Re-staging Cultural Memories

on Contemporary Taiwanese Theatrical Stage:

Wang Qimei, Stanley Lai, and Lin Huaimin

���媩

Copy RightGraduate Institute for Social Research and Cultural StudiesJoyce C. H. Liu

National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan

Published in East Asian Cultural and Historical Perspectives: History and Society, Culture and Literature. Ed. By Steven Totosy de Zepetnek and Jennifer W. Jay. Alberta, Canada: Research Institute for Comparative Literature and Cross-Cultural Studies, University of Alberta, 1997. 267-78.

I Cultural Memories and Performative Rhetoric on Stage II Taiwanese Identity as an Orphan III The Blank Spot (Liubai) of the Sign: Stan Lai's Missing/UtopiaIV The Half-transparent Screen on Stage: Lin Huaimin's Signs of the Chinese

V The Sign of the Chinese as Performative Tropes of Interstices

I Cultural Memories and Performative Rhetoric on StageII Taiwanese Identity as an Orphan

Adopting Richard Schechner's definition of performance as "restored behavior," Joseph Roach in his study of the culture and performance in New Orleans suggests that "the concept of restored behavior emerges from the cusp of the art and human sciences as the process wherein cultures understand themselves reflexively and whereby they explain themselves to others" (218). He further points out that "literature itself (and not just dramatic literature) may be understood as the historic archive of restored behavior, the repository and the medium of transmission of performative tropes" (218). Roach's study leads him to discuss the paradoxical relations between the act of improvisation and the cultural memory. Ritualistic repetition of restored behaviors re-enacts and stabilizes the past through deliberately formulated and stylized steps and gestures, while improvisation and its unbidden creative eruptions, Roach argues, instead of erasing or negating memory, actually celebrate cultural memories. For Roach, the disclosure of suppressed improvisations is a "method of cultural critique" (222).

In my present paper, I would like to follow the line of thinking discussed above and re-examine contemporary Taiwanese theater and analyze the theatrical signs of cultural memories through which the directors re-stage and re-inscribe the past in order to construct new cultural identities. In recent decade, as we can see in all cultural forms in Taiwan, including public forums, scholarship, literature, arts, drama, and even dance, there has been an on-going process of self-conscious construction of a new Taiwanese identity; along with this quest movement is a clear shift from the narrative of the monolithic Han origin to that of a hybridized local subjectivities. I hope to demonstrate through my analysis of the production and the reception of the performative texts on contemporary Taiwanese theatrical stage that the effort to cut off from the traditional narrative of the Han identity is especially obvious for the second generation Chinese Diaspora artists in Taiwan. These artists are mostly in their forties, such as Wang Qimei, Stan Lai and Lin Huaimin, whose parents were born in China and were forced to move to Taiwan in 1949. Moreover, Wang Qimei, Stan Lai and Lin Huaimin are all western-trained intellectuals and carry with them both the avant-garde mind as well as the burden of the Chinese culture and history. What makes their situation more complicated is that they also face the confusion of national/ethnic identity as a Chinese or a Taiwanese. Throughout their formative years in Taiwan, they considered themselves Chinese, but as soon as they left Taiwan they were addressed as Taiwanese, either in China or in other place of the world. When they returned from their graduate education in the West and tried to re-adjust their "Taiwanese" identity, they were faced with the doubtful looks from the local "Taiwanese" and challenged with their Taiwanese dialect of mandarin accent.

The aim of this paper is to discuss the staging and the performance of the construction of national/ethnic identities in contemporary Taiwanese theaters, and the complex problems underneath the surface of the performative rhetoric. I shall take Wang Qimei's "orphan plays" as a theatrical emblem to show the collective narrative of the historic impulse in recent Taiwanese cultural activities to re-construct a new cultural identity, and examine the problematic in the staging of such historic narrative. I shall then take the visual icons staged by Stan Lai and Lin Huaimin for further analysis and discuss how on the one hand their stage also reflects the same collective narrative impulse of identity construction, while on the other hand they manage to stage the gaps of cultural identification through theatrical signs of interstices, signs of ancient China. I shall show in my following discussion that the so-called "improvisations" practiced by Wang Qimei, under the influence of the West, paradoxically bring out a set of culturally pre-conditioned behaviors and historically-coded signs which correspond to the collective orphan-complex of the Taiwanese's self-representation. On the contrary, the highly stylized physical movements and visual signs employed by Stan Lai and Lin Huaimin, especially the intertextuality they employ in dialogue with ancient Chinese texts, speak on the surface to the archive and the repository of Chinese cultural memories shared by the audience, but reveal a conceptual interstices and incongruity as well as an unsettling critique of the cultural past. Moreover, the increasing presence of the ambiguous androgynous male bodies on Lin's stage, and its quotations from gay writers' literary works, such as Qu Yuan's Nine Hymns, Chao Xueqin's Dream of the Red Chamber, and Herman Hesse's The Wanderer's Song, further upset the male-dominated hierarchical cultural structure of ancient China. Theater has become a site for these artists' meditation, recollection, envisioning, and for ideological and gender struggles in the process of their identity construction.

�@

In a symposium on the relocation of Taiwanese Literary History, held at Taipei in October 1995, a contemporary Taiwanese woman writer Ping Lu remarks, in reaction to the debates on the "origins" of Taiwanese literature:[1] "If we open up the world map and examine the relation between Taiwan and mainland China, would the island grow bigger, or smaller? Would the island extend an arm and reach the mainland, as a peninsula? Or would the globe get compressed and result in the island's drifting away from the mainland for good? . . . . All possibilities are laid out in the imaginary web woven in Taiwanese literatures" (54). This pictorial statement paradoxically and yet characteristically illustrates the ambiguous and complex relations between Taiwan and China. The proximity of the geographical positions and the several movements of immigration in history seem to dictate some sort of blood relations. The size contrast between the mainland and the small island, moreover, even seems to impose a parent-child bond. The link maintained by the Taiwan Strait, however, presents itself as an existential question mark: does this flow of current hold the two entities, or does it separate?

