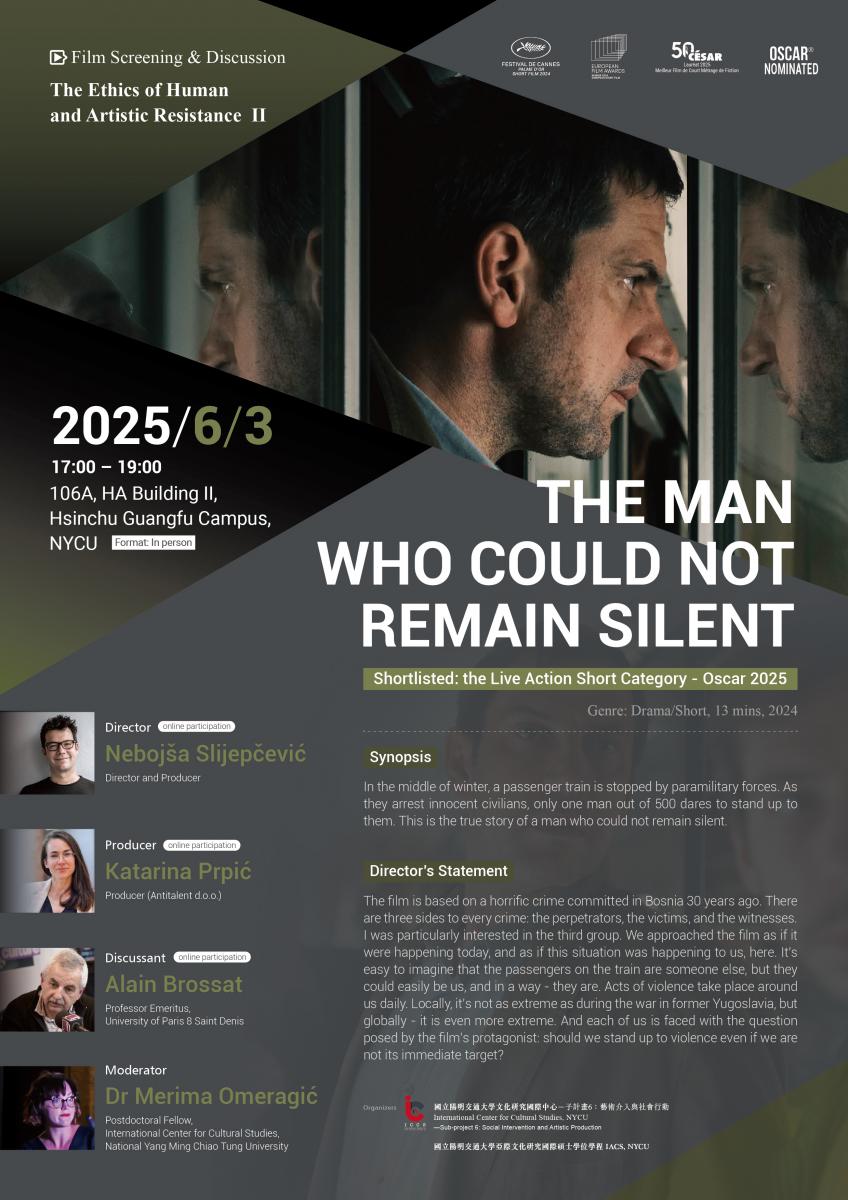

側記|Film Screening & Discussion|The Ethics of Human and Artistic Resistance II: THE MAN WHO COULD NOT REMAIN SILENT

2025-06-03

Topic|Film Screening & Discussion|The Ethics of Human and Artistic Resistance II: THE MAN WHO COULD NOT REMAIN SILENT

Time|2025/6/3 5PM

Venue|106A, HA Building II, Hsinchu Guangfu Campus, NYCU

Director|Nebojša Sljepčević (online participation)

Producer|Katarina Prpić (online participation)

Discussant|Alain Brossat, Professor Emeritus, University of Paris 8 Saint Denis (online participation)

Moderator|Dr Merima Omeragić, Postdoctoral Fellow, International Center for Cultural Studies, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University

Event Info|LINK

Event Photo|LINK

Event Recording|LINK

Reported by|Dr Merima Omeragić

Sub-project|Social Intervention and Artistic Production

Convener|Wen-Shu Lai

As part of the ongoing academic series The Ethics of Human and Artistic Resistance II, a screening of The Man Who Could Not Remain Silent (2024), directed by Nebojša Slijepčević, was held on May 26, 2025. This session marked the second installment in the series, which focuses on the ethics of resistance as portrayed through film, with an emphasis on the historical and geopolitical contexts of World War II, and the war disolution of Yugoslavia, while drawing connections to contemporary global conflicts.

