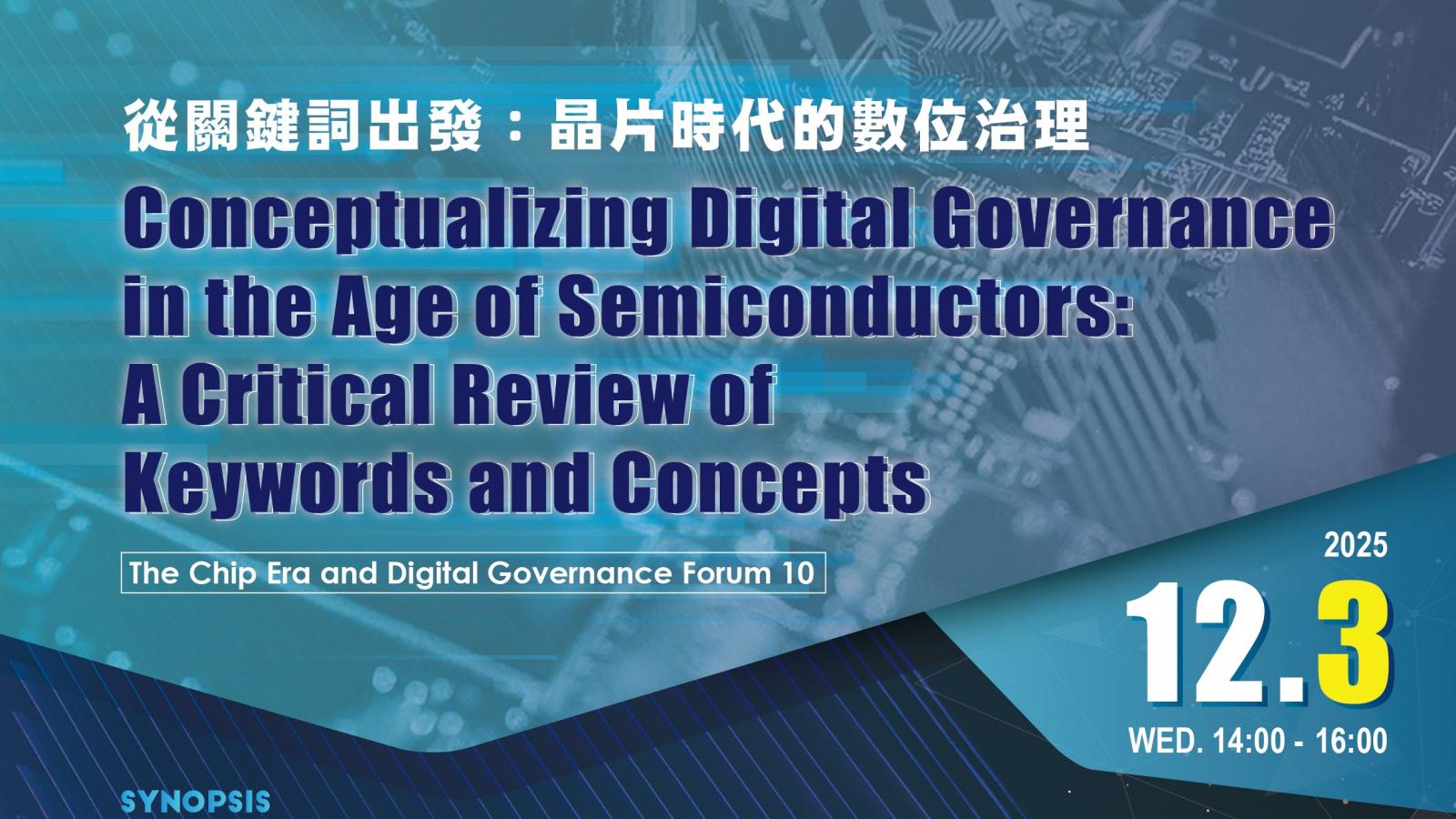

側記|從關鍵詞出發:晶片時代的數位治理

2025-12-03

Date: December 3, 2025

Time: 14:00-16:00

Format: Online (Zoom)

Organizer: International Center for Cultural Studies (ICCS), National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University

Author: Monika Verma (Myanmar Studies Center, Department of Asian Studies, Palacký University Olomouc, Czech Republic); contact: moniletit@gmail.com

Event Info: LINK

Photos: LINK

SUB-PROJECT|Subproject II: The Chip Era and Digital Governance (Principal Investigator: Joyce C.H. Liu)

This forum critically examined keywords and concepts related to digital governance, surveillance systems, and citizenship politics during the chip era. Three speakers presented case studies from China, the Tibetan diaspora in Taiwan, and Rohingya refugees in India, revealing how digital surveillance technologies reshape power relations across Asian contexts. The presentations explored distinct yet interconnected dimensions of digital governance: surveillance capitalism as a state-corporate nexus in China, societies of control operating through platforms like WeChat, and the paradoxes of digital identification systems for stateless populations.