In recent history, the ownership of Taiwan government has been drastically turned over twice, through military force and high political oppression, first from the hands the Chin government to that of Japan in 1895, and then from Japan to the KMT government which retreated from the Mainland in 1945. Wu Zhuoliu's novel The Orphan of Asia, written in the year before the end of the Second World War and the Japanese Colonial period, reflects the ambiguous cultural identity of the Taiwanese jammed between Japan and China, and the anxiety of being disowned by the Mother Country. Peng Ruijin has pointed out that the "Orphan consciousness" revealed in Wu Zhuoliu's novel has deeply touched the sensitivity of all Taiwanese, and even become the name which represents every Taiwanese (1985: 94). Li Qiao's The Trilogy of the Cold Nights, written during 1970's, also depicts the history of Taiwanese under the Japanese occupation, and a strong urge of a child wanting to return to the Mother. But, in the previous novel, the Mother Country is China, whereas in the later one, the "Mother" image has been transformed into the mountains of Taiwan. The search for the roots, likewise, has been diverted from the Central Land to the land on the island.

The desire for recognition by China revealed in the "Orphan Complex" through Taiwanese literary imagination, we have discovered, has been changed into an urge for the re-construction of a new identity in the 1980's and 1990's. Wang's theatrical statement in The Orphan of the World, premiered in 1987, is a continuation of the rise of local Taiwanese awareness starting from the 1970's. Because of the unfavorable political conditions Taiwan government faced, Taiwanese intellectuals began to search for traditional Taiwanese cultural symbols which could represent the Taiwanese experience. Jiang Xung, a Taiwanese art critic, pointed out that this relapsing fever in the 1970 involves not only the literary activities, but also different forms of arts, such as Shih Weiliang's local ballads, Hansheng Magazine's introductions of local folk arts, Xuengshih Art Journal's praises of Hong Tong, and the Cloud Gate's dance of the local ritual dance Bajiajiang (1977: 67). Kaohsiung Incident [2] in 1978 was a heavy blow on most Taiwanese and the after effect was the resistance against the political terrorism of the KMT government as well as the growth of the keen awareness of the local voice and of human right. The debates over the "Chinese consciousness" and the "Taiwanese consciousness" during the 1983 and 1984 further crystallized the polemic of the two magnetic axis in the Taiwanese identity construction (Zhang 11). Thomas B. Gold (1994) also points out that the "quest for a unique Taiwan identity" began early in the mid-1970's, along with Taiwan's "increased diplomatic isolation and the rise of the tangwai, the dissident party" (61). He lists several central themes which are shared by contemporary artifacts in Taiwan, including fiction, music, film, dance, theater, and scholarship: the awareness of rootedness in this place, nostalgia for local folk arts and architecture, a flood of publications on Taiwan's history, and political awakening of the general public (61-64). Gold concludes that, in the 1980's and the 1990's, "defining Taiwanese identity is still a process at the stage of rediscovering a history comprised of a diverse array of components, but it has become a conscious project" (64).

The Lifting of the Martial Law in 1987 was a symbolic act which concretely indicates the transition of the KMT period to the local Taiwanese voices. After the Lifting of the Martial Law, more people are involved in eager and public projects to reconstruct local cultural identity. The theatrical articulation of differences in Wang's work is representative because it echoes the diverse voices and perspectives in the moment of transformation in Taiwan before and after the Lifting of Martial Law in 1987. We also observe a gradual shift of the re-construction of the national identity and the formulation of the historicity of the past from the "pure blood" narrative, either that of the pure Central Land Han Origin or the pure "Taiwanese" Origin, to the "hybridity" narrative.[3] From the act of protest to the act of disengagement, there is a process of the growth of the Taiwanese voices, and a shift from the monolithic identity to the hybridized identities, from national subjectivity to community subjectivities.

In The Orphan of the World, the audience sees clearly how the young female director Wang Qimei presents a painstaking effort in mapping the hybridized identities of the Taiwanese experience. Wang was born in 1946 in Peking, but was raised up and educated in Taipei. Wang received her BA in Chinese Literature from Taiwan University, MA in Theater from Oregon University, U.S., and she returned to Taiwan in 1976 and since then she has been teaching and directing plays in Taiwan. In the preface to the premiere of The Orphan of the World in May 1987, Wang writes: "we grew up and progressed with Taiwan; this is our home, our land, our concerns and everything" (1987:3). The subject matter of the Taiwan identity and the metaphor of the "orphan" are definitely an intentional borrowing, as Wang admits in an interview with Yang Xianhong, from Wu Zhuoliu's The Orphan of Asia and Li Qiao's The Trilogy of the Cold Nights (Yang 157). During the preparation period and the rehearsals, Wang required her actors and actresses read Wu Zhuoliu's The Orphan of Asia, Li Qiao's The Trilogy of the Cold Nights, and study Lian Heng's General History of Taiwan, the first history of Taiwan written in 1918, recording the lives of the aborigines, the early Fukien and Hakka immigrants as well as later social lives, laws and wars. Wang also required her actors and actresses read their own family histories from the earliest time through immigration to the present generation, and encouraged them to improvise stories of their own. [4]