The event commenced with an introduction by Dr. Merima Omeragić, who contextualized the film within the broader framework of the series and emphasized the importance of art in confronting war, violence, and historical memory. She underlined the continuity of armed conflicts globally—visible and invisible—and invited participants to consider cinema’s ethical and aesthetic capacities in response to contemporary crises.

Following the screening, a discussion was held with director Nebojša Slijepčević and producer Katarina Prpić, who elaborated on the production process and artistic choices. Subsequently, Professor Alain Brossat offered a philosophical interpretation of the film’s themes, particularly the dynamics of resistance, witnessing, and the role of the spectator. The session concluded with an open discussion, during which participants shared reflections on the film’s impact, its ethical provocations, and its relevance to ongoing conflicts in regions such as Palestine and Ukraine.

The post-screening conversation was opened by Dr. Merima Omeragić, who emphasized the intense viewer identification the film invites—not only with the potential victim but also with the moral question confronting each bystander: to act or remain silent. Dr. Omeragić highlighted the film’s ability to evoke both pride and shame, framing it as a cinematic confrontation with the ethics of complicity and courage.

In response, director Nebojša Slijepčević elaborated on the creative and ethical considerations that informed his storytelling. Notably, he explained his decision to construct the narrative not from the perspective of the heroic figure, Tomo Buzov, but rather from that of a silent bystander—a man who witnesses injustice but ultimately fails to act. Slijepčević described this choice as both an artistic and ethical strategy, aiming to produce deeper viewer self-reflection. He emphasized that crafting a hero’s internal motivation would have been speculative and possibly sentimental. Instead, focusing on a morally conflicted witness allowed the film to explore fear, complicity, and the emotional paralysis of ordinary individuals. By casting well-known actor Goran Bogdan—who visually embodies conventional heroism—the film deliberately misleads the audience into assuming he is the titular hero. This deliberate misdirection serves to challenge viewers' expectations and to provoke critical introspection regarding their own moral positioning in the face of violence.

Slijepčević shared that this narrative choice emerged during his research process, which involved grappling with the historical complexities of the original event, selective inclusion of material, and a commitment to making the story resonate with present-day audiences. He affirmed that the project was not only a film about a past event, but an invitation for viewers to reconsider their responsibilities in a world still saturated with violence and conflict. Following the screening, director Nebojša Slijepčević shared insights into the ethical and creative challenges of making The Man Who Could Not Remain Silent. He emphasized the film’s central moral question: the choice between silent complicity and courageous resistance. Intentionally avoiding a heroic perspective, he focused on the bystander—a character viewers could more realistically identify with—to provoke reflection on personal responsibility in the face of injustice. Slijepčević highlighted the ethical responsibility of portraying real events. Before writing the script, he contacted the son of Tomo Buzov to request permission to use his father’s name and story. The director also conducted extensive research, consulting hundreds of pages of testimonies. While all characters, with the exception of the one based on Buzov, are fictional, their words were often drawn directly from documented witness accounts. The film, he noted, is not a reconstruction but a fictional narrative rooted in truth. Its positive reception by victims’ families and former passengers affirmed its ethical and emotional authenticity.

Following the director's response, Dr. Merima Omeragić invited producer Katarina Prpić to reflect on how she became involved in the project and the challenges she faced in shaping the film from idea to production. She also asked how the historical figure of Tomo Buzov and the film were initially received in Croatia.

Prpić shared that she and her production partner first encountered the story through a newspaper article questioning why Buzov’s courageous act had been largely forgotten. They saw the event’s immediacy and emotional power as ideal for a short film—self-contained, urgent, and impactful without need for additional narrative framing. After watching Srbenka, the film by Nebojša Slijepčević, they approached to him, and Slijepčević embraced the idea. Together, they chose a fictionalized, cinematic approach rather than a reconstruction, taking time to carefully consider narrative, tone, and ethical implications.

As producers, they aimed to give the short film unusually high production value. This required extensive coordination and two years of fundraising, resulting in a co-production between Croatia, Bulgaria, France, and Slovenia. Beyond logistics, the team remained attentive to every step—securing permissions from Buzov’s family, guiding casting, and shaping the film’s integrity. Regarding public reception in Croatia, Prpić noted that while the film received wide acclaim, it also reopened important conversations around national memory, forgotten acts of resistance, and the ethics of commemoration in post-war societies.

