側記|Film Screening and Discussion – State of Statelessness

2025-10-13

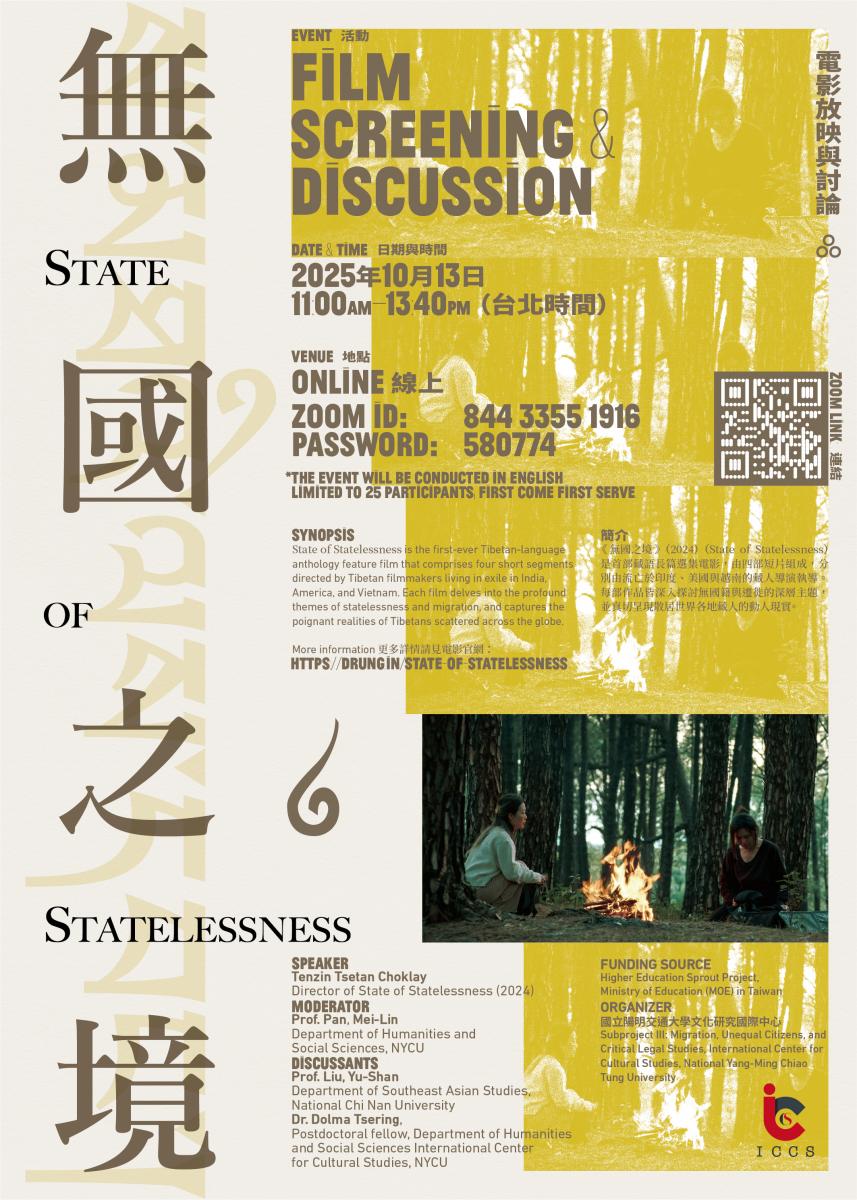

Topic | Film Screening and Discussion – State of Statelessness

Date and Time | October 13, 2025 11:00 - 13:40 Taipei Time (GMT+8)

Speaker | Tenzin Tsetan Choklay (Director of State of Statelessness(2024) )

Discussant |

Prof. Liu, Yu-Shan, Department of Southeast Asian Studies, National Chi Nan University

Dr. Dolma Tsering, Postdoctoral fellow, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, International Center for Cultural Studies, NYCU

Event Info | LINK

Event Photo | LINK

Reported by|Dolma Tsering

Sub-project|Subproject III: Migration, Unequal Citizens, and Critical Legal Studies