The premiere was warmly received by the audience because, according to contemporary writers such as Ah Chen or Jiang Xun, this play provides a good education of the Taiwanese history for their students. Ah Chen says that this play speaks up with sincerity "all the suppressed or forgotten past of Taiwan and stirred deeply the wounds in the heart of most Taiwanese" (Ah Chen 169). From the premier in 1987 on, Wang has presented this play several times; touring through different cities and small towns in Taiwan, and each performance is a revision. Her revisions of the play, take The Orphan of the World 1992, the Branch Edition for example, inevitably involve the changes of perspectives and voices of different participating actors and actresses, from rural scenes to urban life, from fishing harbor to stock market, from family factory to monopolized chain stores, and from local theater-going to TV, violence and kidnaps. Wang even directed a "sister-play" to it, The Son of the Earth in 1989, treating similar subjects.

Wang's attempt is to replace the monolithic narrative of the history of the Han Culture from the Central Land with the acknowledgement of the local Taiwanese voices. She tries to recapture on stage the different cultural memories of the Taiwanese of the past 400 years. She starts from the dramatization of the linguistic differences of the tongues used on the island, aboriginal dialects, Hakka, Fukien, Mandarin, and Japanese. She also tries to make use of theatrical extra-lingual elements, such as music, lighting, stage sets, space, and the choreography of the body movements to reinforce the multiplicity of the Taiwanese perspectives. The play starts with the polyphonic choreography of several groups of dancers traversing across different corners on the stage, representing different aboriginal tribes--Beinan, Bunun, Atayal, and Tsou. The acoustic space is woven with four contrapuntal but harmonious aboriginal ritual music, Atayal's "Wedding Ritual Song," "Bunnun's harvest song, Tsou's "Ode to the Hero," and Beinan's "Youngster's Monkey Sacrifice." In the following scene, the audience sees three groups of people, the Hans, the Fukiens, and the Hakkas, reciting in different languages and tunes the classical texts of Santzh-jing and Han Poetry , the same cultural heritage which these people share.

Besides the sincerity of Wang's intention, however, critics also acknowledged with some grudge about the "thickness" of the intention and form in her orphan plays.[5] Wang's techniques of theatrical collective improvisation is obviously a training she learned in US, as other U.S.-trained Taiwanese directors did at that time.[6] The freedom and space Wang gives to her actors and actresses are actually a mirage because what are performed on stage are highly coded and programmed with the historical consciousness, along with which the audience sees the orphan mentality of the Taiwanese as well as Taiwan social and economic histories. What strikes the audience's interest the most in each revision of her "orphan plays" is the characters's compulsive recitation of Lian Heng's The General History of Taiwan. The excessive repetition of the spots of time of the historical moments reveals an obvious historic anxiety of the director, the actors and actresses, as well as the audience--to search for the roots, to tell the Taiwanese history, to justify her autonomy and to define her identity. Under such powerful beckoning, the ritualistic and mythical tone in the opening scene soon disappears into the background. The recitation of the Taiwanese history starts from the glacier epoch, the formation of the island, to the inhabitation of the aborigines, the Three Kingdom period, Yuan, Ming and Qin Dynasties, to the Dutch and Spanish colonial periods, the Japanese occupation period, the KMT immigration, the February Twenty-Eighth Incident, and finally to the contemporary Taiwan society. From the fourth scene to the tenth, the audience finds that there are around seventy-five entries of historical dates and events! Such compulsiveness and excessiveness work like a spell which paralyzes the stage and makes it a homogeneous space. The family histories supposedly improvised by the actors and actresses are rendered in homogeneous narrative mode and flatten the dept of performance. Even the ending of the play is handled in a linear and prophetic manner, foretelling the events related to Taiwan in the future. History is then fixated and fetishized. The entire stage is metonymically transformed into a history textbook. The forwarding motive does not derive from within the characters, but is superimposed by the imperative voice of history. The intention to create a hybridized subjectivities and a multiplicity of perspectives turns out to be structured by a monotonous linearity. The characters also appear to be tightly bound up by the collective orphan narrative, and hence are left with no space to imagine or to move around. This gap between the theatrical intention and the stage representation leads us to observe the paradox of intentional identity construction. The strong impulse to compensate the erased and forgotten past, to restore the cut root, unwittingly forms a mysterious magnetic field which draws all narratives towards one single purpose and hence suppresses the heterogeneous voices and perspectives which are supposed to be maintained in art works.

When we examine the works of the two other contemporary Taiwanese theatrical artists, Stan Lai and Lin Huaimin, it is not surprising that we also find obvious traces of root finding and identity construction in order to retell the history of Taiwan. But, there are moments of interstices in the re-staging and re-inscribing of the past, especially through visual signs of cultural memories, in which we find that the construction of identification is a complex matter and through which the stage becomes an intense space of performativity, a liminal space for the audience to re-organize their cultural identities.