Prpić noted that the first support came from the Croatian Audiovisual Center, which funded the project after reading the script. Following Cannes, the team chose to screen the film widely across Croatia—without a restrictive festival strategy—offering it free of charge to any cinema or festival interested. The reaction was overwhelmingly positive. She highlighted that the film avoids nationalistic framing, focusing instead on human fear and moral hesitation, which allowed for broader empathy and engagement. Addressing moderator’s second question, the producer explained that the team identified countries with funding mechanisms for short film co-productions. Though initially rejected by Denmark and Bulgaria, they later secured support from Bulgaria, France, and Slovenia. French producers contributed CNC slate funding, which became a turning point, enabling production. The crew was international—DOP from Slovenia, production designer and editor from Croatia, sound from Bulgaria—making it a truly collaborative Balkan-European effort.

Dr. Merima Omeragić asked Katarina Prpić how co-productions help filmmakers from small countries like Croatia and others in the former Yugoslavia, where public film funding is often unstable. She referenced recent struggles of prominent directors, including Bosnia’s Jasmila Žbanić, as an example of broader funding difficulties. The producer emphasized that while funding is always a challenge—especially in small and post-conflict countries—the strength of the project itself is crucial. In Croatia, unlike in some neighboring states, there is relative stability with public film funds, making planning possible. However, when competing for international funds, especially in larger countries like France, the competition intensifies. She stressed that producers need to be realistic, understand each fund’s criteria, and know the landscape to succeed. Even when funding isn’t secured, the feedback can be valuable for improving a project. In the case of The Man Who Could Not Remain Silent, it was the strength of the story and Nebojša’s vision that attracted a French co-producer willing to invest private slate money. Without a compelling story, none of the funding efforts would have worked. Strategic yet realistic planning, she concluded, is key to managing expectations and maintaining team morale during long funding processes.

Dr. Merima Omeragić asked Professor Alain Brossat, the discussant, to reflect on The Man Who Could Not Remain Silent within the context of contemporary global conflict, highlighting her concern over the rise of violence and erosion of human values. She invited him to share his impressions of the film, particularly in light of his engagement with ethics and aesthetics.

Professor Brossat responded by focusing on the film’s unique narrative angle: it centers not on the hero, Too Buzov, but on an ordinary man—frightened, passive, and ultimately complicit. While the hero briefly confronts the oppressor and disappears from the screen, it is the average man’s gaze, fear, and moral collapse that guide the audience through the film. He noted that the hero resists not out of religious or ethnic identity, but from a universal humanist principle—evoking Yugoslav socialist ideals. The protagonist, by contrast, submits under pressure, choosing silence and safety over resistance. Professor Brossat emphasized the film’s powerful suggestion: the hero is an exception, while the ordinary man—representing most of us—is the rule. His survival comes at the cost of shame and self-contempt. He concluded by noting the film's clever narrative structure, distinguishing the "hero" from the "protagonist" and challenging the viewer to confront their own position in the face of violence and injustice.

Professor Alain Brossat offered a philosophical reading of the film, emphasizing that its focus is not on a heroic figure, but on the ordinary man who fails to act against injustice. The film, he argued, portrays indecision as a key moral and political theme — reflecting how most people, when faced with terror, comply rather than resist. This shift from heroism to hesitation gives the film its universal power, resonating beyond its Bosnian context. Brossat connected the film to the idea of the “grey zone” — the moral ambiguity that defines everyday behavior under oppressive systems. He compared it to Marcel Ophuls’ documentary The Sorrow and the Pity, which challenged myths of widespread resistance during WWII in France.

Moderator Omeragić thanked Professor Brossat and highlighted the film’s achievement in transforming a specific historical moment into a universal artistic message. She then asked director Nebojša Slijepčević to elaborate on the role of ethics in his creative process. He reflected on the moral responsibility behind representing war trauma, particularly as a Croatian director depicting Serbs as oppressors and Bosniak Muslims as victims. Slijepčević emphasized the need to ask: Why am I making this film, and, what gives me the right? He acknowledged the sensitive regional context where film has often served nationalist propaganda. He justified his choice through the story’s universal relevance, noting parallels with global conflicts and the ongoing need for individual moral action. To further avoid nationalist bias, he intentionally cast actors across ethnic lines, creating a symbolic melting pot within the train setting — underscoring the film’s message of shared human responsibility beyond ethnicity.

