highland is disjoined and thick blood overflowed; the Long Wall of the Yellow Land Plateau is pushed into the Bohai Harbour; the landscape of Sanxia is hanged up-side-down at the edge of the Suhua Road at the east coast of Taiwan. (ˇ§Dizhentu")

The topographic differences on the map redirect the poet's nightmarish memories. The dismembered and dislocated body parts not only metaphorically reflect the poet's views of the state of affairs in China, but also his testament of the bombarded and disintegrated mainland transplanted into Taiwan. The names of the places in China reappear as street names all over Taiwan and the diaspora from different provinces scatter over different corners in Taiwan. The transplantation, to the poet, is a bizarre and surrealist one.

The map of Taiwan shows an even scarier look to the poet:

Ah! Taiwan is a scorched sweet potato, smoking! The land at the north of Tanshui River is drifted away to the islands of Liuqiu; the presidential palace is buried underground, crushed and disappeared; the land of the south of Zhuoshui River is floated away to Philippine; Lanyu rises up from the sea and become the highest point of Taiwan; Dajia River is stretched wide, and the water of the Taiwan Straits flow through the Pacific Ocean. (ˇ§Dizhentu")The land of Taiwan is dispersed as diversely as its political groups: the native aboriginal who have been driven to the mountains, the early immigrants who speaks "Taiwanese," the late 1949 immigrants who are addressed as "the mainlanders" or "wai-sheng-ren," the second generation of the mainlanders who do not share the historical burdens of China, and the younger generation of the "Taiwanese" who do not speak Taiwanese. Like Ya Xian, when speaking of the island, the poet in Su Shaolian's poem situates himself at a drifting and floating position in the air.

Chen Li replaces the homelessness and dislocatedness with his re-affirmation of the diverse identities. In his post-modern surrealist revision of Miro's "The Dog Barking at the Moon" ("Feiyue zh quan"), Chen Li distorts the icons on the canvas even more drastically. [15]The moon is pasted on the sky like a stamp obscured by the postmark.

We write letters with ball point pens of starlight and mail them

To God, who lives north of the air-raid shelter?

And two express conductresses in red skirts and red hats

Push the pushcart by and ask if he'll buy some medicine.Of course it's bitter,

Still he sends us a family photo:

The war-fostered colonel, the black-skinned procuress,

Tomcat Gigi, the unmarried old maid A-lan --

They are all there, on the platform of time,

Facing a dog barking at the moon with wide-open eyes. (Ll. 16-26)[16]The effaced warring history of the shift from mainland to Taiwan, and the effects that it has brought to people, are jammed in the family photo; the major brought up by wars, the dark-faced aboriginal at the whore house, the old maid, all emerge through the darkness on the canvas, and line up on the platform of the railway station of time. The black background in Miro's painting becomes for Chen Li a figure of the Taiwanese collective unconscious, with suppressed or forgotten memories. Chen Li calls his audience's attention to the black space, summons up the traces of the forgotten memories, and he seems to be able to see such family photos from every moon-stamp he sees, as if opening up a stamp album:

We open the stamp album, suspiciously searching out

Seemingly familiar cries.

Maybe that's what they call family reunion. (Ll. 28-30)The "family reunion" Chen Li ridicules but acknowledges is an accepted fact of Taiwan: a reunion of all people. This coincident of the "reunion" is caused by the wars which have shaped the Taiwanese collective memories of the past. These people speak different languages; carry different past, taking up different positions, but all standing on the same platform as travelers. The tone of disengagement echoes that of Ya Xian and Su Shaolian. In a later poem "Tightrope Walker" ("Zousuozhe" 1995), the poet assumes a similar position of uncertainty and an anxious tone: "with a slanting bamboo cane, with a fictitious pen" (36-37), the poet collected laughter fell upon the air, "all the joke system of all continents and subcontinents, interwoven in your body like tributaries" (13-15).

The intent to reconstruct the Taiwanese identity has led Chen Li to move away from the surrealist laugh to the mode of the gaze, to build up an effigy at the museum and treat it as a sacred object. Taiwan for Chen Li has long been cut from the mainland and has been presented by the poet as an autonomy which can speak to the world through his needle-like pen.On the world map which is reduced to one over forty million,

Our island is an imperfect yellow button

Lying loose on a blue uniform.

......

My hand is holding my needle-like existence:

Threading through the yellow button rounded and polished by

The people on the island, it pierces hard into

The heart of the earth that is behind the blue uniform. (Ll. 1-3, 27-30)He also takes the reader to look at the firemen in the photo at the memorial hall and imposes on the figures different languages: Japanese, Taiwanese, Hahka, Ahmei, and Atayal.