�@

III The Blank Spot (Liubai) of the Sign: Stan Lai's Missing/Utopia

�@ IV The Half-transparent Screen on Stage: Lin Huaimin's Signs of the Chinese

In the theatrical works by Stan Lai and Lin Huaimin, in the 1980's, the audience sees continuous efforts to re-examine the Taiwanese collective cultural identities. The stage for them has become the "interstitial passage,�� in Homi Bhabha's term. Homi Bhabha discusses the concept of the "interstices" in the introduction to his book the location of culture, using Ren�e Green's metaphor of the stairwell as the "liminal space," and remarks: the "liminal space, in-between the designations of identity, becomes the process of symbolic interaction, the connective tissue that constructs the difference between upper and lower, black and white" (Bhabha 4). Fixed identifications are reinscribed; the past is restaged; various cultural temporalities emerge. These different terms of cultural engagement are enacted in a bodily and performative way on the stage to make way for a space for a cultural hybridity in which any assumed hierarchy would be questioned. More specifically, the reason which makes Stan Lai and Lin Huaimin different from Wang Qimei's historically homogeneous space is that Lai and Lin construct a stage of disjointed and transitional space. We can further discuss such difference of space by analyzing the signs of interstices which carry collective cultural memories as well as the interactive tension of political forces. The combat of ideological territories is particularly sharp right on the borderline where the conflicting and incongruous signs meet on stage.

Stan Lai's play Anlian / Taohuayuan (Missing / Peach Blossom Spring) offers a typical post-modern revision of the China myth. Stan Lai's parents were born in China and they moved to U.S. as ambassador in 1940's. Stan Lai was born in 1954 in Washington City, U.S. He moved to Taipei in 1966 with his family when he was twelve, finished his high school education and undergraduate training, received his BA degree in English Literature from Fu Jen University in Taiwan. During 1978 to 1983, he studied at UC Berkeley and obtained his doctorate degree in drama from Berkeley. Lai returned to Taiwan in 1983 and has been teaching and directing plays in Taiwan, like Wang Qimei, since then. Stan Lai's plays, such as This Was the Way We Grew Up, That Night We Performed Comedians' Dialogues, Yuanhuan Stories, The Journey to the West, and AnlianTaohua Yuan are all experiments in search of contemporary Taiwanese mind which is woven with the cultural impacts from the West, from Japan, as well as the entire cultural memories of the past history, especially the relations between China and Taiwan. Zhu Tianwen, a famous contemporary woman writer, observed Stan Lai's success: because of the common experience Lai drew from the public's everyday life and from their shared cultural memories, "each of the performances he presents has become a significance social activity carrying for every audience a sense of social participation and belongingness" (Zhu 13).

Anlian / Taohuayuan are literally composed of two plays, or the rehearsals of the two plays Anlian and Taohuayuan, on the same stage. Anlian is a modern stage melodrama, set in a hospital in Taipei of the 1970's, in which an old sick person Jiang misses and hallucinates the meetings with his young lover Yun whom he had been separated from during the chaotic warring time in mainland China in the 1930's. The audience soon finds that Jiang has been missing Yun all the years, after he settled in Taiwan in 1949, and even after he married a Taiwanese wife. Taohuayuan, a farce in classical theatrical style, presents a parodic version of the classical text Taohuayuan, a synonym for the utopia in Chinese, by Tao Yuanming (365-427) of Wei-Jin Period of the fourth century. In this play, the audience finds that the reason the fisherman Old Tao leaves home is because his wife Chunhua has an affair with Boss Yuan. The interpolating structure of these two plays, due to the mistake of the rehearsal schedule, makes each play a frame for the other, one interpreting the other and at the same time de-framing each other. The lines the actors and actresses speak in each play further form an unsettling dialogue between the two plays.

The huge backdrop for the place Taohuayuan, a traditional Chinese landscape painting, with a dream-like village among beautiful pink peach blossom trees, and the remote, mysterious and misty mountains located in the background becomes the visual translation of what Jiang in Anlian nostalgically misses all the years: the utopian young love, or the homeland, or China. The young love remains intact and immaculate in Jiang's imaginary construction. This is the same sentiments most Diaspora in Taiwan who were exiled in 1949 share for their homeland China. The trick Stan Lai plays with this visual interpretation of the utopian spiritual origin, the audience soon realizes, is that he leaves one spot on the backdrop blank. This blank spot, so called "Liubai," is a traditional Chinese painting technique painters love to use in order to leave some space untouched by the brush so that the objects on the canvas do not appear too crowded. But, in Lai's version, the blank spot turns out to be a meaningful visual icon of an interstices, a missing sign, or a sign which escapes the reader's interpretation. On the stage, the audience sees the stage hand physically paints and fills up the blank spot during the progress of the play. The meaning of "Taohuayuan," or of "China," becomes incomplete, with interstices, awaiting Taiwanese's re-interpretation.

Stan Lai skillfully inserts intertextual dialogue with the classical text Taohuayuan through making the actor Old Tao's quote Tao Yuanming's text while at the same time commenting on it and changing the meaning of the text. Old Tao, referring both to Taohuayuan and to the author Tao Yuanming, recites: "Passing by along the river, forgetting the distance on the way. . . . Forgetting! Forgetting! It's good to forget! Forget about Chunhua, forget about Boss Yuan!" (Scene 7) In forgetting about "Chunhua" and "Boss Yuan," Old Tao has dropped the two component parts in "Taohuayuan" and kept only "Tao," the author of the text or, as the sound of "Tao" suggests, escaping. But, who is the author of the current text? How to escape? The original text has been appropriated and broken into phrases of different meaning by Old Tao. Forget the original text, forget history, and forget the meaning assigned by the author, so as to create a new text.