Convener|Joyce C.H. Liu, Yu-Fan Chiu, Mei-Lin Pan

As part of Sub-Project III, which examines the politics of unequal citizenship, the International Center for Cultural Studies (ICCS) organized a screening and discussion of the Tibetan-language anthology film State of Statelessness on 13 October 2025. The event formed part of ICCS’s ongoing commitment to engage with questions of citizenship, mobility, and identity formation in transnational and postcolonial contexts. State of Statelessness, the first-ever Tibetan-language feature film anthology, directed by four young Tibetan filmmakers, articulates the affective dimensions of statelessness. Composed of four interlinked narratives, the film presents the lived experiences of Tibetan exiles across diverse geographical and cultural settings, covering themes of family separation, ecological continuity, fluid belonging, and the intergenerational transmission of identity.

Overview of the four films

The first story situates statelessness within an ecological imaginary, following a Tibetan exile in Vietnam who finds belonging through the Mekong River, a transboundary flow that originates in Tibet and concludes in Vietnam’s delta. A conversation about China’s dam construction in Tibet and its implications for downstream countries like Vietnam captures the shared vulnerabilities of displacement, power fragmentation, and marginalized communities. The second story explores familial dislocation through the story of two sisters whose lives diverge as a result of migration and legal precarity. What initially appears as a tale of relocation gradually unfolds into a meditation on betrayal, guilt, and the erosion of kinship under the conditions of statelessness. The film exposes how forced mobility reconfigures emotional landscapes and kinship ties. The third film delves into the intricate social and emotional dynamics of a stateless Tibetan couple in India, illustrating the tension between the aspirations of one partner to migrate to the United States and the reluctance of the other to leave India. This conflict is set against the backdrop of the precarious legal status of Tibetans in India, highlighting the psychological, cultural, and existential challenges faced by stateless individuals navigating the complexities of displacement, identity, and the uncertain future that comes with living in a state of legal limbo. The fourth segment, directed by Tenzin Tsetan Choklay, centers on a family that migrates from India to the United States. It captures the affective pull of home and the persistent desire to reconnect with those left behind, thus tracing the circularity of exile and the continuing politics of return.

Comments from the Director: Tenzin Tsetan Choklay

Following the screening, Prof. Pan, Mei-Lin, who moderated the event, invited the film’s director, Tenzin Tsetan Choklay to provide his reflection about the filmmaking process. Before Tenzin’s intervention, Prof. Pan initiated the dialogue as she contextualized the film within her own ethnographic research on stateless Tibetans in India, noting the increasing trend of relocation of stateless Tibetan refugees from India to Europe and the United States. This movement, she observed, led to significant demographic change of Tibetans in India and across the world.

Tenzin started his intervention in this discussion by providing an autobiographical account of his trajectory. Tenzin was born in India, having lived across multiple countries, and is now based in the United States and India. He co-founded Drung, a collective that seeks to institutionalize a cinematic voice for Tibetans. The motivation for State of Statelessness, he explained, emerged from conversations with the late filmmaker Pema Tsedan, who expressed his and those in Tibet and their interest in the lives of Tibetans outside Tibet. Tenzin further emphasized that while much visual discourse on Tibet remains concentrated on political conflict between Tibet and China, this film seeks to move beyond the political discourse to articulate the subjective interiorities of stateless experiences of displaced Tibetans.

Discussants’ Interventions

The discussion featured two academic respondents, including Prof. Liu, Yu-Shan (Department of Southeast Asian Studies, National Chi Nan University) and Dr. Dolma Tsering (Postdoctoral Researcher, ICCS and the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Yang-Ming Chiao Tung University). Prof. Liu, whose research focuses on stateless Tibetans in India and France, commented on several aspects of the film. She touches on the significant demographic transformation and relocation of stateless Tibetan refugees from India to third countries such as France and other countries. This kind of onward migration, she observed, signals not merely economic migration but a quest for juridical recognition and existential security. Drawing on her ethnographic insights, Prof. Liu highlighted the paradox of onward migration; even after arriving in Europe, Tibetans must renegotiate belonging, learn new languages, and navigate bureaucratic and border regimes that temporarily suspend familial and social connections. Statelessness, she contended, persists as a lived condition beyond legal incorporation, manifesting in affective dislocation and social alienation.