The fire engine made in Japan did not choose the language to put out the fire.

He speaks Japanese. He speaks Taiwanese.

He speaks Ahmei, Atayal, and Hahka.

But the silent history understands only one voice:

The voice of the victor, the voice of the dictator, the voice of the winner. ("Zhaohe Jinianguan," Ll. 28-32, my translation)Like in his other poems, such as "Green Onions", "Water Baffullo", "Hualian Street, 1939", "Formosa, 1661" Chen Li intentionally "searches and reorganizes the image of the island and seeks the echoes of the history" (The Edge of the Island 205).

The narratives the Taiwanese poets add to the ekphrastic images reveal a progressive alienation of Taiwan from China, even a gradual shift into the search for new but diversified identities. The framed plastic objects in the Palace Museum attract the poet's gazes and channels his longing to return to the cultural homeland, but it also reminds him of a conscious separation from the past, so as to reorganize the chaotic memory and to rebuild his own identity. Through the poet's masculine renouncement, the cultural Mother is worshiped, housed in the Palace Museum, but at the same time stilled, feminized, and silenced. In the surrealist collage, on the other hand, strangely we see the poets exercise a feminine disorientation from the gazed object and present the visual objects in a wild, disordered and fluid manner of scattered glances and the objects is put aside with an anxious laugh. But, from underneath the irrational collage emerges a more violent longing to return. For the second-generation diaspora, the dismembered map of Taiwan is a restructured Taiwanese experience, taking different people onto the island, while the urge to remold a new identity calls for a second wave of Palace Building. The building process is a self-representation, summoning voices from the history of Taiwan, embracing immigrants from different generations, affording no space yet for any distancing gesture.

ˇ@

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. London: Collins/Fontana, 1973.

Bryson, Norman. "The Gaze and the Glance" in Vision and Painting: The Logic of the Gaze. New Haven: Yale UP, 1983.

Carter, Paul. Living in a New Country: History, Traveling and Language. London: Faber & Faber, 1992.

Chambers, Iain. Migrancy, culture, identity. London & New York: Routledge, 1994.

Chen, Fangming. "The Returned Prodigal Son: On the Transformation of Yu Guangzhong's Poetic Vision". The Phoenix in Flame: A Collection of Critical Essays on Yu Guangzhong's Works.. Ed. By Huang Weiliang. Taipei: Chunwenxue Publishing Co., 1979. Pp. 396-408.

Chen, Guying. Such a Poet: Yu Guangzhong. Taipei: Da Han Press, 1977.

Chen, Li. Intimate Letters: Selected Poems of Chen Li 1974-1995, translated by Chang Fen-ling, Taipei: Bookman Books LTD., 1997.

Chen, Li. "Yaowu," "Xiaochou Bifei de Beige,," "Moshush de Qingren," "Feiyue zh Quan," in Qingmishu. Hualian: Hualian Culture, 1992. 26-27; 41-43; 61-62; 245-247.

__________. "Zhaohe Jinianguan," "Daoyu Bianyuan," in Jiating zh Lyu. Taipei: Maitian Publisher, 1993. 151-153.

__________. "Zousuozhe," "Hualian Harber Streets, 1939," "Momosa, 1661," "Daoyu Feixing," in Daoyu Bianyuan. Taipei: Huangguan Wenxue Publisher, 1995. 139-142; 181-187; 188-193; 199-201.

Davidson, Michael. "Ekphrasis and the Postmodern Painter Poem." Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 42.1 (1983): 69-79.

Giry, Marcel. Le Fauvisme. (1981) trans. by Li Songtai, Taipei: Yuanliu Publisher, 1992.

Hagstrum, Jean. The Sister Arts: The Tradition of Literary Pictorialism in English Poetry from Dryden to Gray Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1958.

Hall, Stuart. "Cultural Identity and Diaspora." Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994. 392-403.

Heffernan, James A. W. "Ekphrasis and Representation" in New Literary History. 1991, 22:297-316.

Hollander, John. "The Poetics of Ekphrasis." Word & Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry 4.1 (1988): 209-219.

Jian, Zhengzhen. "Yu Guangzhong: The Phenomenal World of Exile" in The Sparkling Pen of Colors: A Collection of Critical Essays on Yu Guangzhong's Works 1979-1993.. Taipei: Jiuge Press, 1994. Pp. 88-124.

Krieger, Murray. Ekphrasis: The Illusion of the Natural Sign. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Krieger, Murray. "The Ekphrastic Principle and the Still Movement of Poetry: Or, Laocoon Revisited." The Play and Place of Criticism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1967. 105-28.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay On Abjection (1980). trans. by Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Kristeva, Julia. Strangers to Ourselves. trans. by Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

Liu, Joyce Chi-Hui. "Palace Museum vs. the Surrealist Collage: Two Modes of Identity Construction in Modern Taiwanese Ekphrasis Poetry" (Chinese version) in Zhongwai Literary Monthly. December 1996, Vol. 25, issue 7, 66-96.