Through the staging of Anlian, interacting with Old Tao's verbal re-interpretation of Tao Yuanming's text, Stan Lai's intention of a critical re-examination of the diaspora's nostalgic dream for the past, for China, becomes more obvious especially in the visual set-up in Scene 10. In this scene, the skyscape for Anlian, the Taipei city, is covered up by the beautiful scene of Taohuayuan, and the slides of Anlian are projected onto the huge classical landscape painting. This projection creates a weird effect of double vision: on the background of the peach blossom spring, the audience sees a series of pictures of Taipei streets, houses, buildings, from a telescopic view of the city to a zoom-up of the hospital, its interior, and then to the Z-Ray picture of Jiang's infected lung. The contour of the landscape painting and that of Jiang's lung on the X-Ray picture collide on the background, disjointed but yet harmoniously correspondent. The visual impact of this juxtaposition is unsettling; the audience sees the projection and introjections both ways: the city map of Taipei is superimposed by the memories of the past, the utopian land, and the street names of Taipei literally take up place names of China, such as Changchun, Jinan, Tianjing, Beiping, Nanjing, etc. People walk on the streets of Taipei as if traversing through places in China. This nostalgic mentality of the diaspora in Taiwan, according to Stan Lai, functions as a collective disease, structured and institutionalized, of people who breathe the same air and have the same infection.

The director of the play-within-the-play Anlien emotionally and sentimentally calls Jiang "the Orphan of orphans" (Scene 6). Born in Jiling, the north-eastern part of China, "under the Japanese bayonets, leaving his hometown and roaming from place to place," Jiang represents the generation of Chinese of the 1920's and the 1930. Most people spent their childhood and their youth amidst the bombshells, roving and drifting about, away from home. They were forced to exile to Taiwan, an unknown land, in 1949, leaving their homes and families behind, hoping that they can return one day. This nostalgia symptom is even acoustically transformed and permeated on the stage through the old Chinese songs of the 1930, such as Bai Guang's "Searching", "I'm a Piece of Floating Duckweed" or Zhou Xian's "When do you Return", sounding repetitively from the tape recorder, a recurring motif, in a subdued and flattened tonal quality.

Over forty years's separation, however, this nostalgic hope has become a disease, and then a slap on the face, and then a joke, because the younger generation do not share their memories, and also because the "Taohuayuan" is no longer the same. Even the young actress who plays Yun (the cloud?), Jiang's lost love, insists that it is impossible for her to be Yun, or to act out the ungraspable cloud-like memories which the director-within-the-play wishes to reconstruct. Can the Taiwanese retrace the route back to the "Taohuayuan"? According to Tao Yuanming's Taohuayuan, Liu Ziji from Nanyang heard of this Peach Blossom Spring and started out to look for the place but failed because he could not find the path. In Stan Lai's Anlian / Taohuayuan, a young woman breaks in and interrupts the rehearsals of both plays, claiming to have an appointment with "Liu Ziji" and insisting on looking for him, comically acts out the dislocatedness and the absurdity of this search.

What is the "Taohuayuan" to Stan Lai after all? "Taohuayuan" seems to suggest a land of unreality, in which Old Tao, Chunhua and Boss Yuan, all dressed in white, with handkerchiefs covering their eyes, play hide-and-seek cheerfully and innocently in slow motion. Chunhua and Boss Yuan in this "Taohuayuan" are played by the same actress and actor at Wuling, but they refuse to recognize Old Tao. The uncanny resemblance makes this dream land a mirror image of reality, an imaginary vision projected by the subject, while the persistent disavowal energetically maintained by the blind dream thoughts protects the gap from being bridged so that the dream can remain intact.

When Lai was working on his play That Night We Performed Comedians' Dialogue in 1984, trying to reconstruct the traditional Chinese folk art cross-talk, he went off to Japan for a two-week' break. On the streets of Kyoto, he fully experienced the gap between tradition and modern life. He said, "I spent one whole day taking pictures of the wooden floor in one old temple at Kyoto. The interstices on the wooden floor and on the wooden wall attract my attention, interstices formed through hundreds of years, interstices of different angles. I suddenly realized that such unwelcome interstices, after the passage of long years, have become natural and smooth, an integral part in the environment" (Soong 16). Cutting off the ties with history, changing the significations of a sign, and escaping from the fixed version of the text are the theatrical statements Stan Lai makes. For Stan Lai, tradition, as well as China, has to be kept as an incomplete sign, with a blank spot to be filled up each time during the performative act of interpretation. China, Lai suggests through this play, is a sign of an utopian past, a motherland, for most Taiwanese, but this sign has a blank spot in it to be rewritten, re-staged and reinscribed, and the unreal collective imaginary of "the China" has to be removed from the lung.