Tzu-kai Liu: Surveillance Capitalism and Digital Governance in China

Assistant Professor, Department of Ethnology, National Chengchi University

Liu opened the forum by analyzing surveillance capitalism in the Chinese context, arguing that China's model diverges significantly from Western surveillance capitalism. Drawing on Shoshana Zuboff's work, he explained how tech companies monetize behavioral data, but China presents a distinctive state-corporate nexus where surveillance serves state purposes rather than purely commercial interests. Liu introduced chips as critical infrastructure for digital governance in China, strategically significant for both state control and economic competition amid US-China technological tensions. China has been developing domestic AI chip industries like Huawei while mandating domestic chips in critical infrastructures—not merely for economic advancement but for creating ‘governable subjects’ through digital infrastructure. The presentation explored China's unique state-corporate surveillance arrangement. Unlike Western models where private corporations lead data collection, China integrates data collection directly into state governance. Tech corporations function as part of a state-corporate nexus, with platforms like WeChat and Alipay serving both commercial and governmental monitoring purposes.

Liu introduced ‘grid-style governance,’ a pilot program spreading across Chinese cities. This system divides urban areas into smaller grid units, each assigned grid workers responsible for collecting information, handling incidents, and responding to service needs. During the pandemic, grid officials became ‘super task forces,’ enforcing quarantine measures and developing health code systems, intensifying grassroots governance through digital infrastructure. Liu argued that China's model represents ‘state surveillance capitalism’ producing ‘governing capital’ rather than commercial capital—data serves population management and social stability rather than advertising optimization. Chinese tech corporations support this system by building network infrastructure covering social communities, labor communities, and migrant management, fundamentally reshaping relationships between the state, technology, and citizens.

Dolma Tsering: Societies of Control - WeChat and the Tibetan Diaspora

Postdoctoral Fellow, International Center for Culture Studies, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University

Tsering examined how digital technologies reshape power through the Chinese government's control over Tibetans in Taiwan via WeChat. She began with a personal anecdote: joining the Tibetan community Line group in Taiwan in 2019, she found that despite 200 members, only two to five remained active. This silence, she argued, reveals how digital technologies reshape experiences of refugees and politically displaced populations. Tsering employed Gilles Deleuze's "societies of control" concept. Deleuze's 1992 essay identified a shift from disciplinary societies (enclosed institutions) to societies of control, where power operates through continuous, flexible control via electronic monitoring and digital networks. She outlined three characteristics: the shift from mold to modulation (continuous monitoring versus fixed spaces); control mechanisms changing from signatures to digital codes, transforming individuals into ‘dividuals’, information flows constantly monitored by algorithms; and voluntary participation creating paradoxes where freedom becomes a control mechanism.

WeChat, launched in 2011, evolved into a ‘super app’ performing functions beyond messaging. Chinese users spend one-third of mobile time on WeChat, accessing it ten-plus times daily. Critically, WeChat lacks end-to-end encryption, operates as closed-source, and doesn't guarantee data protection from government access. The platform employs sophisticated surveillance through real-time communication scanning for flagged keywords, instant censorship, and immediate authority alerts. Tsering shared case studies from Taiwan research. ‘Tenzin,’ who worked for the Central Tibetan Administration (labeled separatist by China), was blacklisted. When he reinstalled WeChat in Taiwan and called a friend, their conversation was cut after ten minutes, demonstrating real-time monitoring and immediate state intervention. ‘Hamo’ from Tibet Autonomous Region received a friend request from someone eventually offering travel permits and financial support for return. Her brother revealed that the Public Security Bureau had visited him, claiming Hamo suffered in Taiwan and requesting her WeChat contact, illustrating how regimes manipulate family emotions through digital platforms. A third group reported no direct threats but revealed normalization of self-censorship. As one stated: "As long as you do not engage in political activities, you have full freedom." Here, freedom becomes conditional access through political silence. Tsering concluded that in the digital age, the question shifts from "Are you being watched?" to "How do we manage our visibility?" Physical displacement no longer ensures sanctuary. What appears as freedom, staying connected with family, simultaneously becomes control. People adapt by censoring themselves, becoming silent participants in monitoring scenarios.