Moderator highlighted the film’s major international recognition, including a Palme d'Or, a César Award, a European Film Award, and an Oscar nomination. She asked producer Katarina Prpić about the impact of such accolades on the film’s future. The producer clarified that the film was nominated—though not awarded—an Oscar, and emphasized how these honors significantly broadened the film’s reach. With over 130 global festival screenings and theatrical and television distribution in both the U.S. and Europe, the awards helped secure rare and valuable slots for short films, ensuring a continued and expanded audience.

Dr Omeragić invited Professor Brossat to expand on the ethical dimensions of art and its societal role, asking whether films should be viewed as personal experiences or as vehicles for broader social and philosophical reflection. Professor Brossat responded by emphasizing the film’s power to raise crucial ethical questions, particularly: Can we expect extraordinary actions from ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances? He stressed that this question is deeply relevant today, citing Gaza as a current example of a moral test for ordinary individuals. He also highlighted the film’s insight into the concept of the “ordinary perpetrator”—individuals who commit atrocities while appearing as normal, obedient soldiers. This camouflage of violence behind the mask of order and legitimacy, he argued, helps explain the obedience and passive complicity of ordinary people in the face of brutality.

In the open discussion, Professor Joyce Liu praised the film for its masterful handling of tension without graphic violence, highlighting the constant threat of arbitrary power and lawlessness. She connected the film’s themes to real-world parallels, including the oppression of Uyghurs in China, Tibetans, Rohingya, Muslims in India, and political repression in Hong Kong. Professor Liu emphasized how the film universalizes fear, insecurity, and moral conflict under authoritarian conditions, making it globally resonant.

Moderator acknowledged this transnational reception, noting how audiences across continents can identify with the characters, particularly through the emotional tension and moral ambiguity embodied by the protagonist. She emphasized the film’s capacity to provoke self-reflection in viewers. A participant then raised concern about the underrepresentation of African suffering in global cinema, urging for stories from conflict zones like Ethiopia and the DRC to be brought forward. In response, Professor Brossat agreed, lamenting the stark imbalance in global film production and access, noting that African stories are often invisible due to systemic underfunding and dependency on European co-productions. He affirmed the need for greater visibility of African filmmakers and narratives in global discourse.

In concluding remarks, Dr. Omeragić invited reflections from the director and producer. Director Nebojša Slijepčević emphasized the significance of local storytelling in small national cinemas like Croatia’s. He stressed that films must first address local audiences and issues that larger industries would overlook. While acknowledging the challenges African filmmakers face, he underlined that even within Europe, filmmakers from smaller nations struggle with visibility and funding. He shared that his true aim was not international acclaim but regional dialogue—pointing to the film’s screening in Belgrade as a landmark moment of cross-national recognition and healing, particularly given the film’s focus on a Serbian war crime portrayed by a Croatian team.

Moderator echoed the earlier concern about global inequalities in cultural production, acknowledging that African and other marginalized communities often lack platforms despite rich artistic traditions and pressing stories. However, she also drew attention to the global scale of atrocity and the ethical imperative of conscience: from Rwanda (1994) and Srebrenica (1995), to Palestine and the Rohingya today. Films like The Man Who Could Not Remain Silent, she argued, are vital not only for their political relevance but for their role in cultivating human solidarity and confronting vulnerability in the face of violence.

In closing, producer Katarina Prpić reflected on the earlier question regarding African cinema, acknowledging the significant structural barriers while also highlighting pathways for opportunity. Drawing on industry experience, she emphasized that while many African filmmakers face severe production constraints, international co-productions—particularly with European partners—have made impactful stories possible. Citing examples like Village Next to Paradise, she encouraged aspiring African storytellers to craft compelling pitches and seek global platforms, as Western audiences often remain receptive to narratives from culturally distinct contexts. Prpić affirmed the importance of local storytelling, echoing the director’s earlier point, but added that transnational collaboration is increasingly feasible and necessary. She concluded by thanking the moderator and panel for fostering a rich, globally-minded discussion on storytelling, production, and representation.

Dr. Merima Omeragić closed the session by thanking all the participants, particularly Nebojša Slijepčević and Katarina Prpić, for their insightful and artistic contributions. She also thanked Professor Alain Brossat for his powerful analysis of the film. She stressed the relevance of integrating art into academic and pedagogical contexts, underscoring how films like The Man Who Could Not Remain Silent open critical avenues for exploring ethics, memory, and transnational solidarity. Her final remarks honored the diverse perspectives—European, Asian, and African—that shaped the dialogue, affirming the session as a meaningful moment of shared reflection and cultural exchange.

近期新聞 Recent News