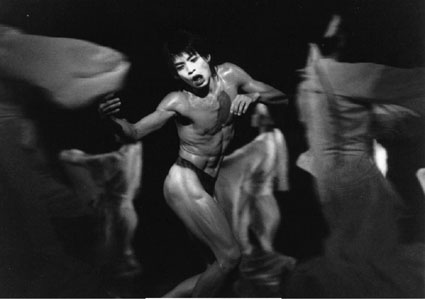

The inscription of the double vision, the traditional along with the post-modern, with a theatrical sign of interstices, can also be found in Lin Huaimin's Cloud Gate works. Like Wang Qimei and Stan Lai, Lin Huaimin is also the second generation of the 1949 diaspora from China. Lin was born in 1947 in the countryside of southern Taiwan, Jiayi, and received his higher education in Journalism in Taipei. He started out as a novelist, and studied in the Creative Writing Program of Iowa University for some time. But his interest in dance moved him to study dance first at Iowa University, then with Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham in New York. Lin returned to Taiwan in 1972 and started the Cloud Gate Dance Ensemble in 1973. The announcement they made when they established the Cloud Gate Dance Ensemble was: to compose music by Chinese, to choreograph the dance by Chinese, and to dance by Chinese for the Chinese audience. In Lin's works, the audience sees a site and a process of the struggles of different cultures shared by most Taiwanese. Martha Graham once said, "Art is the evocation of man's inner nature. Through art, which finds its roots in man��s unconscious - race memory - are the history and psyche of race brought into focus" (50). For Lin, the race memory is the hidden roots, the Chinese as well as the Taiwanese, which he needs to explore into through long years of experiments. But he also faces the drastic change of modern Taiwan which is taking place in his time. "Dance was no longer performing its function of communication. . . . Change has already taken place in man, was already in his life manifestations. While the arts do not create change, they register change" (Graham 50). The reason Lin's audience loves him is mostly because of the intermingling of the West, such as Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham and Paul Talor, with the "Chineseness," such as the long sleeves, long cloth, classical masks or costumes, but they also feel uncomfortable because they have to confront with the changes and shifts of the connotations of the "Chineseness" Lin has recorded in his dance language, and especially the increasing ambiguity of the androgynous male bodies on stage, and which the audience is not ready to cope with yet. In each piece, such as The Story of the White Snake, Little Drummer, Legacy, Dream of the Red Chamber, the Dreamscape, up to his latest work Nine Songs, the audience can see obvious visual icons borrowed from the traditional Chinese culture as the target of dialogue so as to resist, to disengage and to re-construct the Taiwanese identity.

V The Sign of the Chinese as Performative Tropes of Interstices

Within the frame of the traditional "Chinese" elements, moreover, the audience also notices a gradual shift to the relocation of the "Taiwaneseness" after the 1980, or, we should say, after his second trip to the U.S. and under the impact of the withdrawal of Taiwan government from the United Nation, and from the political stage. Lin started to re-examine his own roots in the land of Taiwan in Legacy in 1978. He asked himself: "Have we the artists employed the images of the current state of Taiwan as our cultural signs?" (qtd. In Ho, 11) Lin even says in 1987, on the fifteenth anniversary of the Cloud Gate, that "my fatherland is no longer the far away places recorded in the textbooks; it is Taiwan" (Lin Huaimin, "Fragments and Pieces," 245). Loyalty to the Central Land Culture keeps the Chinese diaspora from getting settled down in Taiwan, and both China and Taiwan exist in Taiwanese mentality as a dual belief system. In Shooting the Sun (1992), an ancient myth shared by the Ataya aboriginal tribes, Lin symbolically and ritualistically kills one of the two suns, two dictating political forces. It takes three generations of Taiwanese people to accomplish this theatrical ritual of termination, both for the audience and for Lin himself, of the dual loyal system.

Legacy (1978), Lin acknowledges, is an important transition point for him. During the preparation process for this performance, which is about the history of the early immigration from the mainland to Taiwan, Lin asks his dancers to study the histories of Taiwan, and to tell the stories of their own ancestors according to their family genealogy (Liu Changzhi, 25). Lin was convinced that through the dance the audience could ritualistically participate the spirit of unitedness and could be moved to generate new courage and strength to face the difficult political situation around 1978 (Wen Manying, 29-37). The eagerness and the commitment experienced by Lin at that time make the dance a rather realistic piece. We can see clearly that even up to The Dream of the Red Chamber in 1983 Lin's dance works are still monolithic in perspective.

Starting from the Dream Land in 1985, however, we start to observe an insertion of incongruous interstices in Lin's dance language. In Dreamscape, a half-transparent screen with Dunhuang Cave paintings projected on it separate the front stage and the back stage. Groups of dancers in modern suites or in ancient costume scatter in front of the screen as well as behind the screen. The audience thus observes the sharp contrast between the classical Chinese world and the modern Taiwan. This half-transparent screen metonymically becomes Lin Huaimin's interpretation of the Taiwanese condition: a sign visually links and separate the past and the present. Such visual motif of a bar is impersonated through a young man who dresses in modern suite and appears in various scenes, unassociated with the happenings of the scene. In the very beginning of the dance, this young man stands in front of a huge red gate, representing the Chinese history, wondering whether he should enter the gate or not. The function of this young man is clear: he erects a bar between the audience and the illusive ancient China on the stage. This disorienting visual icon recurs in Lin's later works, as the cyclist, the traveler, the roller skater in The Lottery and the Masquerade and in Nine Songs in 1993.

The Watery Sleeve, a characteristic dance language in traditional Chinese dance, also becomes Lin Huaimin's personal performative trope and powerfully executes the linking and separation with the Chinese past on Lin's stage. This motif of the long white cloth is actually derived from a conventional Chinese dance language - the "watery sleeve," which is a part of the traditional Chinese costume. In almost all of Lin's works, such as Han Shih, Qiyuanbao, Xingsu, The Tale of the White Serpent, Legacy, Dream of the Red Chamber, Dreamscape and Nine Songs, the audience can see the variation and transformation of the watery sleeve motif into heavy loaded sign of the Chinese. Early in Hanshi, in which Lin himself plays the tragic figure Jie Zhitui of the ancient China, Lin dances with a long strip of white cloth of about 30 feet and turns the solo into a duet between him and the white cloth, a dialogue with the Chinese history. In Hongloumeng, the long red cloth, which Jia Baoyu plays with but later was punished and tied up by it, symbolically represents the deadening confinements of the patriarchal and feudal structure of the Jia family, or of the Chinese culture. In Nine Hymns, The Lady of the Xiang River, with her tranquil gestures, her long white cloth, and her heavy expressionless mask, is a metaphorical figure of the feminized subjects awaiting the emperor's attention, representing the traditional Chinese culture of Confucian etiquette and of patient waiting. On the stage, the Lady of the Xiang River circulates and confines herself with the long white cloth, as most Chinese do by their cultural burden. Jia Baoyu, the only male nude in Hongloumeng, with his soft, tender and androgynous body, radically subverts the male-dominated patriarchal culture, a culture with too much cloth.