Monika Verma: Digital Governance and Rohingya Refugees

MSCA-CZ Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Myanmar Studies Center, Palacký University Olomouc, Czech Republic

Verma examined the intersection of technology, human rights, and exclusion through Rohingya refugees in India, arguing digital governance involves power, justice, and dignity questions. Digital systems promising inclusion can entrench discrimination without adequate safeguards. Digital governance, per Ben Williamson, involves moving services to digital formats allowing continuous data collection about citizens' everyday activities. This fundamentally transforms how states relate to and govern populations, creating ‘surveillance states.’ Verma mentioned UNHCR's PRIMES (Protection and Identity Management Ecosystem), launched in 2018 for better refugee data collection. However, she also identified that when power is skewed against refugees, digital platforms may not create co-shared value. Unlike Uber or Airbnb where both sides benefit, refugees cannot negotiate terms or refuse participation without losing essential services.

The presentation examined biometrics, measurable physical characteristics verifying identity. Verma emphasizes ‘docility of extraction’, where bodies become extractable data regardless of consent. Providing data becomes survival performance— what Engin Isin calls 'acts of citizenship.’ Refugees perform these not as citizens with rights, but because docility enables entitlements. This exemplifies what Mirca Madianou would call ‘technocolonialism’, digital developments reinforcing colonial dependency relationships. India presents a stark ‘legal paradox.’ Rohingyas are simultaneously UNHCR-recognized refugees yet state-categorized illegal migrants. They exist in a ‘double bind’: needing identification for services, needing legal status for identification, yet legal status remains contested, existing in limbo, suspended in permanent temporariness. Verma examined Aadhaar, India's biometric identification system enrolling 1.3 billion people. For Rohingyas, it functions as exclusion mechanism. Those with long-term visas could obtain Aadhaar, but once recategorized as illegal migrants, became ineligible. Yet their data remained with the state. Possessing Aadhaar led to criminalization: fraudulent document charges, detention, fines. The state demands identification for services yet criminalizes its creation by those labeled illegal.

Despite constraints, Verma documented remarkable digital agency. In Bangladesh camps with internet restrictions, Rohingyas developed ‘parallel internets’ using tea shops to transfer content, building underground informal networks. In Indian cities, young Rohingyas use digital platforms countering negative narratives, enabling future mobility through Google Translate for language learning, subtitled content for English acquisition, and online tutorials for computer skills. Verma concluded that digitalization isn't a panacea, technology alone cannot solve refugee protection. Governance of marginalized populations involves political power and administrative technology interaction. Administrative technology executes politics. Without changing exclusion mandates, digital systems execute structural discrimination more efficiently. Technology amplifies political will, if exclusionary, technology becomes its instrument.

Discussion

Following presentations, Professor Joyce C. H. Liu posed questions about surveillance capitalism affecting cross-border movement, whether Tsering would expand research beyond Taiwan, and whether concepts apply to Indian refugee groups. Additional questions addressed Chinese youth rendered ‘homeless’ by social credit systems and India's compulsory mobile app requirement. Liu clarified that grid-style governance monitors migration through human and digital processing, with rewards and control coexisting. Regarding social credit, he noted unemployment stems from economic slowdown, not social credit scores. Social credit systems exist but don't function well in most areas; localized grid systems function most effectively. Criminal records, not social credit scores, determine access. Social credit increasingly serves corporate purposes rather than comprehensive authoritarian control. Tsering confirmed completing transnational research comparing Tibetans in Taiwan, Switzerland, and India, with forthcoming publication on Chinese government repressions via WeChat. She elaborated on Tibetan self-protection strategies: using two phones (one exclusively for WeChat, kept at home), engaging in mundane conversations, using poetic or satirical language. After a flood, one person's brother posted "nothing is safe here, please don't contact" poetically rather than directly. Verma addressed India's surveillance technologies remaining in early trial stages versus full implementation. She described how Rohingya data collection in Jammu caused fear, with information spreading quickly through digital networks. This represents ‘strategic visibility and selective invisibility’, choosing visibility with NGOs advocating rights versus invisibility with state authorities.

Conclusion

The forum illuminated how digital governance operates across diverse Asian contexts, revealing common patterns. Digital governance is fundamentally political, technologies execute political agendas rather than operating neutrally. Marginalized populations experience digital governance as compulsory; biometric enrollment and platform participation become survival performances. Despite asymmetric power, people exercise agency. Chinese migrant workers use multiple phones strategically; Tibetans employ dual phones, self-censorship, and poetic language; Rohingyas build parallel infrastructures and practice strategic visibility. Digital infrastructures reshape citizenship and belonging, redefining who counts as citizens, who deserves protection, who can be excluded. The forum emphasized transcending complex clusters of discourse, attitude, and border politics in digital governance. As technologies evolve during the chip era, critical engagement with surveillance capitalism, societies of control, technocolonialism, and data justice becomes vital for understanding and resisting digital infrastructures' transformation into exclusion and inequality instruments.

近期新聞 Recent News