__________. "Surrealist Visual Translation: Reconsidering the Horizontal Transplantation' in the Modernist Movement of Taiwanese Poetry," (Chinese) in Zhongwai Literary Monthly 24:8 (1996): 96-125.

Liu, Qiudi. "The Evolution of Yu Guangzhong's Poetic Style" in The Sparkling Pen of Colors: A Collection of Critical Essays on Yu Guangzhong's Works 1979-1993.. Taipei: Jiuge Press, 1994. Pp. 45-87.

Massey, Doreen. "Double Articulation: A Place in the World." in Angelika Bammer. Ed. Displacements: Cultural Identities in Question. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994. 110-122.

Meltzer, Fran‡oise. Salome and the Dance of Writing. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1987.

Meyer, Kinereth. "Ekphrasis and the Hermeneutics of Landscape." American Poetry 8 (1990): 23-36.

Mitchell, W. J. T. "Ekphrasis and the Other" in The South Atlantic Quarterly 91:3, Summer 1992. pp. 695-719.

Mouffe, Chantal. "Radical Democracy: Modern or Postmodern?" Universal Abandon?: The Politics of Postmodernism. Ed. Andrew Ross. Minneapolis: U of Minnestora Press, 1988. 31-45.

Murray, Linda. The High Renaissance and Mannerism. London: Thames and Hudson, 1967. Reprinted 1990.

Riffaterre, Michael. "Syllepsis" in Critical Enquiry. VI, 1980, pp. 625-38.

Said, Edward. "Reflections on Exile." in Russell Ferguson, Martha Gever, Trinh T. Minh-ha and Cornel West. Eds. Out There, Marginalization and Contemporary Cultures. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990.

Su, Shaolian. "Xiaokaer de Meng," "Dizhentu," in Poetry Collection in 1994. Taipei: Xiandaishkanshe, 1994. 9-14.

Worton, Michael. & Still, Judith. eds. Intertextuality: Theories and Practices. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press,1990.

Wumingshi. "Sheyi yu pinglei--on Ya Xian" in Yiushi Wenyi.1994.6: 82-90.

Xi, Mi. "From Modern to Contempory--On Miro's The Dog Barking at the Moon.'" Chung Wai Literary Monthly. 23(3): 6-13.

Ya, Xian. "To Mattisse," in Yaxian Poetry. Taipei: Hongfan Books, 1981. 231-238.

Yan, Yuangshu. "The Modern Chinese Consciousness in Yu Guangzhong" inThe Phoenix in Flame: A Collection of Critical Essays on Yu Guangzhong's Works.. Ed. By Huang Weiliang. Taipei: Chunwenxue Publishing Co., 1979. Pp. 69-89.

Yip, Wai-lim. "Zai Jiyi Lisan de Wenhua Kongjian li Gechang" in Zhongwai Literary Monthly 23.3(1994): 74-104.

Yu, Guangzhong. "Ditu," in Wangxiang de Mushen. Taipei: Chunwenxue Yuekanshe, 1972. 61-69.

__________. "Baiyu Kugua," "Tangma," in Yu Guangzhong Poetry 1949-1981. Taipei: Hongfan Books, 1981. 287-290; 304-307.

__________. "Huanghe" in Zhonghua Xiandai Wenxue Daxi: Poetry. Taipei: Jiuge Publisher, 1989. 191-193.

__________. "Zhongguo Jie," "Chin Yong" in Meng yu Dili. Taipei: Hongfan Books, 1990. 174-176; 180-184.

ˇ@

ˇ@

[1] Part of the paper was first presented in the conference of "Post-Modern China: Viewing Chinese Literature through a Global Lens," the Fifth International Conference of the American Association of Chinese Comparative Literatuure (AACCL), at the University of Georgia, April 19-21, 1996; the complete paper was later presented in the conference of "Globalization/Localization and Cross-Cultural Studies: The Chinese Paradigm," at Taipei, June 8-9, 1996. A longer version of this present paper has been published in Chinese, Zhongwai Literary Monthly. December 1996, Vol. 25, issue 7, 66-96. This project was funded by National Science Council (NSC84-2411-H-030-002).

[2] "Surrealist Visual Translation: Reconsidering the Horizontal Transplantation' in the Modernist Movement of Taiwanese Poetry," published by Zhongwai Literary Monthly 24:8 (1996): 96-125.