Nine Songs, a re-interpretation of Qu Yuan's (B.C. 329-299) poetic elegy Nine Hymns, is Lin Huaimin's manifestation of his farewell to China. Lin needs to quote and re-stage once again the ancient Chinese culture so as to purge himself of his nostalgia. The original text of Nine Hymns is composed of eleven sections; the first nine hymns are the chants by shaman priests and priestesses to incite the god to descend and take physical possession of themselves, the tenth hymn a lament for soldiers who have died for their country, and the eleventh, a fragment of a funeral dirge. Lin takes only six parts out the of first nine hymns and keeps the tenth and the eleventh. He apparently does not seek to re-construct this classical ritual, but merely borrows the form in order to exercise his own ritual of incantation and requiem. The central message, according to Lin, is that, after all the ceremonies and waiting, the God never arrives.

As a contrast to the Lady of the Xiang River, the priestess who starts and finishes the whole dance actually carries the force of revitalization. The dance of the priestess is a typical local Taiwanese ritual dance for fertility. The life force and the sexual connotation of her gestures come from her belly, and from the earth. The priestess even assumes the position of the mourning mother in the Pieta, cleansing the dead body of her sons, pacifying the souls who die for this land, including the martyrs in the revolutions of the 1911, in the Japanese occupation, in the 228 Incident, and in the Tiananmen Square Incident. The only solo in Nine Hymns, "Mountain Ghost," on the contrary, overturns the collective and ritualistic structure of the entire dance. The homoerotic message conveyed in Qu Yuan's original text in the chapter of "Mountain Ghost" is transformed into the desolate conditions and the desperate longing the artist tries to present.

The signs of the Chinese on stage have become the locus for theatrical artists to redefine their cultural status. Wang Qimei's orphan plays from 1987 to 1992 symbolically and symptomatically express the collective need to rebuild a new Taiwanese cultural identity, but paradoxically the ritualistic and historic impulses in the plays erase the diversity of voices on stage and make the theatrical space a flattened and homogeneous one. Stan Lai and Lin Huaimin obviously shared the collective need for a new Taiwanese cultural identity. Their stage, however, skillfully avoids the imperative collective voice and manages to present a more complicated version of the Taiwanese condition through employing signs of double articulation. Taohuayuan, Dunhuang Caves, Qu Yuan, Tao Yuanming, Nine Songs, Dream of the Red Chamber, the Red Gate, the White Cloth, and the Masks are all signs of Chinese cultural memories. Lai and Lin summon the memories of the past through re-staging these historical sings on stage, but at the same time they also manage to re-construct the signs and make them signs of incongruity and interstices, by inserting a blank spot in it or making the sign itself a half-transparent screen. The incongruity and interstices of the sign thus create a typical kind of double articulation, linking and separating the past and the present, China and Taiwan, and maintaining the co-relation of the two perspectives. For the second generation of Chinese diaspora in Taiwan, it is all the more urgent for them to re-define their Taiwanese identity. The highly androgynous male bodies on Lin's stage and the theatrical intertextuality with gay writer's verbal texts, further de-stabilize the phallogocentric and hierarchical inner structure of the Chinese culture.

�@

�@

�@

Ah Cheng. "One More Light, Please." The Orphan of the World. Taipei: Yuan Liu Publishing Inc., 1989. 169-170.

----------. "Hometown, with no Regrets." Preface to The Son of the Earth. Taipei: Donghua Publishing Inc., 1990. 5-12.

Chen Fangming. "Taiwanese Literature and Taiwanese Style over the hundred years--An Introduction to the New Taiwanese Literature Movement." Zhongwai Wenxue 23 (1995): 44-55.

Chen Zhaoying. "On the Localization Movement in Taiwan: A Study on Cultural History." Zhongwai Wenxue 23 (1995): 6-43.

Gold, Thomas B. "Civil Society and Taiwan's Quest for Identity." Cultural Change in Postwar Taiwan. Ed. by Steven Harrell & Huang Ch�n-chieh. Taipei: SMC Publishing Inc., 1994. 47-68.

Graham, Martha. "Graham 1937." The Vision of Modern Dance. Ed. Jean Morrison Brown. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton Book Company, 1979. 49-54.

Ho, Shengfen. "My Nostagia, My Love - - Interview with Lin Huaimin," Yiushi Monthly. Taipei, 1987(2): 8-12.

Jiang Xun. "OnThe Son of the Earth.." Preface to The Son of the Earth. Taipei: Donghua Publishing Inc., 1990. 13-16.

----------. "Get up and Take Greater Challenge." Xianrenzhang 1, 2 (1977): 67.

Lai, Stan Shengchuan. "A Drama Born Out of Nowhere: on Improvisation." Preface to Anlian/Taohuayuan. Taipei: Huangguan Publishing Inc., 1986. 4-11.

----------. Anlian/Taohuayuan. Taipei: Huangguan Publishing Inc., 1986.

Li, Qiao. "The Orphan is the Grandfather." The Orphan of the World 1992, Branch Edition. Taipei: Cloud Gate Dance Assemble Foundation, 1993. 3-8.

Lin, Huaimin, "Fragments and Pieces," in Passing by the Shouders. Taipei: Yuanliu Publishing Co., 1993. 235-248.

----------. "Loving this Land, Loving this People." The Orphan of the World. Taipei: Yuan Liu Publishing Inc., 1989. 167-168.