Dr. Dolma Tsering, in her commentary, interrogated the terminological and epistemic implications of the term statelessness. She observed that scholarly and public discourse often substitutes “refugee” for “stateless,” thereby ignoring the precarious legal status of Tibetans in India. Dolma proposed the composite term “stateless refugees” to capture the legal and political duality: individuals displaced by political conditions and simultaneously excluded from formal state protection. Her intervention foregrounded the need for precision in conceptual vocabulary, as such terms frame the legitimacy of claims to rights, belonging, and representation.

Question and Answer Session

The question-and-answer session foregrounded several key theoretical questions. Prof. Pan raised the notion of a “global Tibetan,” probing whether transnational dispersal enables new forms of globalized identity or further entrenches fragmentation. Dolma queried the uncertain future of Tibetans in India in the post–Dalai Lama period, while Prof. Liu explored the intergenerational negotiation of cultural identity among the Tibetan diaspora. Prof. Joyce C. H. Liu commended the film for shifting the analytical gaze from victimhood to agency, emphasizing the importance of self-representation in decolonizing the narrative of Tibetan exile. She also asked about the darker side of statelessness, Tibetans, and their onward migration to third countries.

In response, Tenzin Tsetan Choklay reflected on the historical evolution of Tibetan statelessness. The first generation of stateless Tibetan refugees, he noted, regarded statelessness as transitory, animated by the hope of return to Tibet soon. However, as the decades passed and subsequent generations were born in exile, statelessness became an enduring structural reality, shaping the life trajectories of younger generations. For younger Tibetans, citizenship and onward migration to a third country has become the new idiom of security and self-determination for themselves and their kids.

For Professor Liu's question about the future generation, despite these challenges, Tenzin expressed optimism regarding the Tibetan diaspora’s resilience. He attributed this to the elder generation’s insistence on cultural and political consciousness, which has sustained the community’s cohesion and identity.

Addressing the question of a post-Dalai Lama future, Tenzin acknowledged the uncertainty about the precarious legal status of Tibetans in India, given that much of the support Tibetans have received has a significant influence of His Holiness’s moral and political influence. The post-Dalai Lama period, he remarked, will likely be a time of uncertainty, testing the institutional and communal infrastructure of Tibetan exile.

In response to Professor Joyce Liu’s point, Tenzin agreed that the film sought to contest the stereotypical presentation of Tibetans, which is often portrayed as either a spiritual utopia or a humanitarian tragedy. Instead, State of Statelessness focuses on agency and representation, inviting audiences to see Tibetans not as static symbols but as historical actors shaping their own narratives.

In the final exchange, Dr. Dolma Tsering reflected on her research with Tibetan communities in Taiwan, observing that nearly ninety percent of second-generation Tibetans have lost proficiency in the Tibetan language, signaling an accelerated process of cultural assimilation. Tenzin responded that similar patterns prevail across Europe and North America, underscoring the urgent necessity of cultural preservation through creative media. He described State of Statelessness as part of an emerging cinematic archive of Tibetan diaspora life, one that resists erasure and reclaims the authority to narrate Tibetan experience.

Conclusion

The screening and discussion of State of Statelessness demonstrated how cinema can operate as a decolonial and epistemic space, enabling stateless subjects to articulate their own histories and affective worlds. The event foregrounded critical debates on citizenship, identity, and belonging, while situating Tibetan statelessness within the broader discourse of global displacement. Ultimately, the film and subsequent discussion underscored that statelessness is not merely a legal absence of nationality, but a profound existential condition, one that continuously reshapes notions of home, kinship, and collective memory across generations and geographies.

近期新聞 Recent News