[3] For other discussions on Ekphrasis, see Krieger's "The Ekphrastic Principle and the Still Movement of Poetry: Or, Laocoon Revisited" (1967); Davidson's "Ekphrasis and the Post-modern Painter Poem" (1983); Meltzer's Salome and the Dance of Writing (1987); Hollander's "The Poetic of Ekphrasis" (1988); Meyer's "Ekphrasis and the Hermeneutics of Landscape" (1990); Heffernan's "Ekphrasis and Representation" (1991); Krieger's Ekphrasis: The Illusion of the Natural Sign. (1992) and W. J. T. Mitchell's "Ekphrasis and the Other" (1992).

[4] Yu Guangzhong's "Jade Mellon," "The Qin Clay Warrior," "The Tang Horse," Luo Fu's "Reading Chou Ying's Lanting Picture," Ku Ling's "At the Palace Museum," Sha Sui's "Walking over the Map of China," Chen Jiadai's "The Icy Cold Map" are some examples of the first group.

[5] Ya Xian's "To Matisse," Su Shaolian's "Chagall's Dream," Yang Ran's "Reading Magritte," Chen Li's "The Dog Barking at the Moon" are some examples of this second group.

[6] "The Gaze" and "The Glance" are terms I borrowed from Norman Bryson's article "The Gaze and the Glance" in his book Vision and Painting: The Logic of the Gaze. In this article, Bryson uses this pair of contrastive terms to dinstinguish the different modes of perspective in western paintings and Chinese paintings. Though this contrast may not be approapriate in discussing all Chinese paintings, I found it useful for me to pair off the different modes of perspectives in modern Taiwanese poetry.

[7] The theme of nostalgia is a marked motif which recurs throughout Yu Guangzhong's poems from the 1950s to the 1980s. The poet's sense of "Chineseness" and of "home" in his exile in Hong Kong or Taiwan is the issue critics discuss and debate about the most. See Yan Yuanshu, Chen Guying, Chen Fangming, Liu Qiudi, Jian Zhengzhen.

[8] "When I Lay Dying" ("Dang Wo Si Shi" 1966) and "The Beat Music" ("Qiaodayue" 1966) are two examples.

[9] The milk motif also recurs in many of Yu's homeland poetry, such as the milk of the Yellow River in "Yellow River" ("Huang He"), of Yangzi River in "Eastward Runs the River" ("Da Jian Dong Qu"), and the thirst for the milk is the thirst for the homeland.

[10] Other map-reading poems are illustrative in this respect, for example, Ya Xian's "My Soul" ("Wode Linghun"), Sha Sui's "Walking over the Map of China" ("Zouguo Zhongguo de Ditu") and Chen Jiadai's "Icy Cold Map" ("Bingleng de Ditu").

[11] The tiny walnut boat admired by foreign tourists in Ku Ling's "At the Palace Museum" ("Zai Gugong"), or the old man as a traveler in Luo Fu's "Reading Chou Ying's Lanting Picture" ("Guan Chou Ying Lanting Tu"), all denote a look of difference and alienation.

[12] The surrealism was welcomed wholeheartedly by modern Taiwanese poets during the politically tense period. Such as Luo Fu, Ya Xian during the 1960s, and Wai-lim Yip, Da Huang, Guan Guan, Xin Yu, Chu Ge, Zhou Ding, Shen Linbing, Zhang Mo, Bi Guo, through the 1970s (Luo Fu's "Surrealism and Chinese Modern Poetry"). This surrealist mode even extends its influence down to the post-modern age and manifest through poets of the younger generation, such as Su Shaolian, Chen Li. For further discussion on the Surrealist Movement in Taiwanese literature, please see my paper "Visual Translation of Surrealism: On the Horizontal Transplantation' of Taiwanese Modern Poetry," Chongwai Wenxue, 24.8 (1996, 1):96-125.

[13] We can point out a list of paintings by Mattisse which correspond to Ya Xian's verbal allusions: "Odalisque," "Harmony in Red," etc.

[14] This unutterable and distorted fears populate the poems of the surrealist group during the 1950s and 1960s. One explicit example can be found in Luo Fu's "Drinking Song" ("Yinjiuge").

[15] Xi Mi has discussed the post-modern nature of this poem: temporalized spatial experience, the fictitiousness of the individual, the flow of history, and the collective replacing the individual (Xi Mi 10-12). Xi Mi did not comment on the historical context which Chen Li installs in this poem.

[16] The following passages of Chen Li's poems, unless differently specified, are taken from Intimate Letters: Selected Poems of Chen Li 1974-1995, translated by Chang Fen-ling, Taipei: Bookman Books LTD., 1997.