Liu, Changzhi. "Cloud Gate by the River," in Yunmen Wuhua (Cloud Gate Dance Stories). Taipei: Yunmen Foundation, 1993. 11-27.

Lin Ruiming. "The Studies of Taiwanese Literature under the Conflict of National Identity." Wenxue Taiwan (Literary Taiwan). 7 (1993): 14-32.

Ma Sen. "The Chinese Knot and the Taiwanese Knot in Taiwanese Literature." Lianhe Wenxue (United Literature). 89 (1992): 172-193.

Peng Ruijin. "Wu Zhuoliu, Chen Ruoxi, the Orphan of Asia." Wenxuejie 14 (1985): 93-104.

Ping Lu. "My Views on "Taiwanese Literature'". Symposium on Fifty Years of Literature in Taiwan. Published in Wenxun Monthly, 84:122�]1995�^�G52-55�C

Qiu, Kunliangr. "Loving the Spring Flowers Hard." The Orphan of the World. Taipei: Yuan Liu Publishing Inc., 1989. 147-150.

Roach, Joseph. "Kinship, Intelligence, and Memory as Improvisation: Culture and Performance in New Orleans." performance & cultural politics. Ed. by Elin Diamond. London and New York: Routledge, 1996. 219-238.

Soong, Yazi. "Stan Lai on the Memories of the Cross-Talk." That Night We Performed the Comedians' Dialogues. Taipei: Huangguan Press, 1989. 10-27.

Wang, Qimei (1987). "The Most Hurt and the Most Loved: Preface to the premiere of The Orphan of the World." The Orphan of the World. Taipei: Yuan Liu Publishing Inc., 1989. 3-6.

Wen, Manying. "Xinchuang in the Storming Rain" in Yunmen Wuhua (Cloud Gate Dance Stories). Taipei: Yunmen Foundation, 1993. 28-37.

Wu Micha. "The Dream of the Taiwanese and the Feburary Twenty-Eighth Incident--the Decolonization of Taiwan." Con-Temporary 87 (1993): 30-49.

Xin Dai. "Cold Eyes with Hot Tears." The Orphan of the World. Taipei: Yuan Liu Publishing Inc., 1989. 171-172.

Yang, Xianhong. "The Stage is Transparent." The Orphan of the World. Taipei: Yuan Liu Publishing Inc., 1989. 151-166.

Yie Shitao. "jie xu zu guo ji dai zh hou" ("Continuing the umbilical cord of the mother country--on the rise and fall of the Chinese consciousness and the Taiwanese consciousness in Taiwanese literature over the past forty years"), Zhongguo Luntan (Chinese Forum), 289: 135-145.

Zhang, Wenzhi. The Taiwanese Consciousness in Contemporary Literature. Taipei: Zili News Press, 1993.

Zhu Tianwen. "Another Play by Stan Lai." Preface to Anlian/Taohuayuan. Taipei: Huangguan Publishing Inc., 1986. 12-15.

�@

ENDNOTES********************************

[1]. The debates on the "origin" of Taiwanese literature, or the definition of the History of Taiwanese Literature, has been carried on since early 1980. The term "Taiwanese literature" was established during the debate on this issue during 1983-1984. See Zhang Wenzhi's discussion on this debate (44-46). For representative views on the "Chinese consciousness" or the "Taiwanese consciousness" in Taiwanese literature, please consult Yie Shitao's"Continuing the umbilical cord of the mother country--on the rise and fall of the Chinese consciousness and the Taiwanese consciousness in Taiwanese literature over the past forty years", Lin Ruiming's "The Studies of Taiwanese Literature under the Conflict of National Identity," Ma Sen's "The Chinese Knot and the Taiwanese Knot in Taiwanese Literature," Chen Zhaoying's "On the Localization Movement in Taiwan: A Study on Cultural History," and Chen Fangming's "Taiwanese Literature and Taiwanese Style over the hundred years--An Introduction to the New Taiwanese Literature Movement." The debates succeeding the latest two articles are still going on in recent issues of Zhongwai Wenxue.

[2]. The Kaohsiung Incident is a series of political suppression of the assembly of DPP and caused the imprisonment of many people, including the death of Lin Yixueng's family.

[3]. Chen Yingzhen is the leading figure among the critics who insist on the orthodox origin in the Chinese tradition, while Yie Shitao insists on the local consciousness. Please see Ma Sen's discussion on this debate. The concluding remarks in Wu Micha's "The Dream of the Taiwanese and the February Twenty-Eighth Incident--the Decolonization of Taiwan" is typical of the "pure blood theory" on the Taiwanese's side: "After the distortion of the colonial policies over the long period of time (nearly a hundred years), it requires tremendous efforts by Taiwanese to restore the authentic Taiwan" (46). Qiu Guifen's studies, such as "We are all Taiwanese" and the rest, are representative of the discourse of the post-colonial hybridization of identities.

[4]. During the rehearsals of his Xin Chuan in 1978, Lin Huaimin had used this technique to have his dancers study the history of Taiwan and the genealogies of their family histories (Liu 25).

[5]. Contemporary writers, artists and critics, such as Ah Cheng, Xin Dai, Lin Huaimin, Jiang Xun, Li Qiao, expressed their appreciation of Wang's contribution and devotion to Taiwan, while Qiu Kunliang pointed out the "thickness" of the historical allusions in this play.

[6]. The Berkeley trained Stan Lai, who returned to Taiwan in 1983, admitted that his strategy of collective improvisation was borrowed from Amsterdam Werkteater (Lai "Preface" 8-9). Wu Jinji's Lang Ling Dramatic Group is another example of the experimental theater in the 1980's.